Alive in Kabul Alive in Kabul

I have experienced here a feeling

that is not as common these days as I'd like, and it is hope

By Roozbeh Shirazi

June 21, 2004

iranian.com

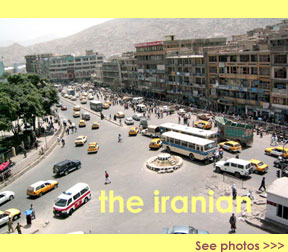

For the next few weeks, I will be living and working in Kabul,

Afghanistan. I was drawn here for many reasons, some professional,

and some personal. Regardless of the reasons, I believe that this

experience will not let me leave the country unchanged. Built and

named after the site of a small straw bridge that once stood here

long ago (Kah Pol, or Straw Bridge) modern Kabul does not seem

to have glamorous parts; many of the buildings are in ruins, half-built

or half-destroyed, I cannot tell >>> See photos

Still, my colleagues told me that at least in the airport, there

seemed to be greater stability and more order than the last time

they were here, though the queue at the customs office suggested

anything but that. Conspicuous foreigners were picked out by Afghan

customs officers or by the Canadian soldier who patrolled the terminal

to a special line, including two of my coworkers and Geraldo Rivera,

with whom I had a brief and interesting conversation. To

my delight and later social benefit, I was not easily identified

as a foreigner, and so remained in line avoiding the clamoring

luggage porters working the foreigners.

Foreigners are everywhere. Germans, French, Americans, and others

have opened schools and other development projects here and there

is a visible and vibrant aid-worker culture in Kabul, complete

with some leafy green

hideaways where one can have a pizza, drink

a beer, and hear young ex-pat idealists and cynics trade stories

and come to similar conclusions; being in Afghanistan is intense.

I am here to work with the Ministry of Education on literacy

curriculum development through UNICEF and my school. Looking out

from the

window of the Ministry of Education five floors above, the streets

of Kabul look alive. People, cars, buses, and carts noisily and

seamlessly weave through each other, miraculously defying death,

collision, and chaos in the absence of traffic lights.

The main

thoroughfare looks like DNA coiling as U.N. SUVs, taxis, and buses

double helix through each other on their way to nowhere. A loud

speaker blares the traffic police's ignored directives while

drivers load and unload their passengers and cargo seemingly anywhere

they wish, including in the middle of the intersection. Everything here is the color of dust, even the trees blend into

the landscape of soft browns, tans, and yellows. Streets are walled,

giving homes the privacy desired to act as one wants. Occasionally

you walk by an open door and meet the eyes of someone you are

not intended to look upon, or see a splash of violent green

from gardens and grapevines in these courtyards. Women no longer

universally wear the burka, but the infamous garment has far from

disappeared-I have yet to see a woman's head uncovered outdoors.

Most of the women you see outside appear young. Men walk hand

in hand under gigantic posters of the late guerrilla leader Ahmad

Shah Massoud, the heat of the

sun is dry and exhausting and even the fruit in vendors' stalls

look thirsty. Absent from schools, children here sell cigarettes,

newspapers, offer

to weigh you, and even volunteer to serve as

your guides and guards.

Assault rifles are as common here as cell

phones are in New York City; I have counted over one hundred

in the week I have spent here. The lack of Western bathrooms, and

with them soft toilet paper and other luxurious goods are but

a

small part of all the things here that make you realize that

your American shit does indeed stink, and seeing your life's privilege

here humbles you.

This city is alive, congested,

and somehow still cosmopolitan despite 23 years of war, bombings,

and strict curfew. Much of the

city

has been carved into the mountains running through it, which

has the effect of making Kabul stretch endlessly into the horizon.

Long and heavily guarded convoys of soldiers

in armored vehicles steam through town; they are the only ones who look unhappy

and tense to me.

Though the movement of foreign workers is restricted, I have

had some opportunities to see Kabul beyond the panes of automobile

and building windows. One does not get a sense of conflict and

strife walking through the bazaars of the city; vendors hawk their

wares against the sounds of Indian

pop music, Googoosh, and traffic

from the street. Kabobs, spices, doogh, and piles of fresh bread

all capture and dazzle your eye as you walk through the street.

People have been only friendly, and very welcoming to me, happy

that I speak Farsi well considering that I was born in the United

States and do not seem to have ulterior motives for befriending

me.

To me Afghans seem more straightforward than Iranians,

and have a great penchant for spontaneous laughter in our conversations,

to an extent caused by my mistakes when speaking Farsi. Still,

making mistakes is the best way to learn from them, and I feel

my Farsi improving dramatically because I have had to translate

abstract concepts and professional terminology, forcing me to have

to make culturally appropriate analogies to convey my points and

purchase a Farsi-English dictionary for when I don't. My Afghan colleagues challenge and inspire me - the UNICEF team

has come to help them develop new textbooks and pedagogical practices,

but it is me who is learning so much in my discussions with them.

We have different opinions about how to achieve certain objectives

and often our most emphatic points are lost in translation, but

we share the goal that these materials should be reflective of

Afghan ideas and culture, not prescribed from outside, and help

move the country forward from its turbulent past.

It is too early for me to say what I feel or how I think about

the country, but I can say the conversations I have enjoyed the

most have been with a young Afghan colleague of mine at the Ministry

of Education who is my age and lived in Iran for twenty years before

returning to Afghanistan. We enjoy discussing the differences between

Afghan and Iranian cultures, the similarities of our histories,

and stories of each other's childhoods. Most of all, we have

discovered despite our different personal histories, we have a

talent more making each other laugh, and we are making our relationship

more personal and less formal.  I have experienced here a feeling

that is not as common these days as I'd like, and it is hope. Despite

the setbacks, the political

intrigues, the unclear role of coalition forces in stabilizing

the country, despite the violence, poverty, and limited resources

for continuing our work, I have hope that things will improve. I have experienced here a feeling

that is not as common these days as I'd like, and it is hope. Despite

the setbacks, the political

intrigues, the unclear role of coalition forces in stabilizing

the country, despite the violence, poverty, and limited resources

for continuing our work, I have hope that things will improve.

Over the last few days, different people have asked me here what

Americans think of Afghanistan and what they want to happen here.

I have told them that there are many opinions among the American

people, and it still was not clear to me what America ultimately

wants in Afghanistan.

Sitting down and writing this a few days

after those conversations, I hope that Americans will understand

we have a responsibility here, and it is not to tell these people

what to do or occupy their country; it is to enable them to rebuild

and restore their homeland. And I hope that, upon understanding

that responsibility, that the citizens of the United States will

hold their government accountable for its actions >>> See photos

.................... Say

goodbye to spam!

*

*

|