به زبان فارسی

PICTORY

LATEST MUSIC

SEARCH

Why I feel for Roxana

by true story

22-Apr-2009

Watching what has happened to Roxanna Saberi convinced me that I have to share my story, even if it endangers me further. Some of the names, dates and places in this brief article may be blurred, but the story itself is true. It’s about how I was detained by the Iranian authorities, survived five days in Evin and then managed to buy my freedom back – at least temporarily.

I am not a frequent visitor to Iran. Like most Iranian-Americans, I have few other reasons to visit than to see my ailing parents and the remnants of a once large family that is still left in Iran. In the 1990s, I only made two visits. Both were brief, and both were relatively uncomplicated. After my father’s heart attack in 2002, however, I have visited the “homeland” three times. Though my parents are still alive and cannot travel, I will visit Iran no more.

Here’s why.

Early one spring morning, two civilian clothed men knocked on my mother’s apartment in Yousefabad, Tehran. The time was probably no later than 7am, though my memory may fail me on this detail. They said they wanted to have a word with me. They didn’t identify themselves clearly, but it was obvious they were with the authorities. We had just woken up and were preparing ourselves for a several hour drive to a village outside of Tehran.

We invited them in and offered them tea and fruit. They asked me a few questions about my work in the United States. They also asked me why my wife didn’t travel to me to Iran. I explained our work situation. They responded by asking if I trusted my wife being alone in the US. I was both insulted and baffled by the question. My mother noticed my irritation and jumped into the conversation with a lame joke. The two men – who looked as if they were brothers – shifted gears and asked me instead of what I thought of Iran. They asked meaningless questions, I gave them meaningless answers. The conversation lasted no more than 15 minutes. They thanked us for our time and left.

We were obviously disturbed by the visit and cancelled our trip out of the city. For the next few days, there was an anxiety in my stomach that I simply couldn’t shake. After about a week, things started to turn back to normal. There were no signs of the two men, and we began thinking that the entire episode may have been a case of mistaken identity.

But then, only a few days before was scheduled to return to the States, we received a phone call around midnight. I picked up the phone and a voice said he wanted to speak to me. There was no hello, no “how are you doing.” He identified himself as a representative of “ettela’at” and that I had to appear at the gates of the ministry tomorrow morning at 8am. He gave me the address and told me not to be late. I protested and said that I have plans and could make it tomorrow. He paused for about 30 seconds. If it wasn’t for his breathing, I would have thought that the line had been cut. In a very angry and stern voice, he told me that this was not a request. This was an order by the nation’s security personnel. His tone made it very clear that I was in trouble and that arguing would not help my case. But I still managed to ask him why I was “ordered.” We ask the questions here, not you, he responded. Then he hung up.

I was terrified, but I didn’t tell my parents about the conversation, fearing that my father’s heart wouldn’t be able to handle the anxiety and fear. I was up all night, thinking about my wife and two kids.

The next day, I left early and arrived at the address I had been provided. It was not the ministry, but a private resident. I stood by the gates and exactly at 800am a white car stopped next to me. A man jumped out of the back seat, opened the back door and ordered me to take a seat. I complied, he sat down next to me and then we drove off. Four people were in the car besides me. The driver, a person in the front seat whose face I never really saw, and two men to my left and right in the back row. No one said a word. After 10 minutes of driving, I asked quietly where we were going. No answer. After another 10 minutes or so, I tried to stretch out my left arm to get a glimpse of my watch, but the man to my right quickly grabbed me arm and stopped me. He didn’t say a word, but he kept holding my arm for the duration of the drive.

After another hour or so, we began approaching my parent’s apartment in Yousefabad. The driver stopped at the corner, the man to my right jumped out, dragging me out with his left arm, and then jumped back into the car. Without saying a word, and without giving me a chance to ask a question or take a peek at their faces, the car drove away. I had parked my car near the address they had provided, so bringing me back home was most unhelpful.

After an initial period of anger and fear, I started suspecting that their aim was solely to play games with my mind and that my best defense was not to permit them to “get to me.”

But I was proven wrong. That same evening, they called again. This time, they were rude and aggressive, accusing me of wasting their time and not cooperating with them. He ordered me to appear at the same address the next day at 900am. Bring your Iranian and American passports and “shenasname” in a yellow envelope, he ordered me.

I felt extremely uneasy about this, but complied with his demand. This time, I left my parent’s car at home. At the gate, a person appeared quickly, took the envelope (it was white, we didn’t have any yellow envelopes) and disappeared. I stayed around, not knowing what to do. They had my passport and my Iranian ID, so I didn’t want to leave, particularly since I was supposed to fly back to the US only days later. But no one showed up, and after 2 hours of waiting, returned home.

By now, I had to explain the situation to my parents since I suspected that I wouldn’t be able to make my flight back to DC. My frustration was overwhelming, I had no way of contacting these people, and they had all my travel documents. I was stuck, and did not even know who to contact to demand my rights.

I called my wife to explain the situation and prepare her that I might not make it back to the States according to our original plans. I also called and informed my employer.

That night, I sat with the phone in my lap, waiting for a call. But no one called. In fact, it took an entire week before they called again. By that time, I had not only missed my flight, I had also lost my ticket (that’s another story though).

Now the caller was suddenly very polite. He asked me why I hadn’t been in touch and that they had waited for me. I blew up in anger screaming at him that they are toying with people’s lives. He listened calmly and only responded after my outburst that I should come in tomorrow so that the situation could be resolved.

When I showed up the day after the gate was open. A voice on the intercom ordered me to enter and go to room 312.

The door to room 312 was open. Inside there was a desk, and a metal chair for visitors. No one was in the room. There were no pictures on the walls, and there was no window or any lights. All the light in the room came from the hallway. After about fifteen minutes, the two men that had knocked on my parent’s home showed up. They greeted me with big smiles, asked me how I was doing, and expressed regret for the entire situation. Of course, it was all my fault though. They did not know that I was planning to return to the US so soon, because I had never told them that, they claimed. Also, I had not followed instructions – why did I put the passports in w white envelope when they had asked for a yellow one? As a result, I had only myself to blame for putting THEM in the situation of having to do this to me.

They assured me though that the entire situation was a mistake, and that it would be resolved the very same day and that I would be free to leave with my passports. I just needed to answer a few more questions.

They took me to the unnumbered room to the left of 312. This room was a bit bigger, and it had a few more chairs. And a ceiling lamp, but no window. And for some reason, it was very warm in the room.

Three chairs were facing a desk in the middle of the room. They put me in the middle chair, while seating themselves to the right and left of me. They told me that one of their superiors needed to ask me a few questions, after which I could leave. Surprisingly, their superior entered the room almost immediately after we sat down (by now I had grown accustomed to waiting). He was tall, had no beard, didn’t look like the typical regime-supporter and in his hand, he had a white envelope.

He began asking me questions about my childhood, why I left Iran, why I settled in the US, what kind of car I drove, where my first house in the US was, what I thought of my American co-workers, what my parents thought of Iranian healthcare, and so forth. It was ridiculous.

After almost an hour of this senseless chit chat, I gathered courage and asked him why on earth this information was of any interest to them. Within a second, the mood in the room turned 180 degrees. As you wish, he responded, with a deceptive voice, we can ask you other questions. He opened the envelope and took out a few sheets of paper and a pen.

Here, write everything you know about Goli Ameri and the Republican Party on these sheets of paper, he ordered. Who, I responded, in bafflement? The Republican party!, one of the men sitting next to me screamed in my ear. We know what you are up to, the other man yelled.

I tried to defend myself and say I have no particular knowledge of the party or Goli Ameri. LIAR, they shouted back, and put a new sheet of paper on the desk in front of me. It was a print out of my financial contributions to various lawmakers from Huffington Post, none figuring more than $300. This is nothing, I said. I have given money to the democrats too, so why don’t you ask about that?, I said in my defense. “Don’t worry, you will write about that too,” they shot back.

To make a long story short, in the next few hours, they forced me to write everything I knew about a dozen US lawmakers, of whom I had only met one or two. Yet, I had to write – in my less than perfect Farsi – everything about them without any of my interrogators ever explaining what they were looking for or what I should focus on. They also wanted me to write everything I knew about PAAIA – an organization I had not supported financially. But someway somehow they knew I had attended a presentation by PAAIA in Houston in late November 2007.

To no one’s surprise, they never returned my passports that day. Instead, I spent the next three months stuck in Iran, paying visits to the intelligence officers every three days or so, writing pages after pages about a variety of seemingly unconnected political issues in the US. While their tactic probably was to confuse me and never reveal what they were looking for, I believe I detected three elements that they centered on.

First, they wanted to know about Republican outreach to the Iranian-American community and key leaders among Iranian-Americans that the Bush republicans relied on. They asked more about Goli Ameri and my financial support to her campaign than they did about any of the lawmakers that I had given less modest donations to. Secondly, they asked about my involvement in Iranian-American organizations, which is truly non-existent. I don’t support any Iranian-American organizations, and besides my attendance of a PAAIA meeting, I do not attend Iranian-American gatherings, not even Nowrouz events. Finally, they wanted to know about how Republican operators in the community, with the potential help of Iranian-American organizations, were recruiting people to support secret regime-change efforts conducted by the US government itself.

Since I knew so little about these things, I essentially had to make up stuff to satisfy them. I really understood why torture is such a useless technique – when under pressure, people say whatever their interrogators want to hear. I knew nothing about the issues they asked about, but someway somehow I subconsciously provided answers that I felt would satisfy their curiosity.

I don’t know why they targeted me in the first place. I am sure there are plenty of other Iranian-Americans, far more politically plugged in than I, that they could target. Perhaps the reason was as simple as them doing searches on the internet, finding my name on both the list of Goli Ameri’s donors in 2004 and the list of donors to the GOP. Realizing that I was in the country, they took the opportunity to snatch me. Or perhaps it’s much more complicated than that.

I don’t know the answer to these questions, and I fear I will never find out. What I know is that they ruined my life. I lost my job, missed my daughter’s graduation and had to provide the deeds of my uncles house (my parents’ house wasn’t expensive enough) to get myself out of Evin (after two months of questioning, I tried the tactic of refusing to cooperate with them, which turned out to be a big mistake – they escalated by placing me in Evin for a few days.)

Though they let me go after three months, they still have a “parvandeh” on me and my case is not unresolved. If I do anything that angers them, they may retaliate by evicting my uncle from his house. So for more than a year, I have been silent. But after hearing about Roxana’s case today, I felt I had to come forward and at least share my story with other Iranian-Americans. Perhaps it can help people avoiding my faith. And perhaps it will help people realize that Roxana is most likely innocent.

This government treats innocent people worse than those that are guilty, I have come to learn.

RECENT COMMENTS

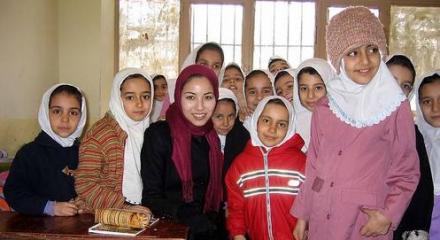

IRANIANS OF THE DAY

| Person | About | Day |

|---|---|---|

| نسرین ستوده: زندانی روز | Dec 04 | |

| Saeed Malekpour: Prisoner of the day | Lawyer says death sentence suspended | Dec 03 |

| Majid Tavakoli: Prisoner of the day | Iterview with mother | Dec 02 |

| احسان نراقی: جامعه شناس و نویسنده ۱۳۰۵-۱۳۹۱ | Dec 02 | |

| Nasrin Sotoudeh: Prisoner of the day | 46 days on hunger strike | Dec 01 |

| Nasrin Sotoudeh: Graffiti | In Barcelona | Nov 30 |

| گوهر عشقی: مادر ستار بهشتی | Nov 30 | |

| Abdollah Momeni: Prisoner of the day | Activist denied leave and family visits for 1.5 years | Nov 30 |

| محمد کلالی: یکی از حمله کنندگان به سفارت ایران در برلین | Nov 29 | |

| Habibollah Golparipour: Prisoner of the day | Kurdish Activist on Death Row | Nov 28 |

Dear "true story"

by MiNeum71 on Wed Apr 22, 2009 12:18 PM PDTThis sounds like a political version of North by Northwest. I´m sorry for you, I hope your (Iranian) story turns to good account.