به زبان فارسی

PICTORY

LATEST MUSIC

SEARCH

The Secret Agent

by Ari Siletz

03-Apr-2009

Some months before he vanished, Golbaz had said something about a new law about to be passed that would affect his job. Soon he started skipping town on short notice for days at a time, sometimes coming home with a tan, sometimes having lost weight. He wouldn’t say where he had been. Until one day Aunt Merhri found airplane tickets in his jacket. “When were you going to tell me?” she fumed. “At the last minute.” he replied. He was going to Europe for training, but wasn’t allowed to say more. Aunt Mehri showed me Golbaz’s letters. They were dated a week apart from London, Paris, Munich, Amsterdam, Vienna, and some cities I hadn’t heard of. There were no return addresses, and gave no clues as to what he was doing or when he might return.

Six months later he came home, but stayed for just a few weeks. One night he said he would be gone for another three maybe four months and not to expect any communication from him. This time Aunt Mehri wouldn’t let him go out the door without some explanation, or at least some way to reach him. They had such a big fight, the neighbors rushed in to restrain Aunt Mehri. She was smashing windows. She cursed Golbaz to Hell in front of the whole neighborhood, spat at him, and told him she hoped he would never come back. Then she threw his luggage out of the house, while he still begged, promising to explain when it was over.

The last words he spoke to her were through the door: “I have arranged for my paychecks to be payable to you.”

After months of Golbaz being overdue, Aunt Mehri started asking after him. The Justice Ministry would say only that the mission had been extended. They asked her to stay away until she heard from them. But she kept going back. Every week at first, then every day, until one morning a one-line letter arrived in Golbaz’s handwriting. It said, “I’ll be home soon.” I saw the letter. The stamp had a picture of the Shah. He was in Iran, most likely Isfahan by the barely legible postmark.

She redecorated the house for his return, vowing she would never be cross with him again, not matter what. She even planted a citrus in the tiny garden because she knew he liked the scent. On a soft spring afternoon came a familiar knock. She rushed joyfully to the door, kissing the air as she ran.

But on the doorstep stood a small man in a crumpled suit with no tie and a stubbled face. He was a gofer with instructions to drive her to the Justice Ministry building. In the lobby, he offered her a seat and asked her to wait. Quickly a server brought her a glass of tea and a few lumps of sugar. Her tea still untouched, a pleasant spoken lady introduced herself as the private secretary to the minister. She took Aunt Mehri to a top floor office where the minister himself gave her the sad news. Detective Golbaz’s remains had washed ashore to the banks of the Zayandeh River in Isfahan.

At the gate, I made sure the ritual of my parting with Aunt Mehri lasted a long time, filled with promises of future visits. The citrus trees in her yard had blossomed. I took the time to smell the flowers and comment on their fragrance. She had tears on her face as we hugged and kissed goodbye. Then I stepped across the threshold through which she had evicted love--in the time before I was born.

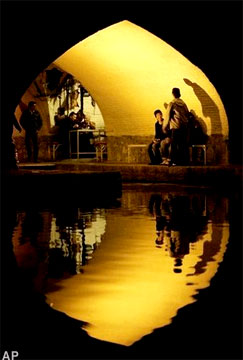

It took life three years to put me on the banks of the Zayandeh River. During those years I traveled far from Iran to many of the cities from which Golbaz had written to his wife. On the bridges over the Thames, the Seine, the Danube I had promised myself that if ever I stood over the Zayandeh, I would float flowers on her waters.

I was now seventeen. We were all seventeen, more or less. A rowdy bunch of high school brats packed in a tour bus on a field trip to historic Isfahan. We had already covered the usual attractions, palaces, mosques, wiggling minarets, and a bazaar that burrowed into the old city like an unending tunnel of treasure. Now, for something different, we were crossing the centuries old Khajou Bridge to a place not on tour guide maps.

It was the history teacher’s idea to mar the glitter of Isfahan by dissecting its smelly underbelly. His name was Dr. Parson, a dangerous Marxist armed with a passport and an Oxford degree. His post-doctoral mission was to travel the world disillusioning bourgeois high school students. Leftist ideology was to blame for this grim visit to Isfahan’s drug rehab hospital.

Listening to me grumble was our soccer team captain, Fournier, the son of a French diplomat working in Tehran. His accent demoted Parson’s name to rhyme with the French “garcon.” Fournier was tuning me out with a comb, musically running a fingernail over the teeth. Across the aisle, sat Lina, the daughter of a Swedish archeologist couple digging in southern Iran. My incessant groaning must have thrown Fournier off his game; ordinarily he would never let an attractive girl see his grooming aids. We were Iranians, Americans, Swedes, French, Turks, Greeks, many of us moaning in a Babel of disgruntlement.

As the bus unloaded at the asylum, an upbeat Dr. Nojoom, welcomed the group to the bleak institution. The fortyish director looked too stylish for the drab occasion. He had dressed for a classier crowd. Nevertheless he was thrilled at the opportunity to address such a large group of international visitors. And he lectured tiresomely on his socially indispensable facility. No doubt, his report to the Health Ministry would brag about international students learning his techniques. There would be no mention, of course, of the scholarly giggling triggered by Nojoom’s over estimation of our importance. Lina and Fournier were the only ones politely taking notes. The embarrassed Dr. Parson, labored to contain our rudeness, several times referencing Oxford to give Dr. Nojoom’s report a consolation prize.

Thanks to Parson’s idea of a fun Isfahan trip, we now knew that out of every one hundred addicts treated at that facility only sixty returned. The other forty, who were never heard from again, had presumably recovered. After the stats and graphs ceremony, Dr. Nojoom guided us along a dank hallway to a door with large frosted glass windows.

Human shaped shadows crowded the frosted glass. Tortured forms wriggled and convulsed like a school of fish suffocating in murky waters. Abruptly, a sense of dread cast an oppressive hush over the crowd. The agony on the other side of that glass knocked the arrogance out of us like a harsh slap across the face. Parson had delivered his gloomy lesson.

Lina, standing next to me, looked away as Dr. Nojoom opened the door. From the end of our row, Fournier gestured me to keep an eye on her. An oppressive stench of sweat and stale cigarette smoke tumbled out the room. The smoke was so thick that the wriggling forms looked no clearer than they did through the frosted glass. A ghost floating through the smoke approached us, pained and skeletal. It stared voicelessly as a drool of smoke drifted from its face. Briefly its mouth glowed a bright red then dimmed. Before I could make out a human face he turned around and dissolved back into the shadows.

The ghost lingered in my mind, a morbidly seductive image. It was as though, I was walking past a graveyard and my name had been called. Lina’s voice brought me back from the gloomy gates. “It looks like Hell in there,” she said, obviously horrified by the scene. She was speaking for everyone.

“Young lady,” replied Dr. Nojoom. “There are exactly forty hells in that room, and at the other end of the hall, forty more.”

Lina understood his meaning. “But why is narcotics withdrawal so painful?” She asked.

Dr. Nojoom, flattered by the beautiful girl’s willingness to jot down his every word, waxed philosophical. “It’s the price we pay for a glimpse of heaven.”

She started to write it down, catching herself part way. “Is it worth it?” She asked not too rhetorically.

Dr. Nojoom exchanged adult glances with Dr. Parson. Then Parson spoke for Nojoom. “They would go through a hundred times worse for just one more fix.”

“Well said! A brilliant way to put it, Dr. Parson,” Nojoom beamed. “But please ask them yourselves. You are welcome to go in and talk with the patients. It would be good for them. Just don’t give them money if the ask.”

None of us, not even the unflappable Fournier, felt like going into that room, much less talking to the inmates. As each tried to move to the security of the center, the crowd began to slither formlessly away. At the corridor exit, a feeling tapped me on the shoulder making me take one last look in the direction of the room. The tall ghost had come to the fore again, staring with its huge dark eyes. Suddenly my mind caught up with that elusive call from the graveyard. It was recognition. I had seen that face many times in picture frames.

I detached myself from my classmates and approached him. He retreated. I followed across the threshold through the thick smoke, and finally cornered him as he pressed himself against a barred window at the far end of the ward. “Excuse me, I said in Farsi, “I’m a high school student from Tehran. Dr. Nojoom said we are allowed to talk to you.”

The man held his stare steadily out the window.

“How long have you been in this institution?”

Not a word. He didn’t seem to hear me.

“Is your methadone substitute as good as heroin?” I was starting to gag from the smoke and sweat. Finally I said, “Sir, would you by any chance be related to a gentleman by the name of Golbaz?”

Suddenly, he turned around and looked at me like I was the ghost. His knees gave out from under him. Scrambling up like a dog on ice, he scurried on all fours to the nearest cot, and quickly pulled a blanket over his head. Was this a reaction to my question, or just the paranoia of a heroin addict? I treaded hurriedly out of the ward, feeling like a museum patron who had just tipped over a vase.

I told myself that driving across the Zayandeh had triggered this fantasy. Golbaz’s soul, damned by Aunt Mehri’s curse, had wafted up from the river, and seeing the suffering inside these walls, had mistaken the place for Hell. But even if Golbaz’s ghost was still haunting the living, this creature couldn’t be it, because ghosts don’t age, and this man looked at least 15 years older than the photos I had seen of Golbaz.

I caught up with the others back in the cafeteria where everyone was asking their final questions. The students, still smarting from Parson’s kick in the pants out to reality, were now curious about the anguish they had just witnessed. Fournier made his way to me in the crowd. “What ‘appened to you? You’re white as an Aspirin pill.”

“Not now Fournier,” I said.

“Where ‘ave you been?” He said. Too preoccupied to answer him, I raised my hand and asked out of turn if a record is kept of the backgrounds of the patients.

“Of course,” said Dr. Nojoom.

“Can we see one of those records?” I pressed.

Dr. Nojoom’s brows furled. His eager oiliness and servile hospitality suddenly a calculating stare. Before he could say ‘no,’ an orderly rushed in and whispered to him. Dr. Nojoom took another distrustful look at me and said to everyone, “I’ll be just a minute.”>>>Part 3

| Recently by Ari Siletz | Comments | Date |

|---|---|---|

چرا مصدق آسوده نمی خوابد. | 8 | Aug 17, 2012 |

| This blog makes me a plagarist | 2 | Aug 16, 2012 |

| Double standards outside the boxing ring | 6 | Aug 12, 2012 |

RECENT COMMENTS

IRANIANS OF THE DAY

| Person | About | Day |

|---|---|---|

| نسرین ستوده: زندانی روز | Dec 04 | |

| Saeed Malekpour: Prisoner of the day | Lawyer says death sentence suspended | Dec 03 |

| Majid Tavakoli: Prisoner of the day | Iterview with mother | Dec 02 |

| احسان نراقی: جامعه شناس و نویسنده ۱۳۰۵-۱۳۹۱ | Dec 02 | |

| Nasrin Sotoudeh: Prisoner of the day | 46 days on hunger strike | Dec 01 |

| Nasrin Sotoudeh: Graffiti | In Barcelona | Nov 30 |

| گوهر عشقی: مادر ستار بهشتی | Nov 30 | |

| Abdollah Momeni: Prisoner of the day | Activist denied leave and family visits for 1.5 years | Nov 30 |

| محمد کلالی: یکی از حمله کنندگان به سفارت ایران در برلین | Nov 29 | |

| Habibollah Golparipour: Prisoner of the day | Kurdish Activist on Death Row | Nov 28 |

Thanks ramintork

by Ari Siletz on Thu Apr 09, 2009 12:39 PM PDTstill with it!

by ramintork on Wed Apr 08, 2009 01:51 PM PDTStill following!

Diesel Damsel

by Ari Siletz on Sat Apr 04, 2009 11:20 AM PDTGood question about the non-Iranian characters. They do become important actors in the plot, and to some extent participate in symbolisms. Good call though. Whether I have been able to sufficiently work them into the soul of the story is something for Diesel Damsels to judge and comment on.

On the maturity issue, the suspension of disbelief about maturely observant children is a cultural matter. The Iranian reader would resist imagining Khaaghaani as a teenager. The western reader however has no trouble with Byron having published these khaaghaaniesque verses when he was only fourteen:

Through the cracks in these battlements loud the winds whistle,

For the hall of my fathers is gone to decay;

And in yon once gay garden the hemlock and thistle

Have choak'd up the rose, which late bloom'd in the way.

The narrator and the reader

by Diesel Damsel (not verified) on Sat Apr 04, 2009 01:31 AM PDTIn fact the narrator's age, his observations vis a vis his experiences, or even his language are somewhat immaterial to a good story. The reader knows already that a 17-year old boy did not write this story, therefore to examine what the 17-year old knew or didn't know at the time of the story is irrelevant.

If we must, then the reader remembers that this particualr young man has been somewhat preoccupied by the forbidden story of a missing relative since he was a child. The reader already knows that the narrator was obsessed by the combination of secrecy about the character, the "facts" as presented by Aunt Mehri, the farfetched tale told by the old Tooba, and the "evidence" he had collected in his mind about Golbaz. It was to be expected that his visit to Zayandeh Rood would trigger his haphazard collection of personal observations and tales intermingled with fantasies.

What is intriguing is the almost-but-not-quite-as-yet realization of those fantasies. It is likely that the narrator's imagination wished to locate the missing relative in the vicinity of his last known locale; but when signs and sights in the assylum further direct him toward that realization the story becomes fascinating.

You are building a most complicated tale, Mr. Siletz, and I had to go back and read headers to both parts to make sure this was not a part of your jinn stories. Is it? Also, is there relevance to the non-Iranian characters' presence at the scene, except to suggest a reason for the narrator's otherwise unlikely appearance at the assylum?

A very good story, just the same. Thank you.

IRANdokht, preview:

by Ari Siletz on Fri Apr 03, 2009 04:10 PM PDT“Maybe they’re orderlies from the mental institution,” I said. “So what if they’re moonlighting.”

“Body guards,” Fournier whispered.

“ Don’t joke.”

Fournier put his hands under the table and pointed out the one wearing a white jacket. Then he mouthed the word, “G U N.”

*************************** On the child maturity issue in literature, here's 6-8 year old narrator Scout Finch in To Kill a Mockingbird: "Slowly but surely I began to see the pattern of questions: from questions that Mr.Gilmer did not deem sufficiently irrelevant or immaterial to object to, Atticus was quietly building up before the jury the picture of the Ewell's home life."Child narrators are often emotionally precocious. However, an excellent example of a character which manages (barely) to pull it off as an emotionally immature teenager is Cher Horowitz in the film Clueless.

Ari jan

by IRANdokht on Fri Apr 03, 2009 03:24 PM PDTBy mature I meant the capacity of uderstanding other people's feelings and how observant he is. I know grown ups who do not read facial expressions or do not listen to the details like the citrus tree for example, to actually notice its smell later when he passed by it.

The details are so complete that I was actually shocked to read how old he was when he went to Esfehan. I had to do a double take and read it again.

So where is the preview? :o)

IRANdokht

IRANdokht

by Ari Siletz on Fri Apr 03, 2009 11:40 AM PDTRegarding maturity, I think various generations (youth or adults) are mature in different ways. Alexander the Great expertly took on the responsibilities of state at sixteen, something unthinkable to a modern sixteen year old. Yet the modern teenager has probably seen more of the planet than the globe trotting Alexander ever did. And I will point at--but not open-- the can of worms which is the modern youth's sexual savvy.

that's so cruel!!

by IRANdokht on Fri Apr 03, 2009 10:14 AM PDTI want to know what happens next! don't leave me hanging here Ari!!!

;-)

I just couldn't stop reading! I love the way you describe feelings through visuals:

...a feeling tapped me on the shoulder making me take one last look

She rushed joyfully to the door, kissing the air as she ran.

I stepped across the threshold through which she had evicted love.

What a great story! Love, suspense, drama... all intertwined skillfully.

Your protagonist seemed too mature for a teenager, too observant and considerate. Then I remembered, that's the way it was a couple of generations ago, wasn't it? Kids matured a lot earlier back then and it's not fair to compare him to today's teenagers.

I was going to save my comments until I read the last part but you didn't let me! I can't wait to find out what happens next.

IRANdokht