The body who invaded my life The body who invaded my life

Part I

Part

II

By Reza Ordoubadian

July 7, 1999

The Iranian

Believe me when I say I am not exaggerating at all. I admit: I

can lie like the best of you, but I am simply putting down what

he told me in his own words; of course, I had to rearrange the

events and chronology because he talked so fast and jumped from

event to event without giving a time frame or sequence. I have

done all that for you, and you need not spend time gluing the events

together to make sense of what he said in his confused way.

However,

I assure you, these words are his, only in translation. He spoke

in Farsi and Azeri, both of which I know well, but the way he

switched between the two made understanding even harder. It is

a relief

to write in one language - with continuity of thought and events.

I am not claiming everything is a miraculous rendering of what

he told me; there were gaps that I had to fill in to make the

English text available, because in those languages indirection

is an art,

and making straightforward statements a dangerous game of hide-and-seek.

I guess it has to be that way: they have been, throughout their

history, subject to so many wars that they had to develop an

elaborate code system to avoid disaster, codes that they understood

- codes

that give a translator fits. Moreover, they lay claim to a

mystical source in their lives that for rational people will sound

spooky

and illogical. I have tried to soften the hazy edges of the

events that bordered on such naive notions, but I am not sure I

have

succeeded much.

To make the matters worse is the fact that he, the man servant,

is only an intermediary: the man who narrated his story to him

has disappeared, or at least that is what my source claims, but

knowing what I know of the culture of the region, I have no doubts

about the accuracy of the statement.

"Cy just took off; he left one day and never came back, his

twin sister having fled earlier," he said with his eyes vaguely

looking nowhere through the window in his small room. "He

said he will not be back until the jonquils blossom in the spring

after the new year - but time is so confused nowadays that I have

lost count of the days, even months, and don't know when the spring

will come or that the jonquils will ever blossom. I only hope they

do because I have a feeling that my own life will be quite empty

without his coming back to set it right."

Then, here is Cy's story as he had narrated it to his one-time

man servant-after four different translations and a year's constant

work at editing and finding the right words with the help of six

dictionaries and a number of consultations with lexicographer here

and in England.

****

He just appeared at the door and rang the bell, not with an intermittent

pressing of the button, but with a continual, shrill sound that

rang through the house - a terrible noise. I was the one who opened

the door: there stood a short, slight boy of perhaps fifteen years

of age: eyes, the shape of large, black circles; face, moon-pale

and round; hair, long, jet-black strands that curled around his

head and gave the feel of a black halo circling his head in an

oblong shape, rising from the back of his head to the upper part

of his forehead. He smelled of pine trees, perhaps having slept

the previous night in the open on a soft bed of pine needles, natural

and wild.

"Your father in?" he asked with a sweet voice that was

demanding for his age and slight body, my age, but not my body.

"Yes!" I replied crisply and stood still, filling the

open door with my body, in silence. Not that I was out of words

- I just could not find any words to match the silence. In a peculiar

way I felt in awe of the boy, which irritated me. After all, I

was bigger, much bigger and stronger.

"I want to see him," he said with the same commanding

voice, unfazed by my stubborn, threatening silence.

He said that and walked right inside the entrance hall; I do not

know how because I was just about filling the doorway solid, but

the fact is that he was inside, and I was still blocking the doorway.

However it was, he had passed me by, by trick or sleight, but I

suppose he was so slight himself that he could pass through me

somehow without my noticing it.

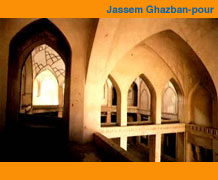

He walked the distance of seven meters from the door to the steps

in the middle of the entrance hall that ascended to the second

floor. Two columns on each side braced the staircase, forming two

passageways on either side, narrow but frequently used, leading

to the back side of the stairwell, where a large, two-panel door,

exact replica of the entrance door, opened to the main body of

the house in the first floor, to the several hallways that led

to the living quarters of this old, languishing house, built by

my great great-grandfather in the middle of the nineteenth century.

The house - better call it a mansion - had at least twenty-one

rooms and three wings. The outer wing facing the boulevard, the

noisy front side, lined with ancient oak trees in four rows, was

used mainly by the servants and the household crew.

The boy hesitated in front of the stairway, but chose one of the

side passages to go to the back of the house. As if he knew the

lay of the house, he opened the door and crossed the first corridor

and was soon in front of the living room where my father was working

on his papers.

Why did I stand still and did not object to this intrusion I have

never understood, but the fact is that I stood there momentarily,

hesitant and lost, then followed the boy to my father's room, not

resenting the fact, but totally immersed in the process; I was

playing a game or acting on a small stage to fully complete the

drama, where the actor has no choice but to utter the words written

for the role and act according to the prescribed stage directions

- a puppet.

The boy entered without knocking on the door; my father raised

his head from his papers and looked at our direction, his pince-nez

just sitting at the hook of his nose at the larger end. He did

not seem irritated at the intrusion - as he normally did when we

interrupt his work, which was nothing more than signing a few documents

to be executed by his emissaries. I forgot to tell you that he

was a prominent man of wealth and not much work, all inherited

from his father who had inherited from his father for generations.

One might call him a true aristocrat who had the leisure not to

work, but enough work to claim a day's labor without working.

"Sorry," I started to apologize - for what, I cannot

tell! But the boy moved forward, and my father's slightly raised

hand to silence me froze in mid air. He lowered his head to look

above the lenses with his piercing eyes that often gave me nightmares

- they still do long after his death.

"You're Mister Ka'mal?" the boy asked.

"Who are you?" My father inquired, not with his usually

overbearing voice, but with a very kindly tone.

"I'm Raheem. You must remember me," the boy replied,

emphasizing the word "must."

Father removed his glasses, rubbed his face with his right hand

as he thought for a fleeting moment, but I could see there was

no sign of recognition on his face. The silence was now terrifying.

I wanted my father to deny and send the boy away, but he just looked

at the wall, above where the boy was standing, gazing at something

that wasn't there. What was he thinking about? I wanted to know,

and I wanted to know the connection between the boy and my father.

Neither seemed to know the other, yet there seemed to be a connection

between them that I wanted to know.

Perhaps, not: I really did not want to know that - all I wanted

to do was to push the intruder out of the door and get rid of him,

but I did not dare because my father was the boss of the house,

and no power-play was possible under his roof. In desperation,

I moved further inside the room and stood by the window that opened

to one of Father's walled rose gardens, a symbolic gesture to put

distance between myself and the boy-physical and psychic.

"I suppose you want to stay here," Father said tentatively,

quite uncharacteristic of him. He was always sure of what he did,

even when he was wrong. This equivocation was quite unsettling.

"Yes," the boy replied firmly. No "thank you," or "please," or "if

it pleases you, Sir." Simply, "yes!"

Father barked an order, and a man servant appeared at the door.

He bowed with his head slightly lowered, really a nod, but remained

silent. No one spoke in our household unless he was addressed directly

by my father first. Another short silence, heavy and terrible.

I wanted to fight the boy, to beat him up and then throw him into

the street. I wanted to say, "You have no place in our house,

go away to your own kind," but no words would escape my lips,

and I remained silent, choking with my own unuttered words. Now

that I think of it, I had no base to despise him so intensely,

so unreasonably, but I did hate him more than I hated anyone, including

my father.

"Take Raheem to a room in the outer corridor; he will live

there." Then as an after-thought he added, "but he will

eat with us!"

That was the final draw; the boy was being treated like one of

the family; did he have more claim on us than we knew? And, it

was not his fault - I thought of it even then. It was my father

who was letting in a vagabond to interrupt our peaceful life, a

boy who was no kin to my family: and Father was doing this only

six months after my mother's sudden death. He could have said "stay," but

Father distinctly said "live there," giving finality

to the boy's intrusion. And, "eat with us!"

"Just a change for him, Cy," my sister later tried to

offer a reason for it all.

"Change! Change from what to what?" I shouted, away

from Father's hearing. "He's inviting a dirty street boy to

come in and be one of us!"

"A change, you know! After Mother's death and this damn revolution

raging outside. You're making too much of it - he is really a very

nice boy."

My own twin sister was now turning on me, siding with that infectious

bastard, who could be my father's bastard, but was not, as I learned

later.

***

So far as I was concerned, Raheem lived like a stranger among

us, but was welcome to everything we had. Even I grew to hate him

less as we started to keep company with each other - on Father's

strict instruction, of course.

A month to the day that Raheem made his move to live with us,

Father died of a heart attack, just as both my grand-father and

his father had died of heart attacks in their mid-fifties; and,

the revolution did not help my father's already weakened heart.

Since I was the oldest male child, I had the burden of dealing

with all the arrangements for the burial and legal affairs: for

the first time in my life, I was in charge. We had, of course,

several lawyers to help, but the most helpful aid came from Raheem,

who plunged in like a family member, even wearing a black band

on his left arm to mourn the death of a close family member. I

still don't know how, but before we made our moves to do anything,

Raheem had the official death certificate from the Ministry of

Justice, had engaged the crew of The Burial Bureau to move in and

get the body to the cemetery for burial, a miraculous act because

the Bureau is known for their deliberate delays until someone delivered

them their customary bribe so that the body was moved before it

smelled. All this work without spending a penny, or, that was how

we decided because Raheem could not have found enough money in

his pocket to buy a piece of American chewing gum, and we certainly

had not given him any money to bribe the Chief of the Bureau.

The body was moved the day after Father died according to the

religious ceremonies prescribed by the Prophet - or, so I was told

- a bearded cleric reciting the Death Prayer all the way from our

house to the cemetery, ten kilometers away. Raheem saw to it that

the prayer was said continually by sitting next to the cleric in

the lead car, Father's own black Cadilac - now, mine. I was told

later that, when the man tried to take a rest, Raheem reminded

him that he had not been paid yet and that he would deduct a certain

amount of money for every minute that the man remained silent!

Raheem also solved the main obstacle on the way of Father's burial;

the times were bad; the seeds of revolution had already been sown,

and streets were filled with young and old, men, women, and children

our age, mostly dressed in black to commemorate the death of one

of the revolutionary leaders in the north. The traffic had been

snarled for a week before we sent Father to his resting place,

and the prospect of moving a caravan of mourners through the crowd,

exuberant revolutionaries who wanted nothing less than the demise

of the king, seemed impossible, especially with the ostentatious

revere with which we planned to dispatch Father to his Maker. At

one time my sister and I had thought of hauling the corpse in a

helicopter to the cemetery, but the government objected because

they feared an overhead helicopter might be taken by the crowd

as a provocation, a spy flying overhead to take their pictures.

Under the circumstances, that would prove fatal to the government's

attempts to negotiate with the revolutionaries who, in my mind,

made up the majority of the country. Perhaps if Raheem knew of

our plans, he would arrange something, but that was basically my

plan, and I would not have him share with what I had thought of

myself.

Raheem put a large, green flag on the hood of the lead car - green

being the color of the descendants of the Prophet - and since the

revolution had basically been started by the cleric, those who

were mulling in the streets, even those who belonged to the Communist

Party, out of deference to the Prophet, opened a passage way, like

the sea parting for Moses, and our procession moved with a dignified

speed to the cemetery, and we buried Father in his grave, next

to the marble - covered grave of Mother and our other ancestors.

Thank God, the ceremony lasted only a short while, but Raheem was

no where to be found, and I still do not know how and where he

got out of the car and disappeared into the crowd. It was not until

late afternoon of the burial day that he finally showed up in the

house, not sad, but cheerful, not somber, but delighted by all

the events of the day - of the weeks since he had forced his way

into our lives. I also knew that since I was the head of the family,

and he lived under my roof now, before long I should ask him to

leave us and find his fortune with another family, but I did not

know how I would broach the question. Would I say, "Just take

your coat and leave!" That is all he had brought to my house.

Or, "Now that Father is gone, you better find another place

to perch!"

Nothing of the sort, because when I approached my twin sister

to plan a way of getting rid of Raheem, she was adamant that he

stay on for as long as he wanted. "He is one of the family," she

said with a seriousness that really was demeaning to me. "He

made all that procession to work - Father would still be here if

it hadn't been for Raheem."

"He is a pain in..." I tried to reason,

but my sister would hear nothing of my decision and insisted that

the subject should be dropped, at least until the Forty(*).

Knowing how stubborn my sister can be, and frankly feeling grateful

to Raheem for what he had done, I dropped the subject until the

Forty.

Raheem did not need any instruction; he stayed in his room and

seldom came to the back of the house any more, as if it was my

father who had been the object of his attentions - and needs. He

remained in the front section of the house, and I would occasionally

run into him when going out or coming in, as at that time we still

used the front door for that purpose. Raheem, however, had grown

wan and very tired looking. He still had that angelic smile on

his face, but he did not care to talk or communicate with any one

except the man servant who had initially shown him to his room.

A week after the burial all pandemonium broke. The revolution

was in full swing and the streets were being occupied one by one

by the revolutionary armies. The king fled the country, fearing

for his life, but promising to return soon. That would not happen.

An ecclesiastical government was declared in the land, and orders

were sent for all the people to dress properly, according to the

religious laws, abstain from drinking alcoholic beverages, pray

their prayers and be decent and calm under the new regime of One

God. But it did not turn out that way, not exactly! As each group

of the revolutionaries occupied a certain street or area, they

set up their own laws and their own system of punishments so that

the new government was helpless to deal with all the mini-dictatorships

and self-proclaimed ecclesiastics. Our area was occupied by the

group who called themselves The Slaves of God, which was headed

by a twenty-two year old ex-convict during the king's time. He

demanded and was afforded anything that he wanted, a naive dictator

in charge of life and death. He ordered plundering of the property

of those who were suspected of sympathizing with the previous regime.

All around us, buildings were pulled down and people killed or

tortured. But nothing happened to our house, not even a messenger

came to demand food or money for the revolutionary forces of The

Slaves of God.

"You know," my sister mused. "I bet it is Raheem!"

"What is Raheem?" I asked absentmindedly.

"Us - nothing is happening to us."

"Well!" I said, dismissing any ideas that she might

have about Raheem's forestalling any harm to come to us.

"Admit it!"

"Admit what?" I raised my voice. "Do you really

think he's one of them? Working underground, but protecting us

for his own benefit?"

"You don't understand. I'm talking about the other thing

we were discussing yesterday!"

"A miracle!" I said. "Do you really think that

Raheem is an angel, a supernatural body, come to help us exclusively?

Make up your mind, Sister: Devil or Angel?"

"Why not?" she asked quite seriously. "What's wrong

with Angel? You have all but abandoned him, the way you ignore

his presence and practically show him the door. Is that right,

after all he has done for us! He hasn't come to the back of the

house in three days, just keeping to himself in that room."

Why not, indeed. I do not believe in that stuff, anyhow. "I

felt very strange this morning coming through the passage on the

left side of the staircase," I continued, hoping to change

the subject. "I don't know what it is, but I felt claustrophobic,

jammed in - that sort of stuff!"

"What?" my sister jumped, annoyed at my attempts to

change the subject from Raheem and his miracles.

"Well, Sister! Either I have gained quite a bit of weight

in the past three weeks, or the passage is getting narrower," I

said, and I was not joking!

My sister stared at the ceiling for the longest moment, then slowly

lowered her head to meet my eyes, straight through, and said, "You're

right: I had to move sideways to pass through the passage. What

do you suppose is happening, Cy?"

I had no explanation: the fact was that I felt each day the passages

on the sides of the stairway narrowing, a small amount, but still

discernible. I used to go through those passageways easily, at

times my sister and I passing through together-side-by-side. But,

since Father's funeral, the passages were narrowing, simple and

a fact. None of that appealed to me; I could not, at the age of

fifteen, imagine any cause that could affect that result. It simply

did not make sense and should not be.

"Nothing - just our fertile imaginations!" I grumbled

under my breath, not just to appease my sister, but also to confirm

to my satisfaction that all was a matter of perception, and nothing

more.

But it was more than just "fertile imagination." There

we were, two young people who had the same experience with the

passages. The last time I had gone through one was the same morning,

and that seemed a century ago. "Let's go together," I

suggested. "Let's both see if that is so together."

My sister jumped to her feet. "Yes!"

We walked the long hallway to the back of the stairway where the

two-panel doors shut the front from the back, and I tried to open

the door, not suddenly, but with cautious hands, unhurried, hoping

to postpone the encounter as long as I could. She sensed my hesitation

and pushed the door out. There was nothing extraordinary behind

the door because it was dark except for two narrow slits of light

that came from the two sides of the stairway. That wasn't right,

I thought. The sun was shining outside, and normally the two passageways

would be lit with the bright light coming from the glass panels

of the huge entrance door. I switched on the light: it was like

a tomb lit by a single, faint candle.

I moved to the left passageway and my sister went to the right.

Unless I were transformed into a two dimensional cardboard dummy,

I could never pass through that slit, the only opening left from

the passageway.

"It's all shut closed, Cy," my sister whispered, as

if some one could hear us, someone who was in charge.

"My side, too," I whispered back.

***

It has been five weeks since we encountered the shrinking passage

ways. They are now completely shut closed, and no traffic is possible

through them. We have to use the back door, which is on the far

side of the building, to leave the house or enter it, a door that

had not been used for almost seventy-five years. The door is a

humble opening with only one panel made of solid oak and no glass

panel to let in light, nothing distinguished about it like the

front door, with magnificent columns and two large panel doors

that when opened, a truck could drive through. There is a mustiness

about the back door, which is disturbing and consoling at the same

time. The front door has been changed several times during the

life span of the mansion, but the back door remains totally solid,

never changed, which gives it a sense of continuity and comfort.

I suppose that is what is consoling about it.

We have not seen Raheem since the passageways closed shut; my

sister claims to have seen a light in the front room where he lives.

I am not bothered by him any longer because he is completely out

of my life; besides, the army of The Slaves of God have reclaimed

the back part of the mansion, and we are to leave and go to our

summer home up north. I do not know when we will come back, if

ever. Perhaps, when the daffodils blossom, once again we will find

a new door for the front of the house and reopen the passageways;

but Narcissus will not blossom this year because of the severe

winter that has killed all kinds of flowers and living things >>>

See Part II

Note

* Forty days after the burial, a ceremony to end the immediate

mourning until the Year, when after one year of burial mourning

officially ends. BACK TO TEXT All copy rights are reserved by the author.

Author

Reza Ordoubadian holds a Ph.D. degree in English and linguistics.

He has held a professorship at Middle Tennessee State University

and Visiting Professorship at Umea University (Sweden). He has

published numerous pieces of fiction and poetry as well as scholarly

articles and books on both sides of the ocean. He was the editor

of SECOL Review for 18 years.

* Send

this page to your friends

|