The Trump administration is holding talks on providing nuclear technology to Saudi Arabia — a move that critics say could upend decades of U.S. policy and lead to an arms race in the Middle East.

The Saudi government wants nuclear power to free up more oil for export, but current and former American officials suspect the country’s leaders also want to keep up with the enrichment capabilities of their rival, Iran.

Saudi Arabia needs approval from the U.S. in order to receive sensitive American technology. Past negotiations broke down because the Saudi government wouldn’t commit to certain safeguards against eventually using the technology for weapons.

Now the Trump administration has reopened those talks and might not insist on the same precautions. At a Senate hearing on Nov. 28, Christopher Ford, the National Security Council’s senior director for weapons of mass destruction and counterproliferation, disclosed that the U.S. is discussing the issue with the Saudi government. He called the safeguards a “desired outcome” but didn’t commit to them.

Abandoning the safeguards would set up a showdown with powerful skeptics in Congress. “It could be a hell of a fight,” one senior Democratic congressional aide said.

The idea of sharing nuclear technology with Saudi Arabia took an unlikely path to the highest levels of government. An eccentric inventor and a murky group of retired military brass — most of them with plenty of medals but no experience in commercial nuclear energy — have peddled various incarnations of the plan for years.

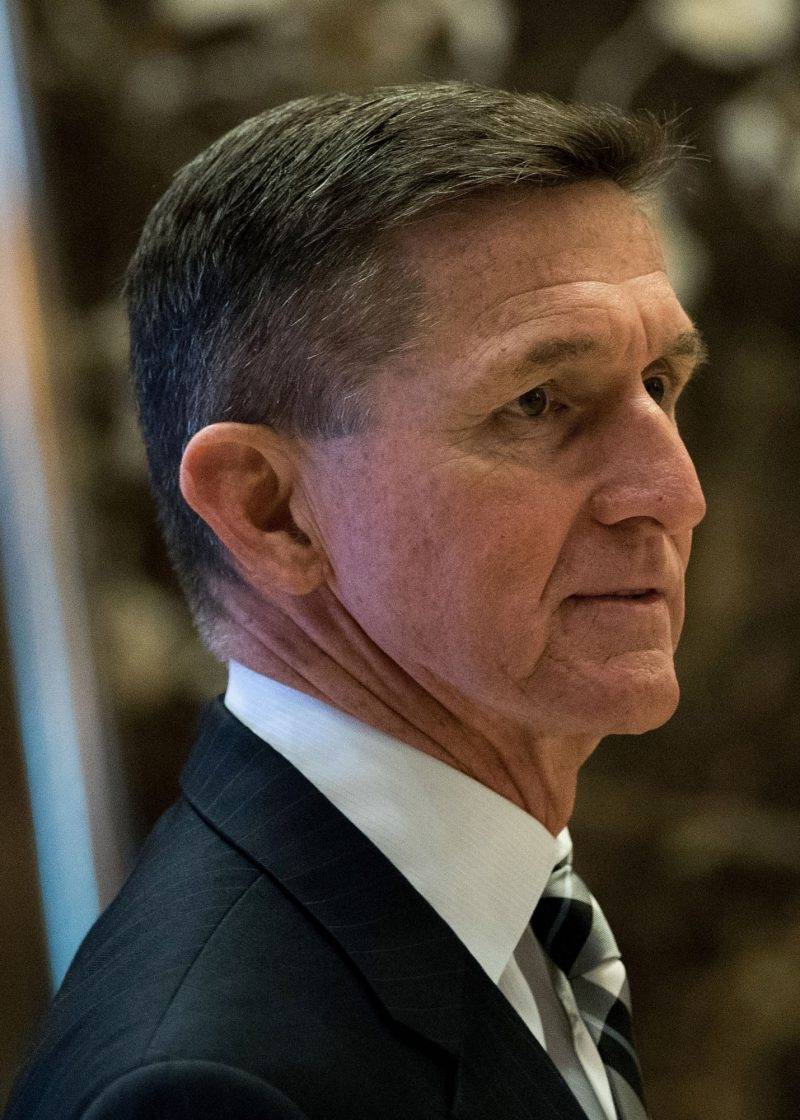

Many U.S. officials didn’t think the idea was serious, reputable or in the national interest. “It smelled so bad I said I never wanted to be anywhere close to that,” one former White House official said. But the proponents persisted, and finally found an opening in the chaotic early days of the Trump administration, when advisers Michael Flynn and Tom Barrack championed the idea.

The Saudis have a legitimate reason to want nuclear power: Their domestic energy demand is growing rapidly, and burning crude oil is an expensive and inefficient way to generate electricity.

There’s also an obvious political motive. Many experts believe the Saudis aren’t currently trying to develop a nuclear bomb but want to lay the groundwork to do so in case Iran develops one. “There’s no question: Why do you have a nuclear reactor in the Persian Gulf? Because you want to have some kind of nuclear contingency capability,” said Anthony Cordesman, a Middle East expert at the Center for Strategic and International Studies.

A Saudi spokesperson provided a written statement noting that the country’s electricity needs have grown “due to our population and industrial growth.” The statement noted that “The Kingdom of Saudi Arabia is a signatory of the Non-Proliferation Treaty, hence is diversifying its energy mix to serve its domestic needs in accordance with international laws and standards. The Kingdom has been actively exploring diverse energy sources for nearly the last decade to meet growing domestic demand.”

In recent months, the proposal has stirred back to life as the Saudi government kicked off a formal process to solicit bids for their first reactors.

The technology for nuclear weapons is different from that for nuclear energy, but there is some overlap. The fuel for a power plant can be used for a bomb if it’s enriched to a much higher level. Also, the waste from a power plant can be reprocessed into weapons grade material. That’s why nonproliferation experts generally prefer that countries that use nuclear power buy fuel on the international market instead of doing their own enrichment and reprocessing.

In 2008, the Saudi government made a nonbinding commitment not to pursue enrichment and reprocessing. They then entered negotiations with the U.S. for a pact on peaceful nuclear cooperation, known as a 123 agreement, after a section of the Atomic Energy Act of 1954. A 123 agreement is a prerequisite for receiving American technology.

The talks stalled a few years later because the Saudi government backed away from its pledge not to pursue enrichment and reprocessing, according to current and former officials. “They wouldn’t commit, and it was a sticking point,” said Max Bergmann, a former special assistant to the undersecretary of state for arms control and international security at the time those negotiations occurred.

U.S. officials feared a domino effect. Accords with the United Arab Emirates and Egypt restrict those countries from receiving the most sensitive technologies unless the U.S. allows them in another Middle Eastern country. “If we accepted that from the Saudis, nobody else will give us legally binding commitment,” a former State Department official said.

During that same period, the Obama administration was pursuing an agreement to stop Iran’s progress toward building a nuclear bomb while letting the country keep some domestic enrichment capabilities it had already achieved. The Saudi government publicly supported the Iran deal but privately made clear they wanted to match Iran’s technology. A former official summarized the Saudi position as, “We’re going to develop this kind of technology if they have this kind of technology.”

The Obama administration held firm with the Saudis because it’s one thing to cap nuclear technology where it already exists, but it’s longstanding U.S. policy not to spread the technology to new countries. As Saudi Arabia and Iran — ideological and religious opponents — increasingly squared off in a battle for political sway in the Middle East, Republicans argued that the Obama

administration had it backwards: It was enshrining hostile Iran’s ability to enrich uranium while denying the same to America’s ally Saudi Arabia.

One such critic of Obama’s Iran policy was Michael Flynn, a lieutenant general who was forced out as head of the Defense Intelligence Agency in 2014. Flynn quickly took up a variety of consulting assignments and joined some corporate boards. One of the former was an advisory position for a company called ACU Strategic Partners, which, according to a later financial disclosure, paid Flynn more than $5,000.

Flynn was one of many retired military officers whom ACU recruited. ACU’s chief was a man named Alex Copson, who is most often described in press accounts as a “colorful British-American dealmaker.” Copson reportedly made a fortune inventing a piece of diving equipment, may or may not have been a bass player in the band Iron Butterfly, and has been touting wildly ambitious nuclear-power plans since the 1980s. (He didn’t answer repeated requests for comment.)

By 2015, Copson was telling people he had a group of U.S., European, Arab and Russian companies that would build as many as 40 nuclear reactors in Egypt, Jordan and Saudi Arabia. Copson’s company pitched the Obama administration, but officials figured he didn’t really have the backers he claimed. “They would say ‘We have Rolls-Royce on board,’ and then someone would ask Rolls-Royce and they would say, ‘No, we took a meeting and nothing happened,’” recalled a then-White House official.

In his role with ACU, Flynn flew to Egypt to convince officials there to hold off on a Russian offer (this one unrelated to ACU) to build nuclear power plants. Flynn tried to persuade the Egyptian government to consider Copson’s proposal instead, according to documents released by Rep. Elijah Cummings, the ranking Democrat on the House Oversight and Government Reform Committee. Flynn also tried to persuade the Israeli government to support the plan and spoke at a conference in Saudi Arabia. (The trip would later present legal problems for Flynn because he didn’t report contacts with foreign officials on his application to renew his security clearance, according to Cummings. Cummings referred the information to Robert Mueller, the special counsel investigating Trump’s associates and Russia’s interference in the 2016 election. Flynn’s lawyer declined to comment.)

Copson’s outfit eventually splintered. A retired admiral named Michael Hewitt, who was to head up the security services part of the project, struck out on his own in mid-2016. Flynn went with him.

Hewitt’s new company is called IP3 International, which is short for “International Peace Power & Prosperity.” IP3 signed up other prominent national security alumni including Gens. Keith Alexander, Jack Keane and James Cartwright, former Middle East envoy Dennis Ross, Bush Homeland Security adviser Fran Townsend, and Reagan National Security adviser Robert “Bud” McFarlane.

IP3’s idea was a variation on ACU’s. Hewitt swapped out one notional foreign partner for another (Russia was out, China was in), then later shifted to an all-American approach. That idea resonated with the U.S. nuclear-construction industry, which never recovered from the Three Mile Island disaster in the 1970s and was looking to new markets overseas.

But nuclear exports are tightly controlled because the technology is potentially so dangerous. A 123 agreement is only the first step for a foreign country that wants to employ U.S. nuclear-power technology. In addition, the Energy Department has to approve the transfer of technology related to nuclear reactors and fuel. The Nuclear Regulatory Commission licenses reactor equipment, and the Commerce Department reviews exports for equipment throughout the rest of the power plant.

IP3 — whose sole project to date is the Saudi nuclear plan — never went through those normal channels. Instead, the company went straight to the top.

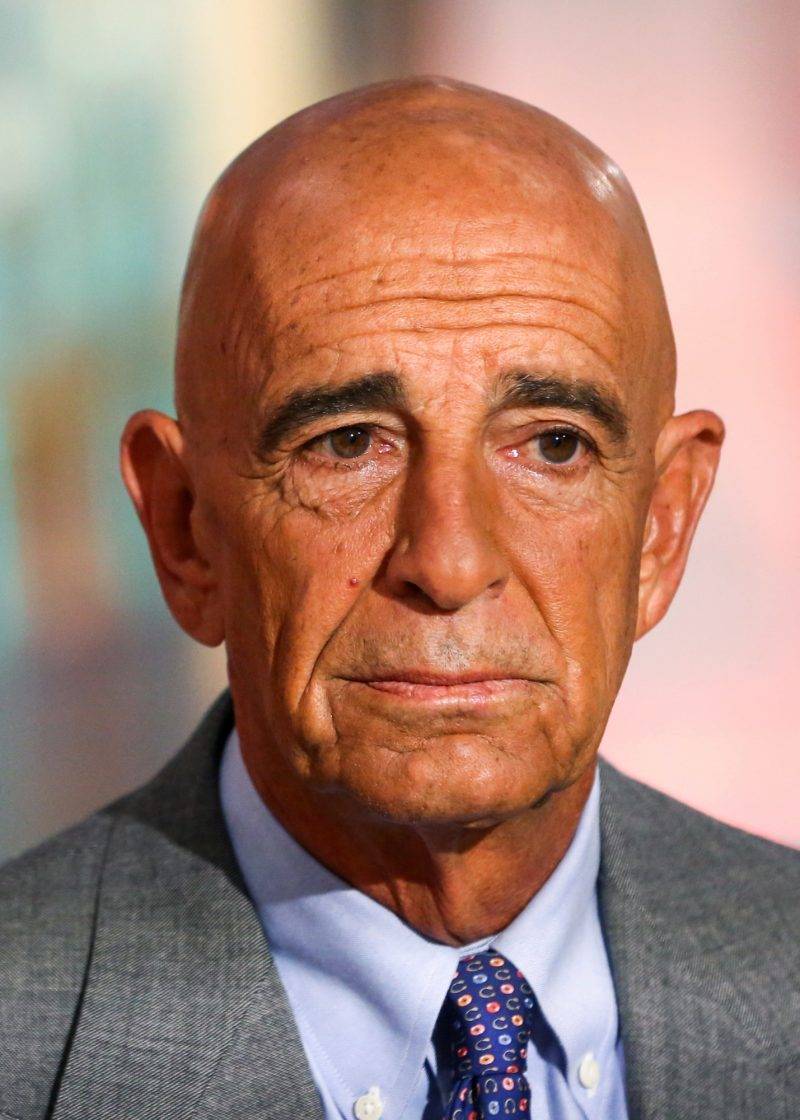

At the start of the Trump administration, IP3 found an ally in Tom Barrack, the new president’s close friend and informal adviser and an ultra-wealthy investor in his own right. During the campaign, Barrack wrote a series of white papers proposing a new approach to the Middle East in which economic cooperation would theoretically reduce the conditions for breeding terrorism and lead to improved relations.

Barrack wasn’t familiar with nuclear power as an option for the Middle East until he heard from Bud McFarlane. McFarlane, 80, is most remembered for his role in the defining scandal of the Reagan years: secretly selling arms to Iran and using the money to support Nicaraguan rebels. He pleaded guilty to withholding information from Congress but was pardoned by George H.W. Bush.

Nevertheless, Barrack was dazzled by McFarlane and his IP3 colleagues. “I was like a kid in a candy shop — these guys were all generals and admirals,” Barrack said in an interview. “They found an advocate in me in saying I was keen on trying to establish a realignment of U.S. business interests with the Gulf’s business interests.”

McFarlane followed up the meeting by emailing Flynn in late January, according to six people who read the message or were told about it. McFarlane attached two documents. One outlined IP3’s plan, describing it as consistent with Trump’s philosophy. The second was a draft memo for the president to sign that would officially endorse the plan and instruct his cabinet secretaries to implement it. Barrack would take charge of the project as the interagency coordinator. Barrack had discussions about becoming ambassador to Egypt or a special envoy to the Middle East but never committed to such a role. (McFarlane disputed that account but repeatedly declined to specify any inaccuracies. IP3 declined to comment on the memos.)

Flynn, now on the receiving end of IP3’s lobbying, told his staff to put together a formal proposal to present to Trump for his signature, according to current and former officials.

The seeming end run sparked alarm. National Security Council staff brought the proposal to the attention of the agency’s lawyers, five people said, because they were concerned about the plan and how it was being advanced. Ordinarily, before presenting such a sensitive proposal to the president, NSC staff would consult with experts throughout government about practical and legal concerns. Bypassing those procedures raised the risks that private interests might use the White House to their own advantage, former officials said. “Circumventing that process has the ability not only to invite decisions that aren’t fully vetted but that are potentially unwise and have the potential to put our interests and our people at risk,” said Ned Price, a former CIA analyst and NSC spokesman.

Even after those concerns were raised, Derek Harvey, then the NSC’s senior director for the Middle East, continued discussing the IP3 proposal with Barrack and his representative, Rick Gates, according to two people. Gates, a longtime associate of former Trump campaign chief Paul Manafort, worked for Barrack on Trump’s inaugural committee and then for Barrack’s investment company, Colony NorthStar.

By then, Barrack was no longer considering a government position. Instead, he and Gates were seeking investment ideas based on the administration’s Middle East policy. Barrack pondered the notion, for example, of buying a piece of Westinghouse, the bankrupt U.S. manufacturer of nuclear reactors. (Harvey, now on the staff of the House intelligence committee, declined to comment through a spokesman. In October, Mueller charged Manafort and Gates with 12 counts including conspiracy against the U.S., unregistered foreign lobbying, and money laundering. They both pleaded not guilty. Gates’ spokesman didn’t answer requests for comment.)

Ultimately, it wasn’t the NSC staff’s concerns that stalled IP3’s momentum. Rather, Jared Kushner, the president’s son-in-law and senior aide tasked with reviving a Middle East peace process, wanted to table the nuclear question in favor of simpler alliance-building measures with the Saudis, centered on Trump’s visit in May, according to a person familiar with the discussions. (A spokesperson for Kushner, asked for comment, had not provided one at the time this article was published; we’ll update the article if he provides one later.)

In recent months, the proposal has stirred back to life as the Saudi government kicked off a formal process to solicit bids for their first reactors. In October, the Saudis sent a request for information to the U.S., France, South Korea, Russia and China — the strongest signal yet that they’re serious about nuclear power.

The Saudi solicitation also gave IP3 the problem its solution was searching for. The company pivoted again, narrowing its pitch to organizing a consortium of U.S. companies to compete for the Saudi tender. IP3 won’t say which companies it has signed up. IP3 also won’t discuss the fees it hopes to receive if it were part of a Saudi nuclear plan, but it’s vying to supply cyber and physical site security for the plants. “IP3 has communicated its strategy to multiple government entities and policy makers in both the Obama and Trump administrations,” the company said in a statement. “We view these meetings and any documents relating to them as private, and we won’t discuss them.”

The Saudi steps lit a fire under administration officials. Leading the charge is Rick Perry, the energy secretary who famously proposed eliminating the department and then admitted he didn’t understand its function. (It includes dealing with nuclear power and weapons.) Perry had also heard IP3’s pitch, a person familiar with the situation said. In September, Perry met with Saudi delegates to an international atomic energy conference and discussed energy cooperation, according to a photo posted on his Facebook page. Perry’s spokeswoman didn’t answer requests for comment.

Other steps followed. Soon after, a senior State Department official flew to Riyadh to restart formal 123 negotiations, according to an industry source. (A State Department spokeswoman declined to comment.) In November, Energy and State Department officials joined a commercial delegation to Abu Dhabi led by the Nuclear Energy Institute, the industry’s main lobby in Washington. Assistant Secretary for Nuclear Energy Edward McGinnis said the administration wants to revitalize the U.S. nuclear energy industry, including by pursuing exports to Saudi Arabia. The Department of Commerce’s International Trade Administration and the Energy Department are organizing another industry visit in December to meet with Saudi officials, according to a notice obtained by ProPublica. And in the days before Thanksgiving, senior U.S. officials from several agencies met at the White House to discuss the policy, according to current and former officials.

The Trump administration hasn’t stated a position on whether it will let the Saudis have enrichment and reprocessing technology. An NSC spokesman declined to comment. But administration officials have begun sounding out advisers on how Congress might react to a deal that gives the Saudis enrichment and reprocessing, a person familiar with the discussions said.

Senators have started demanding answers. At the Nov. 28 hearing before the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, Ford, the NSC nonproliferation official who has been nominated to lead the State Department’s Bureau of International Security and Nonproliferation, testified that preliminary talks with the Saudis are underway but declined to discuss the details in public. As noted, Ford wouldn’t commit to barring the Saudi government from obtaining enrichment and reprocessing technology. “It remains U.S. policy, as it has been for some time, to seek the strongest possible nonproliferation protections in every instance,” he told the senators. “It is not a legal requirement. It is a desired outcome.” Ford added that the Iran deal makes it harder to insist on limiting other countries’ capabilities.

Sen. Ed Markey, the Massachusetts Democrat who led the questioning of Ford on this topic, seemed highly resistant to the idea of the U.S. helping Saudi Arabia get nuclear technology. “If we continue down this pathway,” he said, “then there’s a recipe for disaster which we are absolutely creating ourselves.” Markey also accused the administration of neglecting its statutory obligation to brief the committee on the negotiations. (The White House declined to comment.)

Any agreement, in this case with Saudi Arabia, would not require Senate approval. However, should an agreement be reached, Congress could kill the deal. The two houses would have 90 days to pass a joint resolution disapproving it. The committee’s ranking Democrat, Ben Cardin, suggested they wouldn’t accept a deal that lacked the same protections as the ones in the UAE’s agreement. “If we don’t draw a line in the Middle East, it’s going to be all-out proliferation,” he said. “We need to maintain the UAE’s standards in our 123 agreements. There’s just too many other countries that could start proliferating issues that could be against our national interest.”

Bob Corker, the committee’s chairman, has been a stickler on nonproliferation in the past; he criticized the Obama administration for not being tough enough. Corker isn’t running for reelection and has criticized Trump for being immature and reckless in foreign affairs, so he’s unlikely to shy away from a fight. (A spokesman declined to comment.) “The absence of a consistent policy weakens our nuclear nonproliferation efforts, and sends a mixed message to those nations we seek to prevent from gaining or enhancing such capability,” Corker said at a hearing in 2014. “Which standards can we expect the administration to reach for negotiating new agreements with Jordan or Saudi Arabia?”

Via ProPublica