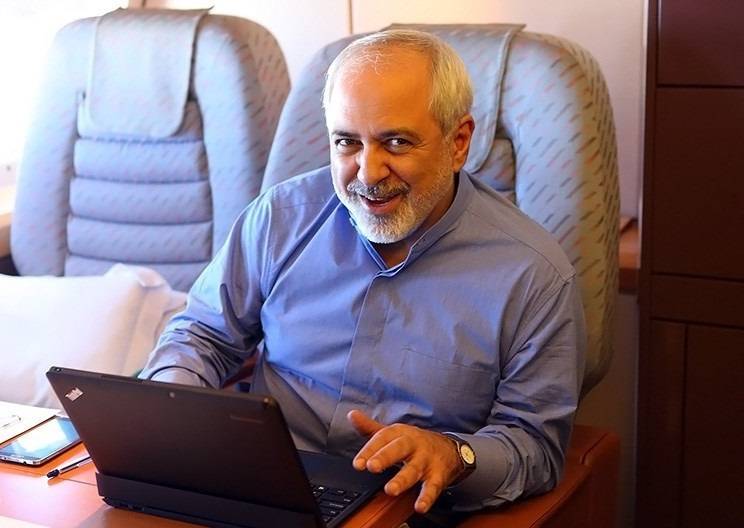

At the Munich Security Conference in February, Iranian Foreign Minister Javad Zarif repeated his administration’s proposal to engage Iran’s Persian Gulf neighbors with the goal of creating a Persian Gulf Security Agreement. According to Zarif, the talks for such an agreement would be “founded on dialogue, common principles, and confidence building measures” with the goal of avoiding “turmoil or potentially far worse.” Deputy Foreign Minister Abbas Araghchi referenced his boss’s plan during a visit to the British think tank Chatham House the following week, repeating the goal of a Helsinki-inspired non-aggression pact that would first begin with confidence-building measures in tourism, pollution, and drug trafficking. Of course, this proposal is largely aimed at Saudi Arabia.

This type of plan, if ideally pursued by all parties, would echo the hope President Obama had during his administration. In what later turned into a controversy in Riyadh, Obama said:

The competition between the Saudis and the Iranians—which has helped to feed proxy wars and chaos in Syria and Iraq and Yemen—requires us to say to our friends as well as to the Iranians that they need to find an effective way to share the neighborhood and institute some sort of cold peace… An approach that said to our friends “You are right, Iran is the source of all problems, and we will support you in dealing with Iran” would essentially mean that as these sectarian conflicts continue to rage and our Gulf partners, our traditional friends, do not have the ability to put out the flames on their own or decisively win on their own, and would mean that we have to start coming in and using our military power to settle scores. And that would be in the interest neither of the United States nor of the Middle East.

The key here is the reference to a cold peace between Saudi Arabia and Iran serving U.S. interests. After taking the reins of Persian Gulf security in 1979, the United States has been bogged down in costly interventions in the region ever since. In Iraq alone, the United States has spent $821 billion to date, which led to the creation of the Islamic State (ISIS or IS) in a terrible strategic error. Of course, the United States has faced blowback in the region on many occasions. Whack-a-Mole clearly has not been a valid foreign policy strategy.

To prevent another foreign policy catastrophe, Obama signed a nuclear deal—the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA)—with Iran and the other members of the P5+1 in July 2015. This was after barely avoiding an Israeli strike on Iran’s nuclear sites that the United States would surely have felt forced to support. With the JCPOA, the United States opened avenues of communication that proved critical on multiple occasions and eliminated the immediate chance of war.

Now, as tensions between Saudi Arabia and Iran continue to boil in various arenas, the Persian Gulf region again requires heavy diplomacy. It would also not be unprecedented for Tehran and Riyadh to engage in such diplomacy. Back in 2001, Iran and Saudi Arabia reached an agreement that dealt with terrorism, economic crimes, and drug smuggling. This agreement has some overlap with the confidence-building measures currently proposed and could be the inspiration for attempting a new understanding.

Of course, the current regional environment is infinitely more complicated and relations are arguably at an all-time low, which is why it is even more critical for the United States to encourage such diplomacy if it wants to avoid finding itself in another conflict in the Middle East. Notably, the most recent National Defense Strategy emphasized the “re-emergence of long-term, strategic competition between nations” as being the primary interest of the United States, especially in the context of China and even Russia, but it included limited interest in the Middle East. Regardless of who’s holding the White House, the United States has declared that its long-term interests are not served by Middle Eastern quagmires. To serve its own interests, the United States should allow a “cold peace” to endure through diplomatic engagement, which will provide itself the flexibility to pivot to more pressing issues.

Saudi Resistance

Two main reasons prevent Saudi Arabia from reciprocating Iran’s call for regional engagement: the Mohammad Bin Salman (MbS) Doctrine and President Trump.

On the first point, Saudi Arabia’s influential and hawkish Crown Prince MbS last year said “we won’t wait for the battle to be in Saudi Arabia. Instead, we’ll work so that the battle is for them in Iran.” Between detaining Riyadh’s elite at home, isolating Qatar, and intervening in Yemen, which has led to over 22 million people requiring aid, MbS has implemented an aggressive strategy at home and abroad. Essentially, the MbS Doctrine is to confront your perceived enemies head-on.

The decisions have been questionable: animosity has risen among the royals, Qatar has only pivoted further from Saudi Arabia, and the Yemen intervention has failed to achieve its goals. The confrontational tone and policy decisions of MbS are not conducive to diplomacy. It remains to be seen whether advisors in his administration are willing or able to direct MbS towards a different strategy.

So far, this appears unlikely as Saudi Foreign Minister Adel al-Jubeir, in reply to Zarif’s proposal, said on the same day of the Munich Security Conference, “the problems in our region began with the Khomeini Revolution in 1979, Khomeini Revolution unleashed sectarianism in the region.” Whatever the grievances between the two countries, responding to engagement offers with references to the past is a simple way of saying no.

On the second point, Trump has yet to pressure the Saudis to change strategies. During his time on the campaign trail, Trump aggressively attacked the Iran Deal, repeatedly calling it a “disaster,” which was music to Saudi Arabia’s ears. In response to Saudi Arabia’s sudden embargo on Qatar, Trump tweeted “I have great confidence in King Salman and the Crown Prince of Saudi Arabia, they know exactly what they are doing.” In the most straight-forward signal, Trump approved a $110 billion arms sale to Saudi Arabia in a trip there last year. To be fair, a portion of the sales was worked out initially under the Obama administration, who also green-lighted the Yemen intervention for Saudi acceptance of the Iran Deal. Also, Saudi Arabia’s request to build nuclear reactors with indigenous enrichment have concerned proliferation experts, especially in the context of Trump’s passive approach to the kingdom. To put it simply, MbS has little reason to change strategy under the Trump administration. He knows he has the consistent backing of the United States for his zero-sum approach, which provides the necessary diplomatic and material cover to continue course. This is also why bills coming from Congress questioning the U.S. support for MbS’s Yemen intervention remain critical.

Advancing US Interests

Speaking to the Iranian side, President Rouhani has been adamant that the United States not play a direct role in the Persian Gulf Security Agreement. External security guarantors are antithetical to the Islamic Republic. This may complicate matters as the United States guarantees Saudi Arabia’s security and U.S. Central Command remains present in the Persian Gulf. However, Iran is well aware of the close military cooperation of the two countries and would tacitly accept consultations between Riyadh and Washington during the negotiations. Most importantly, negotiations succeeded in 2001 under the same prerequisite. Also, Saudi Arabia and the United States accuse Iran of supplying missiles to the Houthis in Yemen, which have ended up landing in Riyadh. Saudi Arabia called this an “act of war,” which obviously leaves diplomacy on the back burner. However, Iran counters that Saudi Arabia has directly or indirectly supported Sunni extremists, even going as far as accusing Saudi Arabia of being behind the IS attack in Tehran last year. These are the exact type of back-and-forth accusations that require diplomatic communication to solve.

To be clear, the status quo is detrimental to the United States interests in the region. If Saudi Arabia continues to receive blanket support from Washington, Iran could feel the balance of power shifting and see the need to increase its relatively moderate engagement in Yemen or in other arenas. This will prove to be a dangerous game that could again distract the United States. An agreement, on the other hand, could increase communication between Riyadh and Tehran, decreasing risks regionally. Zarif has repeated that this agreement should only involve issues in the Persian Gulf. Over time, however, this engagement could help end Saudi Arabia’s intervention in Yemen and even more ambitiously help find a political solution in Syria that would benefit all the parties involved.

The JCPOA provided the United States with an easy platform to back diplomacy between the two powers. Although that opportunity is now in the past, Trump’s cabinet members should ultimately see the realism behind encouraging Saudi Arabia to test Iran’s offer and make the case to Trump himself. After all, the National Defense Strategy calling for a shift in national priorities away from the Middle East was written under the supervision of Trump’s own secretary of defense. The chance that negotiations between Iran and Saudi Arabia may not go anywhere should not prevent trying altogether. The success of such an agreement will not only serve the long-term strategy of the United States, but it could also serve those suffering in the various conflicts across the Middle East.