Obrigado

Brazil Obrigado

Brazil

Brazilians I saw to be a highly sociable and charming

people among whom hugging, kissing, and passionately engaging

interactions are as normal as breathing air

Ali Akbar

Mahdi

August 17, 2005

iranian.com

I just came back from a short trip to Brazil. Prior

to a conference, I spent a few days in a couple

of cities visiting communities, museums,

markets, and parks. I tried to check my book-learned knowledge

of this country and its people with realities on the ground. I

had many discussions with people about a country which I had known

from the literature as home to an “ethnic democracy.” Brazil

is a country approximately as large as the United States with just

as diverse and beautiful landscape and people.

As a society composed of people of diverse colors, backgrounds,

cultures, and religions, diversity seems natural to these people.

As a “foreigner,” I never felt I was “watched” or

appeared out of place. Smiles are abundant, people interact with

calm and ease, and the society has a very peaceful appearance.

If I had not read about subtle discriminatory attitudes based

on color and history in this former Portuguese colony, I would

not

have even noticed the different standings of people relative

to their ethnic background and skin color. There are certainly

discriminatory

practices related to color and heritage but they are subtle and

often only visible at the categorical level and not within individual

interaction. To see it more clearly, you have to look at statistics

about jobs, opportunities, geography, ethnicity, and pigmentation.

Politically speaking, people speak their mind openly and no

one is scared of losing a job or risking jail by expressing views,

quite a contrast to what you find in the Middle East and parts

of Africa. People openly talked about the recent corruption

that

led to the resignation of President’s chief of staff Jose

Dirceu -- one of the most powerful figures in Brazil’s

government. Politically speaking, people speak their mind openly and no

one is scared of losing a job or risking jail by expressing views,

quite a contrast to what you find in the Middle East and parts

of Africa. People openly talked about the recent corruption

that

led to the resignation of President’s chief of staff Jose

Dirceu -- one of the most powerful figures in Brazil’s

government.

Socially, I was stimulated by the spirit of a people

who appear happy most of the time, even in the worst of conditions.

I find the Brazilians I saw to be a highly sociable and charming

people among whom hugging, kissing, and passionately engaging

interactions are as normal as breathing air. Having grown up

in a Middle Eastern

culture with strong inhibitions for public expression of erotic

feelings, I was impressed by people of Olinda and Recife who

show

affection towards their partners openly and generously without

cultural reservations.

Although Brazil is very diverse, including

people descended from Africans, Europeans, Asians, and natives

from all over the Western hemisphere, it remains predominantly

isolated from the rest of Latin America. Portuguese is the

dominant language and in non-tourist areas you do not find, at

least in

my brief experience, many people speaking English. I was told

that

even the Spanish language, which is dominant in the region,

is sparsely understood here. As one moves away from tourist cities,

one is hard pressed to find someone communicating in non-Portuguese

languages, even in airports!

Coming from America, a country in which two-thirds of the population

is considered overweight, one is surprised by how fit most people

look in Brazil. Following the motto of “looking good is halfway

to feeling good,” urban Brazilians I saw seem to be highly

body conscious, especially women. No wonder many workout programs

in the West are either originated from or named after Brazil. I

found most Brazilian women I spoke with to be weight conscious,

highly careful in their diet, and very physically active. Maybe

this explains why Brazil has the third highest rate of plastic

surgery procedures in the world (behind the US and Mexico).

What is very visible in Brazil, and very disturbing, is the wide

gap between the poor

and rich. Sao Paulo, Brazil’s commercial

magnate, with a population of some 20 million, is an economically

polarized city. Other cities are not exempted from this ugly reality.

Many Brazilians speak of Rio de Janeiro with a sense of its loss

to poverty, crime, drug, prostitution, etc. Streets in central

cities and tourists areas are full of poor people selling any manner

of objects to make a living, sleeping

on the sidewalk, or begging

for food and money. What is very visible in Brazil, and very disturbing, is the wide

gap between the poor

and rich. Sao Paulo, Brazil’s commercial

magnate, with a population of some 20 million, is an economically

polarized city. Other cities are not exempted from this ugly reality.

Many Brazilians speak of Rio de Janeiro with a sense of its loss

to poverty, crime, drug, prostitution, etc. Streets in central

cities and tourists areas are full of poor people selling any manner

of objects to make a living, sleeping

on the sidewalk, or begging

for food and money.

As a casual observer, you cannot but be surprised

by the number of lottery

stores selling dreams to so many customers

on almost every street. In big cities like Sao Paulo and Rio de

Janeiro, city highways and streets are crowded by people who take

advantage of traffic lights to sell something to drivers in order

to make a living. The number of homeless has been increasing by

the day, especially in major industrial cities.

Thanks to neo-liberal

policies imposed by international financial institutions, the Brazilian

economy has created one of the most unequal societies, not only

in Latin America, but also in the world. Today 46.7% of Brazil’s

national income goes to richest 10% of the population, while the

poorest 10% of people receive only 0.5% of this income! And yet

Brazil has continued to remain on the list of top five indebted

nations in the world! As happy as Brazilians look on the street,

their share of public services (education, health, and security)

is the lowest in Latin America.

This increasing economic inequality has contributed to a rise

in unemployment, crime, human trafficking, child labor, and the

like. Increasing crime has created a very insecure environment

in a society known for its kind and peaceful people. Today, the

security industry is the fastest growing business in major cities,

and drug lords are becoming the major players in cities like Rio

de Janeiro.

Most houses in wealthy neighborhoods have a security

booth with a posted guard watching behind tinted glasses. Crime

has also affected safety concerns for businesses and tourism

in urban areas. It is rare to find nice houses without a guard,

security

system, or walls with sharp glass or electric

wire on top. Most houses in wealthy neighborhoods have a security

booth with a posted guard watching behind tinted glasses. Crime

has also affected safety concerns for businesses and tourism

in urban areas. It is rare to find nice houses without a guard,

security

system, or walls with sharp glass or electric

wire on top.

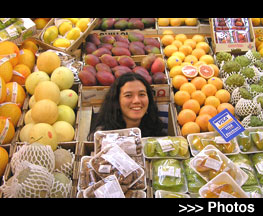

The

pictures you see here are selected from a large pool to demonstrate

some of my impressions. They represent scenes, events, and faces

from Sao Paulo, Salvador, Recife, and Olinda. I would like to thank

those Brazilians who shared their time with me and helped me to

better understand their society and culture: “Obrigado” (thank

you).

About

Ali Akbar Mahdi is Professor at the Department of Sociology

and Anthropology in Ohio Wesleyan University.

|