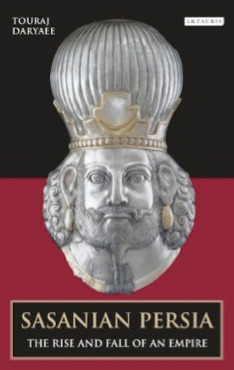

Introducing his book, Sasanian Persia, the Rise and Fall of an Empire, Dr. Touraj Daryee begins with a humble claim: there were no books in English dealing exclusively with Sasanian history, so he wrote one. Simple enough! But imagine the need if there were no English language books on Roman history. To gain insight into elements of their own governments, American and British students would have to study their own history through foreign eyes. For Iranian-Americans, particularly the younger generation with English as their first language, Sasanian Persia fills a correspondingly significant gap. Daryaee remains similarly down-to-earth throughout his reader-friendly yet erudite narrative. But by the final page of the book, there is a strong sense that the author has been generous far beyond his modest claim. Dr. Daryaee kindly agreed to answer some questions about Sasanian history that would be of interest to Iranian-American readers who also keep up with events in modern Iran.

Ari: One of the most striking revelations of your book is the inseparability of state and religion during the Sasanians. “Know that kingship is religion and religion is kingship…” according to Zoroastrian text. What are some of the ways that the philosophy of inseparability has played out in Iran’s history since the Sasanians, for example Safavids, Constitution era, IRI today?

Daryaee: This idea of the connection and the survival of one based on the protection of the other has repeatedly appeared in Iranian history. The Sasanians present the earliest and clearest example that is expounded in Zoroastrian Middle Persian [Pahlavi language] texts. The Abbasid caliphs used this concept when they translated the ideas into Arabic, using them as tools for legitimizing their rule.

We see these ideas circulating in Medieval Persian Mirror for Princes literature [how-to guides for rulers] as well, but not to the extent that you find in the Sasanian or the early Abbasid period. But then again, it is in the Safavid period that it makes a strong reappearance.

With Fath Ali-Shah Qajar [the time of Iran’s humiliating defeats by Russia] we begin to get a new Shi’i interpretation of the Islamic tradition that during the Ghaybah or occultation of the Hidden Imam, the most capable person should rule, and that is the Faqih . Mullah Ahmad Naraghi brought one of the earliest interpretations of this in the 19th century. Of course this idea then became the basis for Ayatollah Khomeini’s concept of an Islamic state, where religion and state must be connected. After 1800 years, we have come back full circle!

Ari: The natural mechanisms super-gluing state and religious power–Sasanian, Roman, or empires elsewhere–can be readily seen in your narrative. This makes us wonder if, ironically, secularism is not a historic miracle. On a historic timescale, how stable are modern secular governments such as Turkey or the United States?

Daryaee: In the pre-modern times the idea of secularism is a rarity, if it ever existed. God(s) existed and was everywhere. It was not like now where the synagogue, church or mosque is the only place where you feel in the presence of God in a sacred space, and the outside world is a “secular/profane” place. Every place was sacred space and God was present everywhere, even though there are rare instances that we hear of those who don’t believe in a God in Mesopotamia.

But Turkey has successfully been able to balance religion and the state in a way that has become stable. Of course early on in the century it was violently anti religious and destroyed the power of the clerical establishment. This of course was never the case in Iran, at least since the sixteenth century.

For the US, it is a bit more interesting. In recent decades we see that religious groups are pushing for power. Who knows, one day the U.S. may be more like Iran than we would imagine!

Ari. Pabag [[Babak] the father of the first Sasanian king Ardeshir I was a fire temple priest, and Ardeshir I– along with other early Sasanian kings–held both state and considerable religious power. But later some of this religious power flowed back into the non-royal priesthood. So here’s the reverse of the previous question: why does power tend to separate between religion and state?

Daryaee: Making the Sasanian family from a priestly lineage is a Zoroastrian tradition. At times, the kings saw the power of the Zoroastrian priests and tried to counter it. At other times they used them to combat other dangerous elements / religious traditions. For example, Zoroastrianism was used to put down Mani and his Manichaean tradition, which had become popular. In the sixth century the king used Mazdak, a Zoroastrian priest to break the power of the nobility and institute changes through idea of a social / religious revolution.

But the King of Kings ruled over a large group of Christians, Jews and others, and as time went on, the state needed to promote the King’s Law over all the religious communities and so it confronted the Zoroastrian clergy as much as it could.

Ari: The word “theocracy” does not appear in your book on Sasanian Persia during any of its periods. Did you consciously avoid the term?

Daryaee: I don’t think the Sasanian Empire was a theocratic state. A clergy was never head of the state, but it came close to it. Although many are tempted to compare it with the modern times in Iran, I wanted not to do this. So you may say it was a conscious decision.

Ari: The high priest Kerdir’s influential attempt to associate a particular geographic region, Iranshahr, with a particular religious sphere, Zoroastrianism, is reminiscent of how Judaism associates itself with the land of Israel. Yet you state the Iranian identity survived the fall of the Sasanians and Zoroastrianism as state religion precisely because there was enough religious tolerance to allow non-Zoroastrians to also feel Iranian. In the light of Israel’s modern resurrection, how would you evaluate Kerdir’s attempt to associate land with religion?

Daryaee: This is a very interesting and good question. The idea of Iran / Iranshahr came from the Zoroastrian tradition which the Sasanians propped up (using the Avestan tradition). But by the sixth century there was a cultural idea of Iranshahr which encompassed Christians and Jews as well, because they themselves called themselves either Iranian or from Iranshahr. So the jump had been made from a religious/ethnic to a cultural and imperial–I hesitate to use secular–idea of Iran / Iranshahr. Thus, Iran as an idea survived the fall of the state religion.

If Israel is to do this–and she probably can–some elements in the population would have to win out in the debate.

Ari: By modern reckoning Wahram V (Bahram e Goor) would be Jewish, since his mother was Jewish. Given that Sasanian Zoroastrianism went so far as to encourage consanguinity [marriage within the family], why was marrying outside the religion even tolerated? Did the wives convert to Zoroastrianism?

Daryaee: These marriages cemented the relations between the king and the community. Yes, in fact Wahram V could be considered a Jewish king in the eye of the Jewish population. Next-of-kin-marriages seem to have been encouraged more after the Muslim conquest (at least I think), in order to keep the wealth of the Zoroastrian families from disappearing. I assume there was much more marriage between Zoroastrians, Christians and Jews than we think.

Ari: Shapur I tolerated the prophet Mani to dilute Zoroastrian power. Kawad I [Ghobad I] courted Madak’s socialist religion not only to subvert the power of the Zoroastrian priesthood, but also to weaken the nobility. In practical terms, what did these kings want that religious power and nobility got in the way of? In other words, why try to weaken the crown’s spiritual and material support structure?

Daryaee: These kings were using religion or religious men to counter the religious hierarchy or entrenched nobility. They needed to make changes and this could be done with the help of such figures. These are the times you need the aid of the masses or a group of them who are willing to move and shake things.

Shapur was perhaps thinking of a universalist religion, just like Christianity in the 3rd CE, and Kawad was thinking of creating or reforming Zoroastrian laws and breaking the back of the nobility and the clergy.

Ari: From your book it seems that the Khusro I’s [Anooshirvan] social reforms and subsequent reputation for justice should be partly credited to his father Kawad I who began the reforms under the influence of Mazdak ideology. Despite Mazdak’s ill fate and bad name, could he have been the ideological hero that saved the empire from collapse?

Daryaee: Mazdak’s appearance certainly brought about much reform. Mazdak was not the cause but the symptom of a declining Iranshahr in the fifth century CE. Mazdak has gotten a bad name because his enemies have written history and nothing survives of his own accounts. But he inspires later movements in the early Islamic period. So he must have resonated with the masses.

Ari: Your book suggests that the empowerment of the dehghan class [local landlords] and the resulting localized loyalties may have been one reason the empire fell to the Arabs. The Iranian nation seems to have been punished by this sharing of power that has a component in the direction of democracy. Could this historic memory still be informing our hesitant attitude towards the sort of distributed power characteristic of democracy?

Daryaee: In one way, Khusro tried to spread the wealth and power a bit at the cost of the great houses. I don’t think that was a real problem, although some of these people thought of their own interest first and foremost during the Arab Conquest. But this is a trend in pre-modern history throughout the world, as the “nation” is our modern view of the concept of that late antique period in Iran. Sure, there was Iranshahr, and the monarchy tried to espouse it–successfully to some extent–but many in the localities may not have thought of the “nation” concept as important.

Ari: You cite reasons as to why Sasanian Zoroastrianism had a dim view of artisans and merchants, such important tasks being primarily the occupation of minorities and émigrés who were sometimes forcibly brought in. Could this ambivalence towards industry–continued into the modern era–have been a cultural contributor to Iran resisting industrialization?

Daryaee: This is also a very interesting question and idea, which may be true. Although in the Islamic period, the religion was very open and favored business, and so there may be different ways to think about this.

Ari: Scientific treatise, geography, botany, zoology, history, were appended to religious texts, instead of being allocated separate books. Is this why so much was lost after the Islamic invasion? Worldly Knowledge was stored with the burnable stuff?

Daryaee: I tend to think of the issue differently. In the Sasanian period interest in Greek (Hellenic) and Indian science is very much in play. Schools are set up, a hospital (Jundishapur) was built, and translators translated everything into Middle Persian / Pahlavi for the king and the court. We have glimpses of this in references, as well as evidence in Middle Persian literature. For example, Middle Persian texts tell us that kings ordered books on geography (zamig-paymayig). We have direct quotations from Aristotelian texts in Middle Persian, etc.

What happened in the Abbasid period was to mimic the Sasanians and so a translation movement came about where all these texts were translated into Arabic (the new language of the new empire). Since these Middle Persian texts were of no use in the early Islamic period, they withered, but the religious material survived with the Zoroastrian priests who needed to have them.

Ari: The Sasanians tried to connect themselves to the Avestan Kianid kings, bypassing and erasing real history even from the likes of Ferdowsi. Today we rename streets and monuments to hide our past and shape it to our advantage. From a strictly non-judgmental point of view, are such measures necessary for the stability of regimes?

Daryaee: What you have in the Shahnameh is really the Sasanian vision of the origin and the history of Iranshahr. The Sasanians created a sacred history of Iran, which should necessarily begin as described in their religious text, i.e., the Avesta. In the Yashts of the Avesta, the Kayanids loom larger than life. The Sasanians used them and modeled themselves after them. In such a scheme there was no need for the Achaemenids whose memory was reduced to Dara son of Dara (Darius III), because he had been defeated by Alexander of Macedon.

Every dynasty and regime tries to rewrite history and push issues that makes them legitimate. But if the Khoday-namag (book of kings) of the Sasanian period had been lost, and not given its Persian form, the Shahnameh, we would have lost our identity and would have become just another Muslim country. Of course this did not happen.

Ari: From the descriptions in your book, a reader can suspect that the Iranian Shiite tradition of azaadari, perhaps even the self-mutilation rituals of Ashura have roots in some regional Sasanian Zoroastrian rituals. The recommended age of marriage for a girl was nine, and women had to cover themselves and not wear makeup. In what other ways would today’s Shi’ism look familiar to a devout Sasanian Zoroastrian?

Daryaee: As a historian, I am somewhat weary of making direct connections, but still you see continuity. Of course we have to remember that Iran was dominantly Sunni for almost a 1000 years before Shi’ism became the state religion during the Safavid period.

But we see local customs in the Sasanian period that show passion plays–Sug I Siyavash is a good example. The idea of marriage when you are young was the norm in antiquity as people did not live long like today, and having offspring early was most important. I would even contend, as some evidence has come to light, that the idea of contractual or temporary marriage is found in the Sasanian period and then in Shi’sim. What makes such a connection so interesting is that even in the Arab Shi’i countries the idea of Mut’a or temporary marriage is not really accepted and it is only in Iran that you have this idea taking hold. How is it that we had this practice in Iran among the Sasanian Zoroastrians of 1, 3, 10-year contracts? Also, the Jews mention in their Talmud that the Iranians had this practice in the Sasanian period. Then in Iran of the Islamic period we again face a similar issue.

I should note there are many more laws in common between Shi’ism and Zoroastrianism of the Sasanian period. These need to be studied and worked out of course.

Ari: Thank you Dr. Daryaee. Your book was a fascinating read. Everything felt so familiar in Sasanian. Iran–including the short passages in Middle Persian. For a modern Iranian layperson it certainly stirred up a lot of soul searching, as you may have noticed from the questions.

Daryaee: I too think the Sasanians are very much with us, or we are the product of a plan they set up 1800 years ago! That is why I am interested in them.