On Sunday 3 September 2017, Kamal Foroughi turned 78, making him one of the oldest prisoners in Iran. Being a British citizen, one might have thought that Her Majesty’s Government would swoop in and cause a diplomatic furore for imprisoning one of its own. But after six and a half years in detention, the UK has been denied consular access, and insists its hands are tied because Foroughi also holds Iranian citizenship. The UK says it cannot do more if the other country does not recognise dual nationality as Iran does not, according to its own policy. But with the risk this potentially poses to hundreds of thousands of British nationals, should this policy be revisited and does the UK have the political will to do so?

Birthday wishes from afar

Following Foroughi’s birthday, his son, Kamran, organised a gathering outside the Iranian Embassy in London on 5 September to present a birthday card and light the candles on his birthday cake. In Foroughi’s absence, Kamran highlighted the injustices his father has endured. And Kamran told The Iranian messages he had for the governments of the UK, EU and Iran on this day:

“To the UK and European Union governments: my Dad is very old and the longest serving UK/EU citizen prisoner in Iran ever, with no evidence or explanation ever provided. We are living a nightmare. Thank you for your diplomatic efforts so far, but until Dad is back home safely with his family, you must do more to secure Dad’s release.

To the Iranian authorities: you have kept a 78-year-old man away from his children and grandchildren for 7 birthdays in a row. Dad desperately needs cataracts operations and prostate cancer tests, and he has been eligible for release each day for the last 1,340 days. Please reunite an old man with his family, before it is too late.”

Thanks so much @AmnestyUK & all supporters @Iran_in_UK for your birthday wishes #FreeGrandpaKamal another year gone! pic.twitter.com/Smya36iVII

— Kamran Foroughi (@FreeKForoughi) September 5, 2017

Some of the lovely #FreeGrandpaKamal cards & messages to be delivered to Iran embassy #London pic.twitter.com/11T8HqefMo

— Kamran Foroughi (@FreeKForoughi) September 5, 2017

Foroughi’s arrest arose in May 2011 when plain clothes police reportedly came to his residence in Tehran, with no warrant, and took him to Evin prison. In May 2013 he was sentenced to seven years’ imprisonment on espionage charges.

Foroughi was a businessman who was working in Tehran as a consultant for Malaysian oil and gas company Petronas. There is no clear evidence of what these spying charges involve. And the full verdict of his court case has not been disclosed.

Free Grandpa Kamal

Human rights groups have campaigned on Foroughi’s case insisting that he had an unfair trial. In addition the United Nations Special Rapporteur on the human rights situation in Iran Ahmed Shaheed as well as the EU, have called for Foroughi’s immediate release.

Now Kamran along with human rights groups are asking for clemency for Foroughi whose health problems have caused concern and who now needs cataracts surgery. According to Josie Fathers, Advocacy Officer for human rights group REDRESS,

“Under Article 58 of the Islamic Penal Code, Kamal has been eligible for early release every day since January 2014 (one third of his sentence). There’s been several instances where the Iranian authorities have verbally indicated that his release was imminent and his lawyer has made over 50 applications for his release, but these have been met with no reply.”

Foroughi’s medical examination results have been awaiting collection in Evin prison for over a month now, which no-one can seem to access. Foroughi has no family members in Iran and has been denied consular access from the UK’s Foreign & Commonwealth Office (FCO).

Are the FCO’s hands tied?

The FCO did not respond to The Iranian when asked to comment on their policy towards dual nationals and the efforts they are taking to free Foroughi. But they have previously responded to Foroughi’s case in the following way:

“The FCO have been aware since 2013 and provided assistance to the family but it has not been able to provide consular access to Foroughi because Iran does not recognise dual nationality and treats him as solely Iranian.”

In 2017, however, with other UK-Iranian dual nationals like Nazanin Zaghari-Ratcliffe and Roya Nobakht imprisoned in Iran, some see this line as inadequate.

That’s why Labour MP Tulip Siddiq who sits on the opposition benches of UK parliament, recently held a debate in the House of Commons on the issue. Former and present Prime Ministers along with former and current foreign secretaries have said they’ve raised the case of Forougi, Ratcliffe and Nobakht with their counterparts; however, they have not publicly condemned Iran’s actions, nor have any of them met with the families.

“That is something the families have raised with me over and over again”, said Siddiq during the debate on 18 July, “Why will the Foreign Secretary not meet with the families? Let me be clear: we do not doubt the sincerity of the Foreign and Commonwealth Office staff, but the fact is that this is not working. The Foreign Secretary needs to meet the families…”

And acknowledging the wider crackdown on dual nationals in Iran, Siddiq said that there was a need to review “Government’s broader policy towards dual nationals who are detained abroad”, saying, “If we accept the status quo, we are accepting that the way Nazanin and Kamal are being treated is okay. That is not acceptable for many Members of this House…”

The Minister of State for Middle East Affairs Alistair Burt responded to calls for more action by insisting that FCO staff are doing what they can. But their stance on the nationality issue remains the same:

“Unlike the UK, Iran does not legally recognise dual nationality. It considers our detainees to be Iranian, which has implications for consular assistance, which are set out in the passports of those with dual nationality. Under international law, states are not obliged to grant consular access to dual nationals, which is why our passports state that the British Government are unable to assist dual nationals in the country of their other nationality”.

Burt also said that what was in the best interests of the prisoner hinged on their relationship with Iran. Burt said, “I am hoping to take the opportunity—and I am sure the Government are hoping to take it—to explore what this new chance of a relationship with Iran means, both for us and for them”.

A new policy

But Siddiq was concerned about this approach, “Families cannot be left in the dark about the framework of work that exists when their relatives are treated in such a way. A Foreign Office approach of discretion encourages inertia, but also defines the kind of foreign policy that the Government are mandated to deliver.”

But as Siddiq suggests, the UK policy can develop. For instance, the UK can address the gap in protection for dual nationals. Or where Iran has breached the Vienna convention on consular relations it can bring cases before the International Court of Justice. And it can make complaints if breaches continue.

And Siddiq has taken this a step further by drafting and submitting a Ten Minute Rule Bill, which would give FCO officials the power to take a stronger approach with disclosure to the families if it is approved.

Whether the UK government is doing all it can to do what’s best for British prisoners in Iran, is difficult to assess. But what is clear is that Foroughi and other UK-Iranian dual nationals in Iran’s prisons are falling through a protection gap. And human rights groups don’t believe there is a compromise on what the UK should be doing to protect its own citizens, despite not receiving consular access.

Time to act

Amnesty International Researcher on Iran Nassim Papayianni told The Iranian, “The UK Government should still raise their concerns for their nationals at every opportunity with the Iranian authorities. If they continue to hold the Iranian authorities accountable for these unjust cases, then it would be more likely that the circumstances of British-Iranian nationals languishing in prison in Iran might change.” She also believes this was why Foroughi was afforded more access to medical treatment. But Papayianni also pointed out that they should speak out publicly, not just pursue diplomatic routes.

Fathers reiterated this position, and said the UK government should be insisting “loudly” on immediate consular access for Foroughi, Ratcliffe and Nobakht:

“The UK has not been able to obtain consular access to them due to the fact that Iran does not recognise dual nationality. The UK should not accept this position, and in cases such as this where there is a pattern of denying consular assistance, they should bring them before the International Court of Justice to gain access to them.”

UK and Iranian relations have improved since the Iran nuclear deal, but the relationship between them is still marred by a history where suspicions have run deep. And alongside Iran’s complex power structure, Burt isn’t completely wrong in pointing out that achieving outcomes for British prisoners in Iran may take time.

At the same time, however, there are inconsistencies in the UK’s rhetoric. The current Conservative government claims it cares about the human rights of dual nationals from the UK. But human rights have notably taken a backseat in other cases. The Foreign Secretary Boris Johnson has openly said for instance that the UK doesn’t want to upset its relationship with Ethiopia, hence why it does not intervene in the case of British man Andrew Tsege’s, a political prisoner in the country. It has also refused to stop selling arms to Saudi Arabia, accused of human rights abuses in Yemen while using British weapons. These examples are different but it speaks to whether the current government has the political will to address its protection gap when human rights have not exactly been paramount.

Both Iran and the UK would benefit from a better relationship, economically at least. But the Iranian diaspora in the UK are key to building those links as well.

With 600,000 dual nationals in the UK, the government should think more wisely of instilling their trust, they are a good proportion of their electorate after all. As well as the mobilised public who have signed petitions to see Foroughi and others released. If consular access is the sticking point, perhaps that’s where the UK should start amending its policies.

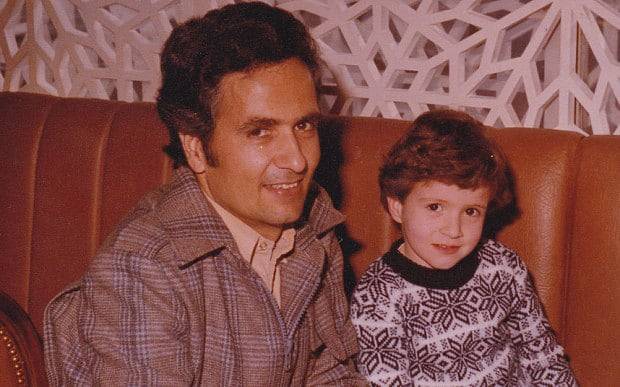

Cover photo: Kamal Foroughi and his granddaughter