Elizabeth grew up in the Scottish Highlands. Her father was the manager of the Bank of Scotland. Along with two other of her siblings she decided to pursue a career in medicine. She began her medical training at the prestigious Glasgow Medical School in 1901 when she was 18. This was also the time when women were just being allowed to apply and be considered a place at the School. There was only one other female who had graduated in the medical field from Queen Margaret College before Elizabeth. Miss Ross excelled in Midwifery and also obtained her certificate in Chemistry and Ophthalmology and later in her career she completed a diploma in Tropical Medicine.

It was apparent to anyone who met Elizabeth that she was not a conventional person. She was petite in stature but adventurous in spirit. As soon as she noticed an advertisement in the papers seeking a medical assistant in Persia, she applied and travelled to Persia where she became the medical assistant to an American physician and worked in Shiraz and Isfahan. She later wrote that fate came to her in the form of advertisement while she was dreaming of other lands – embedded in her imagination from earlier years were, The Life and Strange Surprising Adventures of Robinson Cruseo and the stories of One Thousand and One Nights.

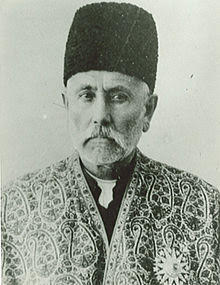

Later she left the American doctor and began practicing on her own. It was during this early period that she was approached by a Bakhtiari chieftain to become the doctor of his Haft Lang tribe. The chieftain was no other but Najaf-Qoli Khan Bakhtiari also known as Samsam al-Saltane (1846-1930). It was a year later that she accepted the offer. Having grown up in the Highland of Scotland she wrote, “There was something about the rugged mountaineer which won my heart, conjuring up as it did reminisces of Ross-shire and its Highland chieftains. From that day, dates my sympathy towards the Bakhtiaris.” It was in the winter of 1909 that she joined the Haft Lang tribe as their medical advisor. It was in the same year that Sardar Asaad Bakhtiari (1856–1917) the brother of Samsam al Saltane, with his forces captured Tehran as part of the revolutionary campaign to force the central government to establish democratic reform.

In her observations Miss Ross makes comparison between those Bakhtiari custom and tradition that she finds analogous in her Scottish culture, for example, on education she writes, “Like the Scotch the Bakhtiari are the believers in the system of co-education, and at the age of seven or eight years boys and girls alike have to go for four or five hours daily to the Muallam or private tutor of the household. They study both Arabic and Persian and their studies continue for a variable length of time. It is not at all uncommon to see a married woman with one or two children still pursuing her educational studies.”

On Bakhatiaris’ practical nature Elizabeth makes insightful and witty statement. She writes, “They complain bitterly of the paucity of literature, for, as I remarked before, the Bakhtiari character is absolutely devoid of any strain of poetry or romance….Their one desire is to read history. There is a Persian book published which I have not seen, but of which I have frequently heard. It is the favourite literature of many of the Bibis. It evidently recalls the chief events of the French revolution…beheading of the Charles I…Restoration of Charles II… I was most anxious to see this book, but there is apparently a scarcity of copies and, whenever I asked for it, it had always been ‘just lent it to a neighbouring Bibi.’

Elizabeth found the knowledge and the curiosity of the Bibis about history astonishing. She recalls an episode that took her by surprise, “I remember once being rather taken aback by an historic question. I had performed rather a serious operation on a patient and sitting beside her a few hours afterwards, I was startled by the inquiry: “What happened to the General Monk after he brought back Charles II? I have so often wondered.”

Dr Ross also reveals how resourceful the Bibis were in the medical field: “The Bakhtiari Bibis are great doctors and prescribe not only for themselves, but for their villages and dependents. Most of them possess French medicine chests which they have obtained from Tehran, and they show a surprising acquaintance with European drugs and their properties.”

Elizabeth left for London in 1913. The purpose for leaving Persia was a well-deserved rest from her full-time service to the Bakhtiaris and she also wanted to complete her diploma in tropical medicine. She went from Madras to London on the SS Nigaristan. On her return she was on SS Glenlogan travelling from Scotland to Kobe, Yokohama and Hong Kong. Her fluent Persian surprised everyone on board and the Persians at Penang and Singapore invited her to their homes. On board the ship she acted as the vessel’s doctor on both voyages. ‘She is now widely believed to be the world’s first female ship surgeon.’

Not long after her return it was the outset of First World War and casualties were already mounting. The Russian government asked her to join the First Military Reserve Hospital in Serbia which she accepted, realising she was desperately needed there. In 1915 only weeks into her service, Elizabeth, whose Persian given name was Gulafruz, (Blazing Flower) tragically whittled away under the intense heat of the typhus fever on her 37th birthday, in Kragujevac Serbia.

Miss Ross left behind a memoir, A Lady Doctor in Bakhtiari Land which was posthumously published by her brother in 1921. Her book is considered to have been influential in shaping the modern travel writing canon. It is also peppered with great humour and it is hard in some parts not to laugh out loud. In the book she also challenges some statements written by other writers regarding the Bakhatiaris most notable by Lord Curzon. The other female English writers who had written about the Bakhtiraris were Isabella Bird and Vita Sacksville West, neither of whom was as insightful as Miss Ross simply because they were passing through and spent little time with the tribe where as Dr Ross lived among them for good number of years.

Although as yet no biography of her has been published, the very little and scattered information that can be found on her life and work reads like a Hollywood epic. Her relatively short life was full of daring adventures and selfless service to people who needed her medical expertise. The Haft Lang tribe made her an honorary chieftain. She had to be rescued twice when attacked and robbed by the bandits on her way from Isfahan to Shiraz. When the press in England found out about her predicament it criticised the Qajar government for the lawlessness in Persia where a woman doing humanitarian work is harassed, robbed and in danger of being killed. It is quite possible Bakhtiaries were the ones who rescued her from the bandits or her connection to them ensured her freedom. She lived and worked with the most politically active ethnic group, in the middle of the Constitutional Revolution. At the end of her book she briefly outlines four possible scenarios for the future of Persia which illustrates that she also had one eye on the global political situation and how it was going to shape the destiny of Persia.

An extraordinary claim by the Newcastle Journal only adds to Elizabeth intriguing life and her humanitarian vision for Persia. According to the journal she was offered the directorship of a new hospital for women in Tehran. This is proof that she had long term plans to improve the health condition of women and the general population and was planning to return to Persia and perhaps spend the rest of her life there. To further validate the Newcastle Journal report, Elizabeth’s departure to England in 1913 most probably was to prepare her better for the task ahead for she used the opportunity to complete her Diploma in Tropical Medicine (DTM). DTM was relatively a new discipline having been established as early as 1899. Although Persia is not part of the tropics but at the time they shared many similarities in the diseases prevalent in both regions. Control and eradication of malaria and tuberculosis were high on the list in the DTM training. In the Qajar period (1796-1925) malaria was wide spread. “The estimated total population of Iran in 1921 was 12 million, of which around 60 percent resided in highly endemic malaria areas, and annually between 4 and 5 million people had contracted the disease, which was responsible for 30 percent to 40 percent of all mortalities in Iran.” Poor sanitation and hygiene were also responsible for a host of other diseases and subsequent fatalities. Elizabeth knew her work was much more needed in Persia as a whole. The affluent and educated Bakhtiraris knew how to look after themselves and on occasions she may have even felt not needed but the country was in a disastrous health condition as the statistics indicate.

It is quite remarkable for a single woman and a foreigner to come so far in a patriarchal and Islamic country in the most difficult and volatile political climate. And, how much more she would have achieved had she survived the typhus epidemic. It is apparent from her commitment to her adopted country she had one thousand and one beautiful visions for Persia.