Ah, 1979: the year the Shah said ‘adios’ to the land of the Lion and Sun; the year Ayatollah Khomeini returned from exile in Fgghhhance to declare the establishment of the Islamic Republic; the year my parents got married (well, they tied the knot on New Year’s Eve in 1978, but you get my drift) and managed to find a flight out of Iran back to the States; and, the year the world was given its first dose of TVAT. It’s pronounced ‘tee-vat’, to be precise – not ‘tvaht’, and certainly not ‘twat’, as she’s quick to point out. It’s what Taravat Talepasand signs as, and we wouldn’t have it any other way; and, while I may have coined the term ‘Sex, Drugs, and Gol-o-Bolbol‘ that all of we cats at REORIENT swear by, Taravat – who just enjoyed a smashing exhibition of her new series of works at San Francisco’s Guerrero Gallery – was its living, breathing, rock and rolling embodiment, long before I came around. All hail TVAT.

‘Made in Iran, born in America’ – that’s been your motto for quite some time now. How has Iran made you, despite having lived almost all of your life in the States?

I have been harassed almost all of my life for not being Iranian, as I wasn’t born in Iran. This surprised me, since as a child I had resented being Iranian only because I was growing up in a predominantly white, Republican, suburban, racist town in Portland. Never did I think I wasn’t Iranian; when you stepped inside my house, there was a constant smell of sabzi and fresh tea (smuggled from Esfahan) that was always brewing, and the sounds of Googoosh and Ebi.

Iran has shaped who I am, as a human being and particularly as a woman, since I did not want to live in post-Revolution Iran, just like my mother and other female relatives didn’t. Literally, I was made in Iran, as I was conceived in Esfahan, and was born in America in 1979, the year that marked the formation of the Islamic Republic. My parents and family in Esfahan have shaped me, but it was my own decision to embrace my heritage and give respect to a country that is full of the most inspirational art, culture, food, music, and language, which have all informed my work and allowed me to embrace the outer skin and inner fire defining me as an Iranian-American.

There have been many who have ridiculed me and doubted my heritage, but my blood and family define me, and nobody can take them away from me. Whether you are born in Iran or a part of the Iranian diaspora, you are whatever you choose to define yourself as. So, to whoever is reading this: know that I define myself as an Iranian-American proud to have Muslim blood flowing through her veins, and who is a woman proclaiming her own freedom regardless of where her body is. By the way – I do hold an Iranian passport and social security card, since the government defines me as an Iranian by way of my family in Iran.

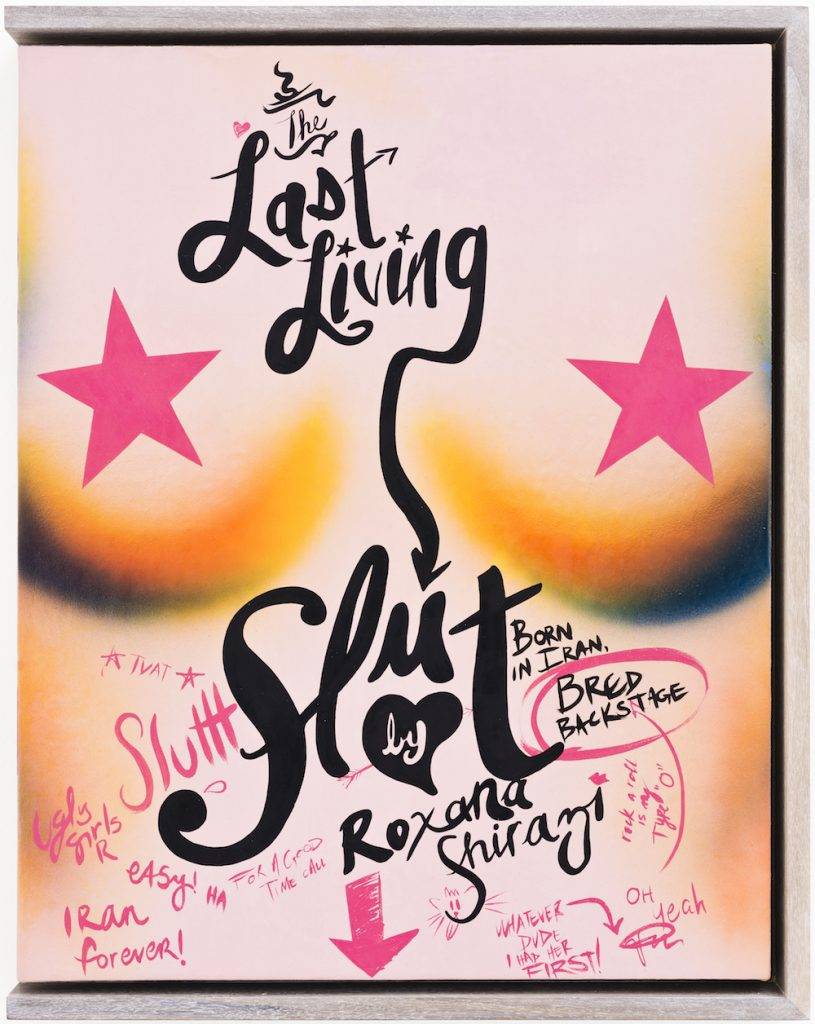

You weren’t bred backstage, though, like Roxana Shirazi, the ‘last living slut’ …

Not at all. I was ‘bred’ in various ways by means of travelling the world and experiencing different cultures with my own freedom of choice – a luxury I am grateful for, since I know that it’s not something everyone has. Roxana Shirazi is a writer born in Iran and raised in London, and describes ‘bred backstage’ in a way people might interpret as blasphemous. She has been an inspiration of mine for several years, for many reasons. One is that she reminds me of my older sister, who introduced me to Led Zeppelin, Metallica, Guns ‘n’ Roses, and Nirvana … My badass sister I looked up to, who had boyfriends when she wasn’t allowed to, who went to concerts and parties, and who witnessed her friends using drugs: all things my parents despised and punished her for, but that I took note of and filtered into my work decades later. I see Roxana in the same way as my sister: an inspirational woman holding power to do whatever the fuck she wants, and doing it as a proud Iranian born in Iran – something I can never say I am.

Welcome to the club. In a story in my upcoming book, I wrote something along the lines of, ‘I’ll never have the honour of calling myself an Iranian – born and bred’. Anyway … to reference an earlier series of yours – and, to quote Ahmad Fardid and Jalal Al-e Ahmad – do you feel like you’ve become ‘Westoxicated’? Do you wish, for instance, that you’d at least grown up in Iran? I sometimes think I missed out on a lot of things.

Absolutely. The idea of the ‘Westoxification’ was first introduced to me by Azadeh Moaveni in her book Lipstick Jihad. She’s such a powerful writer, and has inspired me to embrace my ‘otherness’ growing up Iranian in America and being American in Iran – in other words, my tangled identity as an Iranian-American. I have no regrets. Never did I think it would have been better to be raised in Iran like my sister until I was harassed and ridiculed by young Iranians for being ‘less’ Iranian because I was born in America. I’m grateful, in fact. I am one hundred percent proud of my upbringing and grateful to my mother to have forced my father to stay illegally in America.

I was fortunate enough to visit Iran during my summer breaks from school and experience myself as an American and Iran, and return to feeling Iranian in America. Bouncing back and forth between two countries wasn’t a conflict for me, but rather an inspiration to create work embracing the similarities and realities between East and West.

Do you think living in the States during an era in which Iran has been so vilified and maligned has actually helped foster a love for your homeland?

Not right away. I remember my mother asking me to tell people that I was from Iraq during the Iran-Iraq War. I remember feeling ashamed and confused about having to lie about where my family was from, but soon learned that it was to protect myself from being bullied, beaten up, and even raped. There were a lot of terrifying experiences I blocked out as a child during the eighties, during the War and the era of Not Without My Daughter. It was a time when my friends’ parents would not allow them to visit me at my house, or partake in Norooz celebrations.

The only backlash has been from arrogant, self-righteous, narcissistic Iranians who believe I’m less Iranian because I wasn’t born in Iran. Fuck off.

Growing up afraid and ashamed of one’s heritage and homeland is a terrible thing that no child should experience. Almost three decades later, I have found myself focusing on something I was grown to deny because of conflict and Western media. No more. I love Iran – not necessarily the government, but the country and its culture.

Right. Now, to take things to a higher level – since we collaborated on our ‘Sex, Drugs, and Gol-o-Bolbol’ totes, you seem to have taken the concept even further: bongs, ‘opium tears’, acid and naked women on Iranian banknotes … What’s going on?

Oh, I’ll tell you what’s going on: a contemporary Iran devoid of sex, drugs, and the Westoxification that Iranians have longed to embrace. Drug use in Iran is a historical phenomenon: opium has an ancient role in Iranian history, and hash is an indigenous drug. In Iran, they call it shahdaneh, meaning ‘kingly seed’. Historically, Iranians smoked hashish, not weed. However, during the last ten years, weed has become extremely popular, like in the States. The use of hash oil in my works links the past and present, and this is also why I paint with egg tempera.

Whoa.

The use of drugs in my work is meant to show that they are widely available and used in the twenty-first century. Acid offers a tint, hue, and texture that can’t be detected by our eyes. Having a hit of LSD on Iranian currency gives back its value in the States, and probably more, were it to cross borders. Putting LSD on a country’s currency implies that one doesn’t only have the power to recreate a country’s image – to own it in some way – but to also consume it (adding insult to injury) and get high off of it. You see, for me, there’s so much more than just the act of painting and creating art … I seek to find challenges in my work through the meaning of materials, which create their own balance of good and evil.

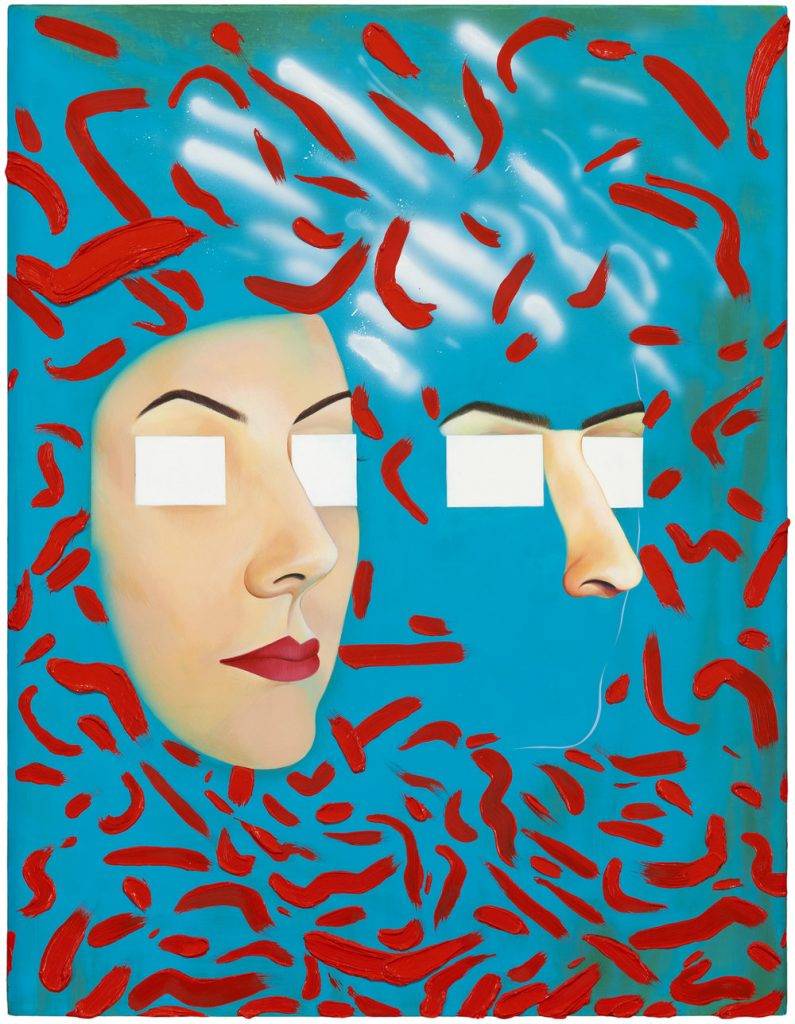

While researching my own fascination around opium use in Iran, I started making clear and precise theoretical connections between opium in Persian miniature paintings and its control and deterioration of man as seen in my painting Andarooni, Birooni, Lies and Man. The opium flowers break through the cleric’s bust, uplifting his turban. I redefined the opium flower as a source of power, representing it as the femininity of Iran, which was once historically depicted as the rising sun. The female sun can particularly be found in artwork from the Qajar era. I proclaim the opium flower in place of Iranian women, breaking codes written by theologians.

Tell me more about LSD.

LSD is a drug offering a heightened spiritual experience often accompanied by feelings of a loss of identity, ego, and relationship to the exterior world. It holds the possibility of reconfiguring the structures of gender norms that dominate Islamic societies into a more open and fluid field of relations. One could eat the banknote and trip; but my trip is in the allegorical layers between currency, religion, female empowerment, and illegal drugs that all uphold strict codes around the globe.

Have you ever had a … hit? I think it would make me sick. If I had to choose, I’d go for opium. You know, to get that Sadegh Hedayat kind of high that also comes with a lovely scent. The Persian drug par excellence.

My interests aren’t to sensationalise artwork with illegal drugs, but rather to use the shared addictions of substances that are found between two opposing countries. I am not candy-flipping in Iran or America; I am an artist who decided to use an illegal substance as a painting medium to give meaning to the content of which I paint – something that can easily be taken out of context given the viewer’s own morals. I honestly haven’t tried LSD in my life!

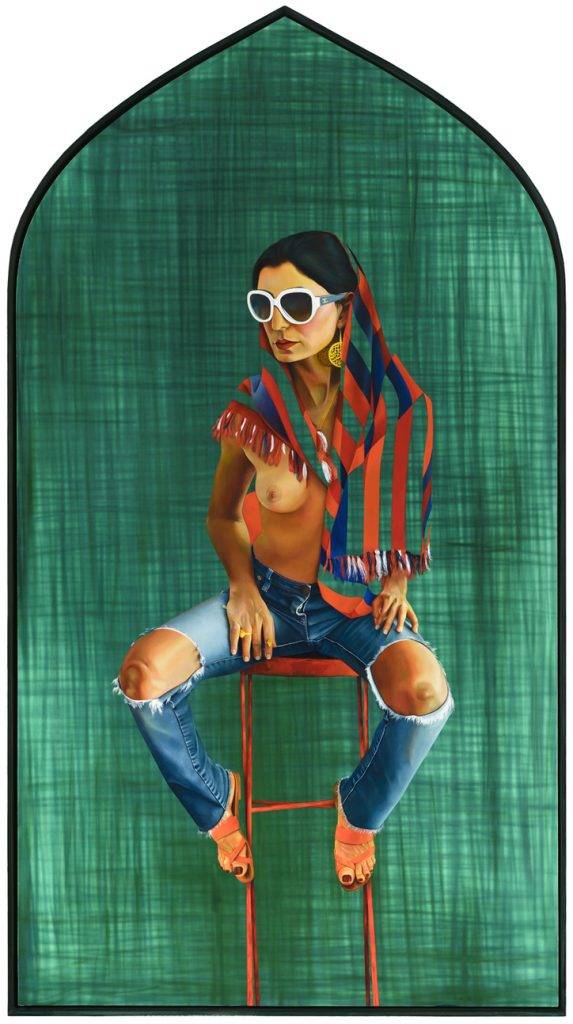

… And the naked women?

Sexually available and confident, the naked woman represents the fetishised body that forms the opposite side of representational politics in Iran. Iranian women and their bodies have become surfaces upon which political, economic, religious, and social antagonisms have fomented. Women in Iran are second-class citizens suffering from systematic disadvantages, structural inequalities, and institutional injustices promoted by forms of religious essentialism in a male-dominated society.

What I really like about this series of yours is that the name ‘Iran’ is so in-your-face. Too many Iranians I know, especially in the States, prefer to call their country ‘Persia’ – despite ‘Iran’ (lit. ‘Land of the Aryans’) being the indigenous name of the land since time immemorial. I think it’s reflective of shame and some sort of inferiority complex … You don’t see too many people emblazoning the name ‘Iran’ on denim jackets these days!

I do not define myself as ‘Persian’, although I could, since my heritage is rooted so far back in Esfahan. However, my decision to use ‘Iran’ on a denim jacket comes from wanting to embrace and proclaim the country I define myself to be from – not the old country of Persia, but pre-Islamic Republic Iran: Iran and only Iran, without its religious ball-and-chain. It’s true that it may be hard to find any fashionable attire with the name ‘Iran’ written on it in bold Latin letters, but if Kanye West can create a frenzy of coveted threads with the name ‘Pablo’ four times over – whether he’s referencing Pablo Escobar or the misogynist artist Pablo Picasso – then …

Shame comes from within, and is a self-defined, negative waste of time. I imagine this jacket to be worn and adored by those who have embraced their Iranian side. Since making this jacket and sharing it on social media, I’ve found so much love and support, as well as a community that understands my ambiguity between two opposing cultures. It’s as if this jacket belongs to a group in the Iranian diaspora that never felt it belonged to an Iranian community, but finds ‘weight’ in something that is as light as a feather and stiff as Iran. It’s one of the works I’m most proud of.

Have you received any recent backlash for your love of Iran?

Like I said before, the only backlash has been from arrogant, self-righteous, narcissistic Iranians who believe I’m less Iranian because I wasn’t born in Iran. Fuck off. Take your definition of ‘Orientalism’, which I find offensive, and see if you can create art that is as conceptually profound and technically on-point as mine. I am here to make Iran in vogue, and I think I have, along with you, Joobin, and Hushidar Mortezaie.

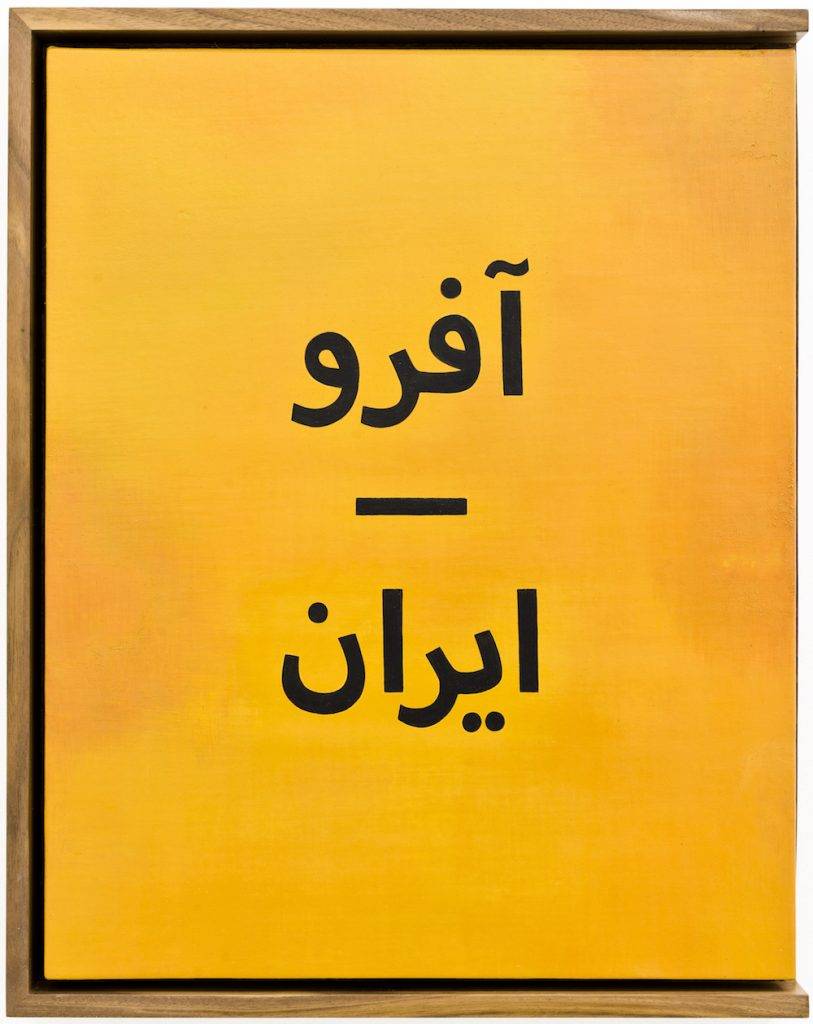

Strangely enough, we’re in this exhibition together. What’s a painting of Mahdi Ehsaei’s Afro-Iran doing there? I wrote an introduction to it two years ago.

I absolutely love this book. In fact, when you and Mahdi published Afro-Iran, I told my dear friend Jenna Wortham, who writes for the New York Times, about it, and she immediately purchased it. I had already bought two. This book tells of a community that so many Iranians don’t even know about, and describes a beauty belonging to itself. My decision to literally paint this book was to put a focus on Iranian writers living outside of Iran, in a diaspora that helps highlight various sides of Iran.

I didn’t change a thing about the book in my painting; but the secret challenge for me was to break the rule I’d created so long ago: to never paint in Persian. Why? I speak the language, but for now cannot read or write it properly. There is so much inspiration in this book, beside the photographs and the words so eloquently written by you. I was drawn to this book, which reads from left-to-right for Westerners and right-to-left for Easterners. The combination of both English and Persian struck my soul, as I was identified in a way in which I see myself, and that perhaps many other Iranians do, too.

Complete this sentence: if Taravat Talepasand is ‘TVAT’ and Hushidar Mortezaie is ‘Hushi’, then it must follow that Joobin Bekhrad is _______

RAD!

‘Made in Iran, Born in America’ ran between April 15 and May 6, 2017 at San Francisco’s Guerrero Gallery.

Originally published on REORIENT