Portrait of a

city Portrait of a

city

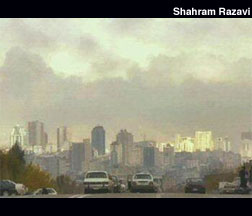

Yes, even in Tehran, even in this crazy, congested,

polluted city, beauty abounds

Sara Valafar

June 9, 2005

iranian.com

Today, July 10, 2004, I walked around Tehran with my ankles showing,

blissfully unaware of the danger posed by the green-and-white security

cars, and uncomfortable only for feeling myself, as an American

tourist, on the fringe of society. Tehran is a city of contrasts;

modern sits

side by side with tradition and even destruction. On the way to

Shahrvand (think upscale Wal-Mart), we passed by several gleaming

apartment

complexes, sturdy square boxes lacquered in granite and marble;

but for each one of those exists a gutted, sagging edifice, limned

in

scaffolding, staring through hollowed eyes.

The lot at the end

of my in-laws' street housed a half-finished building for years

and

then, bang, this year we arrive and a brand new research facility

plus several small apartment complexes are standing proudly, as

modern in design as you would see in the most advanced cities,

of the most

advanced nations. Yet the detritus remains, rusted pipes stacked

like fuzzy caterpillars, weary wheelbarrows, a mélange of

broken tiles and bricks, masses of wires, and heaps of rocks and

dirt

that seem to have nowhere else to go.

War-torn Tehran has been recovering for years, at a stand-still as far as progress

and productivity are concerned. But today we passed a construction site where

cement mixers actually churned and men ranged all along the scaffolding with

trowels in hand like insects along the exoskeleton protecting some larger beast.

In the once elite northwest corner of Tehran, where my in-laws reside, you can

find houses as large as palaces, corniced and columned like wedding cakes, guarded

by the most delicate of iron scrollwork across the windows and doors. Across

the street sits a lone newspaper stand fashioned from an iron hut, flanked by

yet more rubble and the droppings of yesterday's

passersby.

So went the drive to Shahrvand, a study in contrasts, faded rugs hanging from

the balconies of anonymous stucco buildings, tradition and modernity ranged side

by side. Tehran was once a lovely cosmopolitan city, arm in arm with Europe as

far as culture and fashion trends were concerned, and much as one views ruins

in which the bare structure remains, it is possible to squint and imagine Tehran

as it was: a few cars humming quietly on wide, sweeping streets shaded by the

shaggy maple-like leaves of the elephantine chenar trees, streets giving way

to dirt alleys and sun-baked brick walls enclosing orchards grown in the mountains'

folds.

The streets of Tehran are now a cacophony of cars, cars honking at pedestrians

who flit through traffic like the frog in that early computer game, trying not

to get squashed (crosswalks are nonexistent), cars honking at cars darting insanely

into the stream of

oncoming traffic, cars honking at policemen ("pimps," my father-in-law

calls them) who attempt to direct the traffic, superseding the traffic lights.

Once in a taxi cab, the driver suddenly swerved onto the sidewalk to clear traffic.

He turned back and grinned at the

expression of horror on my face. "You don't do this in America, do

you?" he asked.

The staggering opulence to certain aspects of Iranian life always amuses me.

Amid the typical squalor of poor city living, granite and marble abound. The

mountains surrounding Tehran are full of natural rock and semiprecious stones

and, as a result, granite and marble cover everything from storefronts to sidewalks.

The contents of dented metal trash cans overflow across black lacquered walkways;

marble staircases lead to gloomy office buildings; chandelier and rug shops displaying

spectacular examples of crystal and the finest of hand woven silk tapestries

are framed by shining granite tiles -- these in turn are under the rubric

of garish neon signs, pulsing on an off

as far as the eye can see.

Iran has long resisted typical Western culture: fast food restaurants, chains

of department stores, the fast and easy life style. But now fast food restaurants

were opening like a pox onto the city (I saw my first fat Iranians, crowded into

one of the small

shops), and in front of one of the new modern malls (enormous -- seven stories

high) a man stood, thrusting flyers into people's hands advertising Gap, Banana

Republic, and Old Navy. While I often moan about the difficulty of doing even

small things in this enormous city (a trip to the bazaar to buy spices is an

all-day affair), it would be decidedly worse for Tehran to become another Western

rip-off.

Conversely, these signs of Western influence are also signs of the economy picking

up, and Iranians have lived so long in poverty, working two or three jobs to

make ends meet, that one cannot help feeling hopeful about the surge. (Though

I sometimes wonder if the extra money the city has to spend will be detrimental

in the long run.

During one trip to the bazaar, we passed by workers resurfacing an old brick

wall in a random pattern of broken colored stone; the effect was very modern

and still appealing, but my heart sank as I saw that lovely old brick covered

up forever. Half the wall had been resurfaced already -- in the other half the

brick stood out like the living insides beneath flesh, pulsing for one last beat

before being overlaid. It was as good as gone, save to those who knew of its

existence, who could feel, perhaps, in passing by, its continuing pulse beneath

that surface of cold stone.)

The drive home from Shahrvand revealed mounds of dirt topped with a lone tire,

children playing soccer in a run-down lot, miles of high-wattage neon lights

lining the wide streets of the once central part of Tehran. We stopped by one

of the oldest city parks, Park-e Jamshid, famous for its double embankment of

steps lined with the stone heads of famous poets, then crossed back over the

main street (a delicate operation, as graceful as a dance, the quick step in

front of streaming cars, the pause and step again as you negotiate from lane

to lane, praying to Allah not to get squashed as cars pass within an inch of

your body). The staggering opulence to certain aspects of Iranian life always amuses me.

Amid the typical squalor of poor city living, granite and marble abound. The

mountains surrounding Tehran are full of natural rock and semiprecious stones

and, as a result, granite and marble cover everything from storefronts to sidewalks.

The contents of dented metal trash cans overflow across black lacquered walkways;

marble staircases lead to gloomy office buildings; chandelier and rug shops displaying

spectacular examples of crystal and the finest of hand woven silk tapestries

are framed by shining granite tiles -- these in turn are under the rubric

of garish neon signs, pulsing on an off

as far as the eye can see.

Iran has long resisted typical Western culture: fast food restaurants, chains

of department stores, the fast and easy life style. But now fast food restaurants

were opening like a pox onto the city (I saw my first fat Iranians, crowded into

one of the small

shops), and in front of one of the new modern malls (enormous -- seven stories

high) a man stood, thrusting flyers into people's hands advertising Gap, Banana

Republic, and Old Navy. While I often moan about the difficulty of doing even

small things in this enormous city (a trip to the bazaar to buy spices is an

all-day affair), it would be decidedly worse for Tehran to become another Western

rip-off.

Conversely, these signs of Western influence are also signs of the economy picking

up, and Iranians have lived so long in poverty, working two or three jobs to

make ends meet, that one cannot help feeling hopeful about the surge. (Though

I sometimes wonder if the extra money the city has to spend will be detrimental

in the long run.

During one trip to the bazaar, we passed by workers resurfacing an old brick

wall in a random pattern of broken colored stone; the effect was very modern

and still appealing, but my heart sank as I saw that lovely old brick covered

up forever. Half the wall had been resurfaced already -- in the other half the

brick stood out like the living insides beneath flesh, pulsing for one last beat

before being overlaid. It was as good as gone, save to those who knew of its

existence, who could feel, perhaps, in passing by, its continuing pulse beneath

that surface of cold stone.)

The drive home from Shahrvand revealed mounds of dirt topped with a lone tire,

children playing soccer in a run-down lot, miles of high-wattage neon lights

lining the wide streets of the once central part of Tehran. We stopped by one

of the oldest city parks, Park-e Jamshid, famous for its double embankment of

steps lined with the stone heads of famous poets, then crossed back over the

main street (a delicate operation, as graceful as a dance, the quick step in

front of streaming cars, the pause and step again as you negotiate from lane

to lane, praying to Allah not to get squashed as cars pass within an inch of

your body).

Iranians love nature and anywhere there is a patch of green is an opportunity

for a blanket and a samovar; you can find families sprawled out into the latest

hours of the night enjoying conversation and cups of tea, sprawling everywhere

from parks to the grass strips lining highways. The parks of Tehran are incredibly

grand, large sweeps of land blooming with flowers or bursting with trees and

fountains. The paths are numerous and winding, surrounded by large swaths of

green; it is amazing how much space is devoted to these natural preserves in

a city choked with buildings and cars and people,

where land value is at a premium.

Yes, even in Tehran, even in this crazy, congested, polluted city, beauty abounds.

And from my view on the park bench, at the end of this long July day, I realize

that the best word to describe this city is majestic; majestic are the parks

where the trees aspire to the sky and the sky aspires to the highest peaks of

the mighty Alborz mountain range; majestic are the streets, crazy, turbulent,

honking, neon-lit, chenar-swept streets; majestic even are the blocks of apartments

and office buildings, majestic by sheer volume, which spread like a cancer in

all directions, devouring orchards and fields and walls; and majestic are the

people here forging through the chaos, whirling like dervishes in this crazy

dance that is Iranian life. Iranians love nature and anywhere there is a patch of green is an opportunity

for a blanket and a samovar; you can find families sprawled out into the latest

hours of the night enjoying conversation and cups of tea, sprawling everywhere

from parks to the grass strips lining highways. The parks of Tehran are incredibly

grand, large sweeps of land blooming with flowers or bursting with trees and

fountains. The paths are numerous and winding, surrounded by large swaths of

green; it is amazing how much space is devoted to these natural preserves in

a city choked with buildings and cars and people,

where land value is at a premium.

Yes, even in Tehran, even in this crazy, congested, polluted city, beauty abounds.

And from my view on the park bench, at the end of this long July day, I realize

that the best word to describe this city is majestic; majestic are the parks

where the trees aspire to the sky and the sky aspires to the highest peaks of

the mighty Alborz mountain range; majestic are the streets, crazy, turbulent,

honking, neon-lit, chenar-swept streets; majestic even are the blocks of apartments

and office buildings, majestic by sheer volume, which spread like a cancer in

all directions, devouring orchards and fields and walls; and majestic are the

people here forging through the chaos, whirling like dervishes in this crazy

dance that is Iranian life.

|