به زبان فارسی

PICTORY

LATEST MUSIC

SEARCH

Dirty business

by Manoucher Avaznia

09-Nov-2007

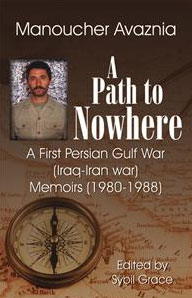

From "A Path To Nowhere" by Manoucher Avaznia (Infinity Publishing). The triangular relationship between dictatorship, arms, and oil has begotten a mass murder called war that has plagued the people in the region around the Persian Gulf. See another excerpt.

On January 4, 1987 I was spending my third night at the front line. I had already received a Klashinkov rifle with a magazine that could hold thirty cartridges and a few blankets to sleep in as Neekvarz had promised. That night it was cold and foggy. A storm was blowing from northwest raising sand and dust; making the air dark. Apprehensive about my sentries, I had visited all of them twice earlier at night either in Karamee's company or on my own. All of them were awake and vigilant; everything seemed normal except the storm that was lashing across the plain and the hill.

On my last return to the bunker my head struck the ceiling log and badly hurt. As I sat down Haghee phoned:

"How are you Avaznia?" he asked.

"I am very well, thank you Sir;" I answered.

"I just wanted to know how the front line tasted?" he asked.

"As normal as life itself Sir," I returned.

I reported that everything seemed normal; he warned that in stormy weather could lay more dangers. The enemy could have taken advantage of our limited visibility and hearing to sneak quite close to our position before we noticed their presence.

"Volleys of hot lead will be awaiting their madness," I responded boastfully not knowing whether it stemmed from the pain in my head or from my own fear and he laughed, "In any case, we are all ready."

In spite of what I had expressed, I was anxious. An unease was assailing my within without me knowing what was stored in the heart of the night. I reviewed my previous few days and thought about Haghee's warning; but I could not find anything specific to worry about. I was in the front line and everything was as I had expected. Considering my family's anxiety and the fact that I had told them I would be kept in the garrison for sometime before being dispatched to the front line could not be the cause either. Quitting smoking since my arrival to the front line had not made me anxious either; though it had made me utterly nervous. Failing to find a specific reason, I convinced myself to believe that my anxiety was because of all those factors. Putting my rifle beneath my head, I wrapped myself in my overcoat and slept in my boots with my feet towards the entrance while Abbasspour slept in my place.

At one o'clock in the morning our telephone rang aloud. The operator told Abbasspour a group of soldiers consisting of eight soldiers and an officer from our battalion were scheduled to go on a reconnaissance mission on Iraqi positions at four o'clock of the same morning from my place. I was to order my soldiers not to shoot forward until they returned at dawn.

For the first time I was hearing of such a daring mission happening under my own nose and profoundly revered the nine brave men. To make sure my soldiers would not shoot, I wanted to be meticulously careful the order reached every single soul under my command. Therefore, I sent Abbasspour to call Karamee to see me in person to receive the order directly from me.

Karamee was very late to show up adding to my anxiety. After almost half an hour he entered with a "Salam: hello" at the door.

"Hello and death!" I retorted angrily, "I have been waiting for you for half an hour. You were sleeping on duty."

"I say hello and you return death," he objected aloud, "It's not the proper answer to hello. You don't have war experience and get excited about ordinary things. We see reconnaissance groups every day."

"Anyway," I said, "These people are going on this mission. Make sure your guards do not shoot forward until all of them are back safe. Tomorrow I will find a more active guards chief to replace you."

"Do whatever pleases you," he said discontented and hurt while leaving my bunker with the piece of paper on which I had written the number of the people, the time, and the place of their dispatch.

Lying on the floor, I fell to an uneasy asleep. I did not know how Abbasspour was feeling about living with a nervous man that I was that night. In my nervous speaking I did not have anything less than the shell-shocked officers I had seen until then. Most probably, like most soldiers, Abbasspour thought: "two years of military life must be spent bitter or sweet".

A conversation between Abbasspour and the wireless operator of the reconnaissance group woke me up again. It was around four in the morning. They were talking about adjusting their radio frequencies and channels. As they were still talking I fell asleep again.

At 6:oo a.m. of 15th of the Iranian Month of Day 1365, January 5, 1987 of Christian Calendar, I was awakened for morning exercise. It was still cold and misty, but the storm had stopped. Soldiers were awaiting me around their morning fire. We ran a short distance and returned to the place of exercise and while everyone was still exercising I left for my bunker for breakfast.

Abbasspour was sitting beside his wireless. The breakfast of cheese, bread, and tea was ready. We were chewing the first mouthful of bread and cheese that I heard someone saying: "Hurry up guys".

Shortly after, I heard footsteps running around my bunker. The exercise should have been ended and soldiers must have been running towards their bunkers to take their guns to shoot at the flock of geese that flew northward from marshes of Hoor-al-Hoveizeh every morning. I had no objection to their shooting; rather I believed it would entice them to improve their skills. This did not last long though. In less than a minute Neekvarz called me on our telephone set. His voice was shaking, his words running into one another.

"They report a soldier of the reconnaissance group has been martyred," Neekvarz said, "They need our assistance to evacuate him. Send two soldiers to their assistance. Don't let more than two soldiers go. I am afraid Iraqis will pinpoint them with mortar rounds."

I had not heard any explosion; no one had reported shooting either. What Neekvarz said was rather strange a thing. It meant my soldiers' "hurry up guys" to be a disaster that had just struck. My soldiers were aware of the incident before any commander knew anything about it. They even did not let me know about it.

The news was grave; I was frozen; my mouth dried. I could not swallow contents of my mouth and threw it on the sand in front of the bunker as I was running towards my soldiers who were running to the place of incident between the two front lines. I stopped all of them as Neekvarz had ordered except Karamee and Gorjee who were running ahead of everybody. To train myself to overcome my dread of death, I kept running on the dune towards the victim. After all, being killed by shells and shrapnel was an everyday happening here.

Several hundred meters away, where the dune hills ended and the flat land started, I saw two other soldiers besides Gorjee and Karamee carrying a wounded soldier on a stretcher. Both of his legs had been broken and partially severed by explosion. There were some minor injuries inflicted to his arms and hands. He had put his forearm over his eyes. Bleeding had stopped and he could clearly hear and speak. He knew Karamee; apparently, both of them came from City of Dezful in northern Khuzestan.

"Do you know him?" he asked Karamee, "I am his brother. Tell him you saved me."

Karamee told the wounded man his injuries were not serious in order to keep him in high spirits. I helped with the stretcher for a few paces before I noticed the expanse of the disaster went beyond what had been reported. A soldier had received shrapnel in his genitals unable to take even one step. Another had lost a foot and was still on the ground; a third had shrapnel in his arm. The commander, a third lieutenant in rank, had a wound in his shoulder. The fifth soldier had swooned: witnessing the scene was beyond his ability to bear. We needed more help to carry all the wounded. As long as mist had covered the area we were safe to deploy more help. I could not call out for more assistance lest the Iraqis heard me. So I started running back to mobilize as many soldiers as I could.

On my way I saw Neekvarz with Abbasspour: his wireless on his back, going to the wounded. He was pale, scared, frowned.

"Nobody's dead," I said as I was running, "But all of them are wounded." I was so agitated that I did not know precisely what I was saying.

"Sir;" Neekvarz tried to call my attention, "Be careful with mines! They are scattered all over this area. I almost put foot on one. Put your foot exactly on my footprints. We don't need more casualties."

I heard nothing more of his words and kept running without much care about the mines that I had not seen yet. Before reaching the platoon I saw my soldiers walking in a track that led to the place of the incident. They started to run as soon as I told them about the wounded. In my bunker I telephoned for another ambulance and walked toward the injured: being carried on stretchers and my soldiers' backs and arms. The group radio operator was sitting on the ground unharmed, weeping. To lift his spirits, I tapped him on the shoulder.

"A brave man like you never cries," I said.

He tossed his wireless on his back, I took his gun and we walked toward my platoon.

"I have lost my compass," he said sobbingly.

"It doesn't matter," I interrupted, "You are not injured."

"I am not afraid of injury and death at all," said the young man, "The hurting thing is that I don't understand why we are losing our lives in this useless war."

"Nobody understands that," I said, "Everybody knows that fighting is a dirty business."

"More painful is that they don't care about our lives," he said still crying, "But they will ask me about the compass. We did not have enough metal plates to build a good bunker and so we tried to take a few plates from the Iraqi abandoned bunker when the trapped mine went off."

Minutes later all the wounded were evacuated to the ambulances behind the hill and were driven to the hospital. I was left with my soldiers and a bitter memory. All of us were sad. I wanted to thank my men for the excellent work they had done and called them together.

Sad figures with hung-down mustachios and bloodstained uniforms gathered with eyes tied to the ground awaiting me to break the dull and dead silence.

"Guys!" I said with a lump in my throat, "I thank you for the excellent job you did for your wounded friends. I am proud of you. You should know that in this butcher's house you are the first ones and the last ones to help one another. Karamee; I am sorry about last night. I had smelled blood without knowing it was coming in this way!"

I could not continue and asked if they had anything to add. Nobody said anything. Lest an Iraqi shell landed among us, I told them to go to their bunkers.

My soldiers dispersed; I began smoking my first cigarette after five days; and the disaster that befell us in this way overshadowed Hassan's stories and plight. He could walk and live his ordinary life; he was able to attend university without wheelchair and crouches. The man who had lost both feet would not be able to do most of what Hassan could do. The one who had received shrapnel in his genital, I heard was one of Taghee's captors, lost his life. Is there a correct way to compare and measure people's plight, although some overshadow others? Where is the scale?

At night I asked Abbasspour about the mine the soldier had mentioned to me. In a calm and low-pitched tone he answered that the mine was called Valmeri and he guessed it was made in the Soviet Union.

"It has five feelers and a knot for trapping," he added, "If any of the feelers or the trap line is touched or pulled, the mine jumps to the air up to the waist of the person and detonates with thousands of shrapnel."

I told him the wireless operator had mentioned metal plates.

"Right now we have two soldiers from our own platoon in the hospital for the same reason," Abbasspour answered, "When we came here we were crazy. There was not much supervision and soldiers used to freely go to the area between the two front lines to harass Iraqis in different ways. Even some commanders took part in the adventures. Lieutenant Assadi, who has lost a brother to the war, used to take a soldier and go all the way to the Iraqi line shoot at them and come back. Valee who is a crazy man in the neighboring platoon and two of his brothers have been executed for drug trafficking once went all the way to the Iraqi minefield by himself and brought back an anti-tank mine. No one could take the damned mine away from him. He was threatening he would drop it with the pedal to the ground to kill every one who tried to take it away. Finally, the commander of the battalion charmed him with nice words and promised a-one-week-leave and took the mine away from him.

Any way, the result was that the soldiers discovered Iraqis had abandoned some well-built bunkers between the two front lines. We needed their materials as we needed to build bunkers for our protection. A few soldiers went to the abandoned bunkers without Zeerakee's permission and brought back a few plates and a log; as we say they carried out a "tack". Hearing of these bold moves, Zeerakee sent a group of soldiers to bring back more materials. He even grew bolder and decided to destroy all the bunkers and bring everything once and for all.

One day at sunset he took fifty soldiers and set out for the bunkers. They destroyed most of them and started carrying the boards, logs, and plates. Half way across, the shining metal plates reflected sunshine towards Iraqi positions. The sun was nearly setting and Iraqis had the best observation; and they spotted them. They took it for an Iranian evening invasion and bombarded them with 120mm mortar shells. Assuming there was larger number of forces behind the hill, they stretched their range up to our platoon. A shell landed near one of our bunkers and wounded four soldiers. Two received golden shrapnel (21); but two were seriously wounded. They are still in the hospital. I think after that Iraqis planted mines in and around the bunkers to catch our soldiers if they went to bring more logs and plates."

A couple of weeks later I saw one of the hospitalized soldiers: Ghodrat Raheemee, back in the platoon. He had received a large piece of metal in his neck near his throat. The metal had been left beneath the skin to dig its way out.

"What happened to the other one?" I asked Ghodrat as I was touching the shrapnel.

"He was hit in his spinal cord," Ghodrat replied sadly, "He is paralyzed and is still in the hospital."

With the disaster of January 5, 1987, the dread of mines began haunting me. When one of Lieutenant Assadi's soldiers lost a foot to a mine, my dread grew to the level of a nightmare. In my area there were hundreds of mines that could take their toll of my soldiers' limbs. Although these mines were not of Valmeri type, I had to find a solution for the problems they posed. Their planting in that area had a story different from those near the Iraqi bunkers.

When Iraqis had the area under occupation, they had scattered those mines randomly with rolls and rolls of barbwire in front of the hill facing east to defend it against Iranian parachutists or helicopter-borne forces. In an area about three square-kilometers they had left four narrow paths for their sentries to descend to the foot of the hill to monitor the possible approaching of Iranian forces. Now, a few years later, Iranians had the hill. Iraqis' former front line was behind us and, indeed, we were hiding ourselves from their observation and shells among the mines that they had scattered. Of the whole mined area about one square kilometer was my share.

My mines were anti-personnel; I believed they had been made either in Italy or in Germany. They were as big as a small fish can; their color was khaki: exactly the color of the surrounding sand with a little black rubber pedal visible on the top. If someone pressed the pedal, a tiny needle that had been attached to the lower side of the pedal would touch a fuse in the bottom of the container and would explode the TNT and the container together. There was no pellets or other kinds of metal fragments in them. They were not powerful enough to kill, but they could easily sever a foot or a leg.

It was dangerous to move among mines in the narrow paths that were easily lost due to the moving sand and the darkness of nights. Removing them seemed to be the only way to permanently get rid of them. To do this, we should have known their distribution plan, their exact type, ways they exploded, and whether they were trapped or not. We needed a mine detector to locate the precise place of each and every mine.

Our most important limitation in dealing with the problem was that the mines had no specific distribution plan that we could discover by following patterns and contemplating on them. The moving sand might have covered some of them; or it might have entirely changed their location. There was an uncertainty about the type of the mines as well. We could not tell with certainty whether the visible mines were the only ones in the field. We knew that, almost always, different kinds of mines and traps were used in one minefield to deter different combination of forces and movements.

Of mine detectors we had none. It was too expensive to provide every platoon with a mine detector, though possibly the engineering units of the battalion or the regiment had a few at their disposal. Even if available, a mine detector would be useless as the mines had been almost wholly made out of plastic except for the tiny needle and the fuse: too little to be detected. In addition, there were many pieces of shrapnel, cartridges, bullets, and other metal fragments of the bombs scattered over the area. They could constantly set off the detector's alarm without detecting mines.

Combination of these factors made the job very risky. It required a strong morale and a certain amount of foolhardiness to deal with them. I had such a fear of mines that I never dared go near them. Just looking at them made me uneasy, leave alone touching them. But as time advanced and I grew bolder with explosives, I took shelter behind a mound and shot at a mine from a long distance. I hoped to explode them in this way and enjoy the risky game; however any time I hit one it would simply shatter or would lose a chunk of it. In brief, I failed to explode any of the mines.

One day Abbasspour told me he could disarm mines and asked my permission to show me how. Having shuddered with fear, I denied permission; but he was not going to give up. He told me the explosive inside the mine could be burned without exploding. I had never seen the explosive to be burned. I always thought explosives would explode when exposed to any element of heart, force, or electricity. Once again he asked me to let him show me how he disarmed a mine. This time I agreed with one condition: I stayed beside him while he worked on a mine. I wanted to equally share his suffering if a mine exploded.

We went to the minefield near our bunker and found a mine near the path. Abbasspour walked to it without any fear as I grabbed his shirt and pulled him aback. That much carelessness was not admissible. I told him to use his bayonet to examine the soil to make sure there was no mine under the ground in front of the one he was trying to reach. While he was assuring me there was no danger to walk straight to that mine he took my advice and examined every inch of the place. At last, he reached the mine. Once again I told him to make sure it was not trapped. He almost burst to laughter at my untried goat-heartedness saying that type of mine had no spot to be trapped. Nevertheless, he dug around and beneath the mine as I had ordered which took him several minutes.

When he reached his hand to grab the mine, I was so scared that I felt my feet were trembling beneath me. He took the mine without mishap and walked out of the field. Unscrewing the fuse at the bottom, Abbasspour removed a round piece of pink explosive with a hole in the middle and handed it to me. We threw the TNT to our evening tea fire and with my surprise it burned with an intense yellow and orange flame.

After Abbasspour's experience I grew bolder. In few instances I disarmed a few mines myself dispelling my fear; but, the field remained a frightening obsession and I spent a long time to find a permanent solution for it. Sometimes, in the middle of my decision-making process I told myself:

"Don't be stupid. If a mine explodes, it will cost you at least a limb. You must be out of your right mind to lose a limb in this damned war."

After a bitter struggle I decided to collect the mines whatever the price. I resolved that if there were a price to be paid, I must be the first one to pay it. On the determined evening I chose six soldiers to make a line across the field and walk forward alongside me with myself in the middle. They were not to touch the mines they saw; they were to stay beside it and call me to pick it up. In this way we inched our way deep into the field. The soldiers carefully carried out my order and I gathered the mines one by one. So far, I had put aside more than ten mines without a mishap.

Now, I had two mines in my hand and was putting my foot near a third one. As my right toe touched the ground Khodadad Zand-e Lashanee shouted from behind my back. I froze: with my toe on the ground and my heel in the air. I looked over my shoulder to see the source of the voice.

Khodadad's mouth was wide open.

"What happened?" I asked calmly, but frightened.

"Don't move," he said, "Just look beneath your heel."

There was a mine under my right heel. Shifting my foot, I picked it up with many thanks to Khodadad.

Thus, I swapped the minefield. We kept our collection in a safe place for a few days. Then, we planted them in a place where enemy penetration was probable and encircled them with the Iraqi abandoned barbwires. The question of mines was solved, though I faced Captain Jalalee's criticism.

On his first visit to the front Jalalee was in Zeerakee's bunker. It was a Friday morning. Neekvarz was on leave and Zeerakee was back to the front line. Fridays were always quiet. As a respect for the Islamic weekend, there was an un-written convention of ceasefire between the two sides. If there were any violation, it was the Iranian side that initiated it. Taking advantage of the calm, I was washing my laundry when Abbasspour told me I was wanted in Zeerakee's bunker. He said Zeerakee wanted to introduce me to the commander of the battalion who was visiting the front line. I washed my hands, put my helmet on, took my rifle and walked to the commanding bunker.

Upon entering I saw Zeerakee in his best military uniform with a clean green kerchief around his neck and a wide smile on his face. Beside him a middle-aged man with broad shoulders and slightly protruded stomach sitting on Zeerakee's couch stood to his feet, shook my hand, and in a hasty tone introduced himself as Captain Jalalee. It appeared to me that he did not expect to see me in my full combat gears, as officers normally did not wear them.

After I sat at their invitation, Jalalee asked what was going on in my area. I gave a short verbal report and complained about our inadequate food, poor sanitary situations, and the dire state of our combat equipments. Jalalee skillfully digressed what I had raised by saying he had heard about my work on the mines. In his view mines were dangerous and I was not allowed to change their location that had been determined by the platoon of combat engineering.

"At the end of the war they have to clear the minefields according to the distribution charts they have," he added, "This time I overlook what you have done. I hope I won't see it repeated."

Jalalee paused a bit, searching for a proper start to express an important thought.

"Sometimes, my family and friends ask me if I have ever killed anybody at war," he resumed thoughtfully, "It is a hard question to answer; and I have always replied that I have never committed homicide. It is simply because I don't see enemy forces to shoot at them myself. But when I muse on the question, I find that I commit homicide too. Artillery, mortar, and infantry forces operate at my command. I order them to bomb; I order them to attack; and if during these operations someone gets killed, I have committed it. Probably the better title for me as commander of more than one thousand combatants is the "ringleader of criminals".

Of course, our crimes are legitimate. I mean nobody persecutes us for committing them; otherwise, I don't see any moral or humane legitimacy in them. Our immunity from persecution is because we operate at the command of super-killers. Let's avoid philosophical debates," he sneered at what he said last.

"It is what it is Brother; we cannot change it," he said and burst into laughter leaving me baffled and thoughtful.

I was stunned at the professional soldier's brutally honest admission. A challenge of contradictions was in this high-ranking officer's outspokenness: a confrontation between what his military career dictated and what his conscience was telling his heart. He badly needed to justify himself to his conscience and to the listener, but could find only the weak argument that since war had been practiced from the beginning of history, perhaps his fighting was justifiable. This reconciliation made only a fragile peace between the two striving feelings. Any impetus could renew the challenge and keep it going, probably, as long as he lived. This bitter strife was shared by thousands of warriors: the uniformed men who could find no justification for fighting. Once I wondered if the warmongers, arm-producers, and arms-dealers had ever faced such a challenge; and if they had, had they ever thought of sacrificing their profits for the sake of peace and a clear conscience?

| Recently by Manoucher Avaznia | Comments | Date |

|---|---|---|

زیر و زبر | 6 | Nov 11, 2012 |

مگس | - | Nov 03, 2012 |

شیرین کار | - | Oct 21, 2012 |

RECENT COMMENTS

IRANIANS OF THE DAY

| Person | About | Day |

|---|---|---|

| نسرین ستوده: زندانی روز | Dec 04 | |

| Saeed Malekpour: Prisoner of the day | Lawyer says death sentence suspended | Dec 03 |

| Majid Tavakoli: Prisoner of the day | Iterview with mother | Dec 02 |

| احسان نراقی: جامعه شناس و نویسنده ۱۳۰۵-۱۳۹۱ | Dec 02 | |

| Nasrin Sotoudeh: Prisoner of the day | 46 days on hunger strike | Dec 01 |

| Nasrin Sotoudeh: Graffiti | In Barcelona | Nov 30 |

| گوهر عشقی: مادر ستار بهشتی | Nov 30 | |

| Abdollah Momeni: Prisoner of the day | Activist denied leave and family visits for 1.5 years | Nov 30 |

| محمد کلالی: یکی از حمله کنندگان به سفارت ایران در برلین | Nov 29 | |

| Habibollah Golparipour: Prisoner of the day | Kurdish Activist on Death Row | Nov 28 |

fascinating

by Jeesh Daram on Sat Nov 10, 2007 10:56 AM PSTRare in our libraries are books about individual's first hand memoir of horrific war scenes. This is a strong story, pulling the reader inside to find out and better understand the psyche of the men in war, an imposed war that could have not had a true victory for either side....

Great job.