Willem Marius Floor was born in Utrecht, the Netherlands. After finishing high school, he attended the University of Utrecht were he studied Arabic and eventually became interested in Persian. Ever since, he has been engaged in the study of Iran: From the Safavids to the Qajars, from Bushehr to Bandar Abbas, from writing about bread in Iran, to the history of sexual relations, theatre and public health in Iran; you name it.

Willem Floor was recently invited to visit Iran. He gave numerous talks at different academic institutions, among them, Farhangestan-e olum-e pezeshki

Daneshgah-e Tehran, goruh-e tarikh-e Daneshgah-e Tehran, Bonyad-e Iranshenasi, Sazman-e asnad-e melli, and Khaneh-ye Ketab.

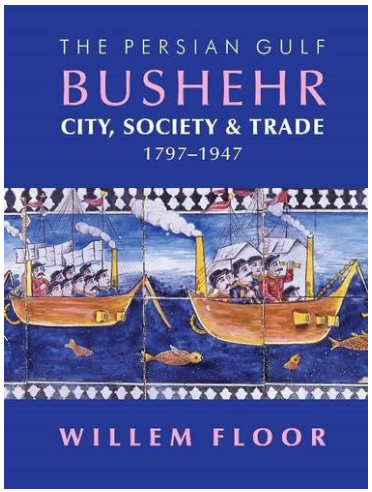

His recent 700-page book on the history of the city of Bushehr was published in 2017 by Mage Publishers.

He continues to write and enjoys what he writes. Speaking about Iran and Iranians, he comments, “Iranians are probably the most courteous and hospitable people I know.”

You worked for the World Bank and were in Africa. How and why did you become interested in Iran?

At the University of Utrecht, I studied among other things Arabic and one of my colleagues, a student, who also took Persian, suggested that I would enjoy that as well. So I did, and fortunately, the first book that we had to read was Tarikh-e Beyhaqi, which, in my view, is one of the best histories written. As I enjoyed the story so much, I became interested in Persian history and got hooked and still am. I said, fortunately, because the second book we had to read was Attar’s Mantiq al-Tayr, which I did not like at all and bored me.

You have written a number of books on Iran, almost one a month! (of course an exaggeration on my part). Are these books more reference books or analytical?

Whether my books are reference books or analytical depends on the user. When the user mines them for information they are reference books; when the user wants to get my view on the subject that I wrote about, I suggest that they are analytical. After all the term suggests, inter alia, that an author brings order to a large set of data with a view to make the result comprehensible to the reader.

How many books are we talking about ?

I think I have written more than 40 books, which includes a number of translations and one text edition. I don’t write yet one book per month, I am just training for that moment and it needs a lot of practice, which is the reason why I have not achieved such a lofty output, but I have not given up hope yet.

What is your favorite book of the ones you have done so far?

I have no idea what my best book is and have never given this a thought. In fact, I like all my books for the simple reason that I usually write about a subject that I don’t know much or anything about. My books are first and foremost written for myself, because they are the result of my attempt to find out what I can learn about a subject that may just be a term to me. I have written books that initially I intended to be an article, because when I begin my research and start writing I have no pre-set ideas where I want to end up. In short, having researched a subject and learnt more than I knew about it is the best thing.

Recently you went to Iran and have become the honorary citizen of Bushehr. How come?

Well, I have not become an honorary citizen of Bushehr, although I have been told by almost everybody there that they consider me to be a ham-shahri and a real Bushehri. The reason for this enthusiasm perhaps is due to the fact that I have written a large number of books and articles on the history of the Persian Gulf, and that a few of those concerned Bushehr in particular, including the more than 700- page history of Bushehr between 1797 and 1947. Also, these books and articles on Bushehr have been translated into Persian, and several Bushehris have written, commented and reviewed my books and articles in the local press. Finally, Bushehr is perhaps unique in Iran in that it has a local branch of the Boyad-e Iranshenasi and a very active group of people who are active in learning about their local history, including writing books and articles about it. Also, there is a daneshnameh-ye Bushehr (now already some 70 publications) that discusses all aspects of Bushehri history and culture, in which I have four to five contributions. Although of varying quality, this local interest and output means that, as I have noted during my last visits, when a speaker shows up, a large number of people attend such talks and engage in question-and-answer.

How was your recent trip to Iran and what did you experience? How did you find the country and its people this time around?

My recent trips, I have to say, because I was there in December and February, were great. My last visit was in 2005 and although the people of Iran have not changed Iran has. What struck me in particular was that the country had become Americanized (malls, fast-food, materialism, hi-tech, mobile phones) and that its people were probably the only ones in the Middle East that actually like the USA, not its policies or its government, but its people. It was also encouraging to see that some girls and women even shook my hands in public, and that they are taking an increasingly more important role in society. I was in several meetings that were chaired by very capable women. Just like in the USA there are more female than male students at the universities and I warned the audience of my talks that in the not too far future rather than a male-dominated society Iran would be one run by women, a statement that which instead of giving rise to outrage resulted in nervous male laughter. Also, compared to its neighbors, Iran is a rather ‘free’ country in that people have access to information, including from the US, and quite openly discuss politics, whether international or local, without fear of being branded a ‘counter-revolutionary,’ as in Turkey or in Arab countries. Otherwise, of course, I enjoyed myself enormously by seeing old friends, making news ones, hunting for books, and having interesting talks with faculty and students after my many talks.

In your studies about Iran and its people, what do you think are the best characteristics of Iranian people and the worst?

I don’t think of people, any people, in having best and worst characteristics. Having worked in more than 50 countries all over the world during my 35-year career, I have found that people, wherever they are, are not that much different. What they have in common that they all react to the incentives that they are exposed to, political, economic, religious, etc. For example, if I say that Iranians don’t plan very well, but are masters at improvisation, is that a best or worst characteristic? It all depends on the circumstances and I don’t think it is helpful to contribute to the proliferation of stereotypes of people. Just take them as they are and work with that and you will be surprised to learn that what is considered ‘best and worst’ was based on lack of understanding and empathy.

What is your best memory of Iran?

My favorite memory is one of my first visit to Iran in 1966. I was staying in Isfahan with the family of Dr. Morteza Sarraf, my Persian teacher in Utrecht. Now as you know, Iranians are a very social people and interaction is continuous and endless. Being less social than Iranians I wanted one day to be on my own. I closed the door of my room and sat down to read. After some time, Sarraf’s sister knocked on the door and opened it after I had given a sign of life and asked me: Narahat id? This question and experience was very important to me, because at that moment I learned more about Persian culture than I had gained from reading scores of books. It shows that exposure to other cultures, preferably not superficially, is important and educational, and very worthwhile as you learn not only about the other, but above all about yourself.

If you were to describe the Iranian people, how would you say describes them well?

I find this question very difficult. I can only say that I enjoy being in Iran and have interaction with its people. They are very pleasant companions, always ready to talk about any subject, even when they vehemently disagree with you. Above all, and returning to your earlier question, they are probably the most courteous and hospitable people that I know. I always feel embarrassed by the care, attention, interest even that people show for you. It is especially embarrassing when you are together in a bookshop and you want to pay for a book and you find that they either have already paid for it or very much insist of doing so, no ifs or buts about it. So, their boundless hospitality describes them well, so much so that I sometimes jokingly tell them: Mehman khar-e mizban ast.

You were born in the Netherlands. How was your experience growing up in Holland?

I was born in Utrecht, the Netherlands, a university town then of some 250,000 people. Growing up was a good thing and I am still doing so, be it now in the USA. In those days after the war, we did not have much, but we knew things would get better, so we were happy with the little that we had. I was and still am an avid reader, usually reading four to five books (not Iran- related) per week and I still go every Saturday morning to the public library to get my weekly share of books. What I do less is spending time with my stamps, which until some 15 years ago I did, as it is as restful as doing research on Iran. During my high school years, to make some money, I was a paper boy (delivering the morning paper at 4:30 am) and during the summer vacations, I worked in factories (usually night-shift as it paid more). During my university years, I worked for two years in a bar (on weekends – at night) and I had fun. So, nothing out of the ordinary, just a boy going from elementary to high school and, after a two year and two-day period of obligatory military service, then to University.

I know you are a tireless worker and are always doing research and coming up with new books. What are you working on now?

Yes, there are still a great many things that I don’t know much about, so there are plenty of subjects that I want to research and write about. At this very moment, I have just now finished editing the galleys of a book on The History of Khark, while after this interview, I will begin with the final editing of the translation of Kaempfer’s Amoenitatum Exocitarum, which will offer much new information to those interested in the history of Iran. I am also trying to finish the last chapter of The History of Kermanshah, while I have to write a number of encyclopedia articles, reviews, and finish an article that has been lying around for a while. In the second half of 2017, I hope to continue with a book on the History of Hospitals in Iran as well as a translation of Thomas Herbert’s Travels (first edition) into Persian, which I am doing together with Hasan Javadi, with whom I have translated already a number of other books.