Inside a different city Inside a different city

Five weeks in a refugee camp in Lebanon: Part

8 (last)

By Sina

Rahmani

December 24, 2003

The Iranian

The Stronger Sex

With the fall of Afghanistan's Taliban regime,

filmmakers, writers, journalists, and aid workers came to expose

the plight of Afghanistan's women. They spoke of the harsh laws

placed on women that banned them from working, forced them to

stay in their homes, and, most shocking, forced them to wear

the burqa.

To the "liberated" women of the West,

the site was a shocker. In the immense heat of Kabul, here were

these poor souls

who were forced to cover themselves from head to toe. Suddenly

the phrase "lifting the veil" became the buzz words among

media and aid workers. Of course, the plight of Afghanistan's

women was terrible and an affront to all peoples who have souls.

And of course, no woman should be forced to wear anything that

go against her personal wishes.

But among all the good intentions,

there was a more sinister undertone in the notion of lifting the

veil: it was the duty of the West (read: white people) to liberate these people (read: non-white people,

in this case brown) from the backward ways (read: Islam). It was

the duty of the West to liberate these people from their brutal

rulers as to impose its own cultural mores and understandings.

(George W: It is our duty to share the democracy that God gave

us (although it was the Greeks who gave us democracy))

One

documentary I saw was particularly arrogant -- a Canadian woman

walked around the streets of Kabul interviewing people and lamenting

at all the work SHE had to do. I thought at the time that if this

woman cared so much for the plight of these women, that she would

put down the camera and donate the money that covered the absorbent

film costs to these poor women. The idea never came to her

that she should pursue Afghani women who were making a difference

and proceed to help them--only the notion of the Westerner arriving

on her silver horse to solve all of their problems.

Although there

is work to be done in exposing matters of social injustice to the

outside world through cinema, documentaries like the one mentioned

above only further

the notion of the weakness of the women of the Arab/Muslim world.

She is the veiled woman who cries over the death of her fanatic

son, calling for revenge from God. She is the woman who hobbles

along the dirt road holding her grocery bags. She is wrinkled and

old, never radiating any beauty, only a sadness that causes the

viewer to think: "Ahh. Gee. She has it rough."

Most importantly,

there is a weakness in these women. But listening to the stories

of the women

I have met in the camp, one realizes that Muslim/Arab women are

some of the strongest and most courageous woman in the world. This

strength only comes from successive generations of colonialist

expansion, war, civil unrest, and persecution. There were the Iranian

women who marched in the streets of Tehran, (a famous picture of

an Iranian woman lighting a cigarette with

a Kalashnikov in the other hand). There were the Algerian women

who helped revolt against the French during their struggle.

Palestinian

women have been a notoriously raucous group. During the Intifada

of 1987-1991, Palestinian women were always protesting, organizing,

and drawing international attention by speaking so eloquently through

the likes of Hana Ashrawi. Palestinian nurses were always on the

front lines tended to the fallen men and were known for their abilities

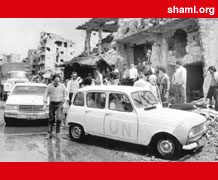

to make due with very few resources. In Lebanon during the Civil

War, with continual sieges and bombing campaigns, their role was

that much more pivotal.

But the stories are not all so heartwarming. During

the massacre at Chatila camp and the neighborhood of Sabra, doctors

and nurses

were hunted down and killed by the Phalangists forces. Olfat Mahmood,

now running an NGO in the camp, was a nurse at Sabra hospital,

and survived the massacre by jumping from a window. Women, especially

the Palestinians in the camps, were targeted by various factions

to send a message to the PLO and their supporters.

The pressures of war life are intense. The responsibility

falls to the women to keep the

fighters and the non-combatants in the camps fed. Often, food would

consist of a boiled onion or plain Thyme, and this would

often feed families with dozens of members (It was during these

sieges that conditions deteriorated so much that families

proceeded to eat the various animals wandering the camps).

In Arab

countries--especially the agrarian Palestinian culture--the role

of the mother as a caregiver is particularly strong. The ability

of a mother to tend for her family is the prime source of pride

and joy for any woman in the camp. The inability to do so often

drove many women into depression (and suicide), which they still

live with today.

Even before the Civil War, women often had to burden

the pain of camp life. When the camps were set up, Lebanese soldiers would patrol

the camp and, since they preferred not to have to walk through

any water, people were not allowed to use water during daylight

hours, as it might spill into the pathways. Women would wake up

before dawn and do the cooking and washing for families with multiple

children. Hands had to be washed only at night and baths taken

in the dark.

All this had to be done among constant power outages

and a complete absence of clean drinking water, both of which have

continued to this day. For instance, there were 12 power outages

today, apparently as a result of a decision by the Lebanese authorities

to lower the electrical allowance of the camps.

The pressures of

camp life aside, there are the patriarchal overtones of Palestinian

culture. Men are the important people here, and thus, theirs is

the only voice to be heard. Men control the finances and thus effectively

control daily life. Divorce--that is a woman divorcing her husband--is

unheard of in the camp, thus making bad marriages inescapable.

One woman in the

camp who has been particularly kind to me, lamented to me about

this when I asked when I would meet the rest of her

family. "My husband, you won't meet him. He is out with

his bitches and I don't care." When she sees the apprehension

on my face, she apologized. "I get this way when he beats

me."

But, like all vestiges of anything Palestinian, life

goes on. Children get fed, jeans get mended, and scrapes are properly

bandaged. And the kindness continues: when she finishes putting

dinner out for her three kids, she asks me: "Sina, I know

you must hate falafel by now. I made you a few vegetarian dishes. Take them home and eat

them. If you want more I would love to make some more. Have you

done your laundry yet? Just drop it off tomorrow. If you don't

I will be very angry at you. How is your film going? I have organized

a meeting with you and some people, they would love to speak to

you and be in your film. I will translate."

Between Them and Us

"That girl over there, she is a bitch."

My head turns away

from the group of girls that were giggling at the weird foreigner

with the weird hair and clothes. I look to the young man who

made the comment.

"Why?" I seem to be the only

one who doesn't know. "She has sex."

I am baffled by his response.

A few minutes ago the guys, including this specific one, were proudly

parting

to me their respective sexual histories. I refrain from challenging

him and I try to change to topic, not wanting to learn more,

to no avial. They keep going.

Turns out most of the guys in the village, a predominately-Christian

town of Kaftoun near Tripoli, are familiar with the prostitutes

of Lebanon. I hide my shock, unused to notion of prostitution

being a worthy source of pride. Although most or all of their

boasts could have been exaggerations or plain-macho lies, I

come to the realization that prostitution in Lebanon is accepted

in the

male-only circles of Lebanon. "Russians, Syrians, Fillipinos,

Palestinian, Lebanese--anything you want in Lebanon," another

one in the circle says to me, as if presenting me with a menu.

Although they never proceed to ask me directly if

I want to patron one of these girls, I definently get that impression.

My suspicions

were confirmed later on that night when my friend I was with

told me that they wanted to ask me, only to be turned down,

thankfully, by my friend.

The experience was an albeit sobering awakening

to odd sexual dynamic at work in Lebanon. Beyond the double standards

placed

on women, which happens everywhere in the world, I get the

impression that this is a repressed society--not just politically.

"The

problem with the girls in Lebanon is that they lead you on.

They go out with you and then they never let

you sleep me with

them," my friend says. Although, I am tempted to ask whether

he has met and dated everyone women in this country of three

million,

he proceeds to tell about his sexual failings with Lebanese

girls.

There is an arrogance here among the men, a sense that women

are beholden to their libidos.

Typical of the patriarchal Middle

East (and again, the rest of the world), it can be seen in

the way the men of Beirut hoot and holler as the women walk

by. If

not hooting or hollering out of joy, there are the men who

hiss at the women whom they deem to be dressed too scandalously,

although

beneath the hissing there seems to be the same adolescent giddiness

among these men.

In the Muslim centres of the country, including

the camp, the attitudes towards the intermixing of men and women

are more

stringent, with exceptions. For instance, I discovered that

men in the camps

also engage in purchasing sex , albeit far more quietly and

less frequently. In the camp, dating -- openly dating -- is

strictly forbidden.

Indeed, any activities that include men and women being alone together

are unacceptable--typical of any Muslim country, more or less.

If

a girl and a guy are found to be alone together, they (although

the guy is spared the worst) become the source of a raucous

array of rumours that spread like brushfire in the camps. Eventually,

these rumours reach their families and the real fun starts.

These

stories are not wholly unfamiliar to the Western viewer, but

in Lebanon, the Lebanon of Shia, Sunni, Christian, Druze, and

any of the other 31 flavours that make up this ethnic menu,

these

modes of thought are that much more complicated and contradictory.

For instance, there are the odd contradictions that

bring a smile to my face. In Haret Hreik, a Hezbollah-controlled

area, there are numerous beauty stores and clothing stores that

sell the

latest

in styles from Europe. Women, in the latest styles, make the

main street cause me think I am walking through the streets

of Paris or Milan.

Tight clothes, elaborate makeup, and expensive handbags

contrast with the women who ride with the Turban-clad mullahs that

one

occasionally sees; these are the wives who are covered from

head to toe in a black chador. Yet the two seem to mix well--as

if

this utterly ridiculous mix of Western chic and Islamic religiosity

were meant to meet here in the streets of Beirut.

The

men in the country also speak to this contradiction. While

putting on uber-macho persona of chest hair and greased locks,

they poke fun at each other by evoking the term fag or gay.

There are the men who ride their Japanese motorcycles and rev

their

engines while twisting through the traffic, deafening both

drivers and passengers. Often, they do this in pacts, thereby

multiplying the sound levels.

But there are oddities among this culture of

machismo.

For instance,

men hold hands and link arms. (I found this hard to adjust

to). Even the motorcyclists would have a man sitting on the

back,

clutching tightly to his hips and chest. There is a closeness--a

sensuality--among these men that conflicts with the homophobia

they espouse.

Of course,

the divisions along religious and cultural lines also manifest

themselves between men and women. A close friend of mine here

told me about his previous girlfriend. Being a Sunni, he would

often find himself at odds with her Shia family. Eventually, this

drove a wedge between them and ended their relationship. One

would

be hard-pressed to find Christian-Muslim couples in Lebanon,

even today.

Another story I heard that spoke so well of the

contradictions of life in Lebanon was that of an old man who used

to live

nearby Samer's house in the camp. Apparently, during Ramadan,

the holiest

month in the Islamic calendar, he would make a Jalaab, an energizing

drink that would rejuvenate the exhausted Muslim who was fasting.

A famous drink that Muslims around the world have, it provides

valuable

nutrients to both replenish and serve as fuel

for

the next day of fasting.

But, during the other eleven months

of the

year, he would make Arak, the national and 45 % alcoholic

drink of Lebanon. A typical expectation of the absolute poverty

here

, he would use the same barrels. Everyone

knew about it; and it was acceptable.

Between the sexually

charged and the religiously oriented, Lebanon's true fractured

nature

emerges. (Fractured, although a vivid term, is misleading

for it implies that Lebanon was once united.) One realizes

how mendacious a country Lebanon is.

A justification:

Lebanon was pieced together by the Western powers who were

dividing up the Ottoman empire. The borders of modern Lebanon,

even the

name, is a direct result of the French colonial policy. They

created a country from a collection of nations, of which they

hardly knew anything, and pieced it together to serve their

colonialist pursuits. Much of the Arab world is like this,

with Iraq being

another example, although not to the degree of Lebanon.

The conflicts

in various African countries can also be attributed to these

false borders; borders that force peoples with varying religious

and cultural background to live together in the same countries

but separate worlds. It is here that the seeds of civil conflict,

and the entire turbulent history of the middle east and the Third World (although I

don't like that term), were sown, by the colonialist powers

who felt

that indigenous peoples of the world were not "civilized" enough

to run their own lives and control their own destinies. And just like that, it was done

I have been having a hard time filming my documentary here.

While the people have been very supportive and want to tell

their stories,

I often find myself having a hard time filming. I emerge from

an interview feeling dirty; as if I have taken their lives and

placed them in my bag and walked away with them.

There is truth

to the statement that people are being used during the process.

They invite me to their homes and give me endless coffee, tea,

sweets.

I ask questions in my lousy and awkward Arabic, and when they

ask me to repeat the question--in English--I give up. They tell

of me of their exit from Palestine--how they were forced out

of their homes, how they took whatever they could hold, how this

brother or that cousin was killed.

"My uncle--he was only an infant--they wrapped

him up and took him on their shoulders. When they sat to rest

a few hours later,

they realized that he had fallen somewhere on the road. They

sent his brother to find him, but he never returned." This

discourse of loss--be it land, lives, jobs, freedom--is something

that colours every aspect of life for the refugees.

I hear stories of poverty and despair. Women

prostituting their daughters. Educated men stealing to feed

their families. Young

children leaving school to sell Chiclets and napkins on the side

of the road. When I hear these I always think of how lucky I

am, with my wealth and social mobility. I sit in the lap of luxury

and I decide to drop on these people to gawk and stare.

I arrogantly think that

by writing and filming about their conditions will somehow magically

solve their predicament. Activists come and go, making themselves

feel better and thinking "Well, I did my bit." Then

with our passport we leave and move on to the next tragedy. The

next chic cause that sings to us through the evening news.

Only our planet could produce

a country like Lebanon. There are the memories that I will never

forget: from the beautiful mountains of the Koura

to the luscious waters of the Mediterranean; from the smell of

sewage in Bourj camp to the smell of mass graves in Chatila.

The music of the Mosque in Tripoli to the sound of tankers in

Sidon. The luxury and wealth of Hamra to desolate poverty of

Sabra. From where we can jump into Sea forty feet, to the

roofs of Bourj where houses reach for the sky

and sit only centimetres away from each other.

So here

I sit four and a half weeks and fifteen thousand words later,

and further away from a just answer to the question of Palestine

than ever before. The books and the articles I've read and the

films I've seen never did and never will prepare me for the trenches

of this war--with Bourj being one of them.

A dissolution has

set upon me, with notions of peace and coexistence hanging to

dear life in the parts of my brain that haven't been coloured

by my emotions. Hatred, the hatred that I have as yet been able

to avoid, begins to flower inside a person who sees this place.

The repression of a visceral response to the images of death,

cruelty, and poverty is becoming an exercise in futility.

Before

I came to Bourj, I always tried not to yell at the newscast,

but I let loose on CNN International while Samer giggles at me.

He is used to the miscarriages of truth about his situation.

On a particularly hot and slow afternoon, Samer

and I watched an episode of Full House. I thought

of the world that I was in and the world of the Tanner family.

The real severity

of the

situation these Palestinians are set in while watching the show;

there are no easy solutions to their problem. There is no cathartic

epiphany that comes from all the players involved--where the

piano begins to play and all is made right.

There is no singular

moment where both the "problem" and "solution" become

clear. No point where people realize when the first small crack

in the shell of time occurred. Social justice and matters of

human rights are not simple in a fair world, let alone this place

we occupy.

Y'allah Bye. >>> Part

1

>>> Part

2

>>> Part

3

>>> Part

4

>>> Part

5

>>> Part

6

>>> Part

7

* Send

this page to your friends

|