به زبان فارسی

PICTORY

LATEST MUSIC

SEARCH

Yes We Should

by Sussan Tahmasebi

31-Aug-2010

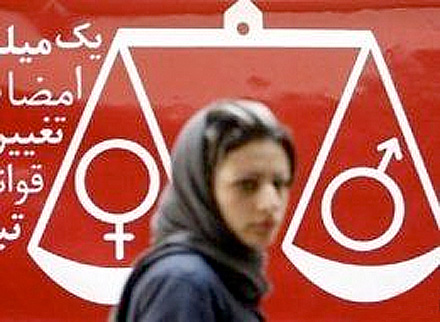

When we first started the One Million Signatures Campaign, we realized that the effort was unique. We were intent on raising awareness about women’s rights and the impact of laws that discriminate against women at the grassroots level by engaging in face to face discussions with ordinary citizens. At the same time, we realized that the Campaign would serve as a valuable experience for activists as well, who would be afforded the opportunity to learn from citizens and especially from women. We hoped the experience of these face to face discussions would allow us to amplify the voices of women and reflect their concerns. Further, we realized and hoped that the Campaign would serve a catalytic role in engaging a whole new generation of activists interested and concerned about women’s issues who had remained on the sidelines of the fight for equality. We hoped that the Campaign would be able to provide a space for the activism of a younger generation of Iranian women and offer an opportunity for training and empowerment of a new generation of women’s rights activists, who benefiting from access to higher education, could not coalesce the dichotomous nature of their status in society—second status as defined by the law and rapid upward mobility resulting from social and educational advancement of their generation.

In reality and as it turned out, the Campaign opened the floodgates of activism on behalf of women’s rights, not only for younger women, but also for an older generation of women, who had never engaged in social activism or who disenchanted by the prospects for change had withdrawn from the social sphere long ago. These older women joining the Campaign had however experienced in their personal lives the challenges of living in a patriarchal society and had quietly suffered or witnessed the suffering of other women which results from the imbalance of power and the inequalities promoted by law. The Campaign too provided an opportunity for men to become active and lend their support to the women’s movement, especially young men, who felt that gender equality was a prerequisite to a democratic and just society. Reaching beyond borders, the Campaign has also served a catalytic role in connecting women’s rights activists in Iran, to women’s rights activists in the Diaspora, bridging the divide of space, time, ideology, experience and background.

From the start, activists began writing about their experiences of engaging in face to face discussions with fellow citizens and collection of signatures in support of the Campaign’s petition. By harnessing the power of the internet, the only form of broad communication available to the Campaign, we began to reflect these experiences in almost real time. The translated writings which appear on the English site of the Campaign represent a small selection of nearly 300 pieces written by activists and published in the Face to Face section of the website Change for Equality, which is published in Farsi.

Face-to-Face Engagement an Experiment for Empowerment

These personal accounts reflect in the first instance the process of empowerment of activists, resulting from their agency—an agency that is civil in nature, proactive and positive. The process of empowerment as reflected in these personal accounts usually entails a decision to take concrete action to improve ones own condition and to invite others to take action, either through a simple signature in support of the petition of the Campaign or further involvement in this broad effort. Countless activists, many of them entering the Iranian women’s movement through the Campaign, have discussed the self confidence they have gained through the experience of engaging with fellow citizens—a self confidence that comes from putting your beliefs to the test, being able to support your aims through dialogue and discussion, and inviting others to take action. What has also been a positive aspect of this empowerment has been the unique opportunity of three generations of women, with differing levels of experience, working side by side and learning from one another. The unique characteristics of the Campaign within the context of Iranian history, has created an opportunity for women from differing backgrounds, different ideologies and political beliefs and different generations to work and learn along side one another. Here no one can claim to have the greater experience. Each generation brings with it unique and valuable skills and perspectives, adding to the diversity and impact of the Campaign.

Interestingly enough, activists who set out to collect signatures for the petition of the Campaign, have in these writings pointed to the fact that they usually start with their immediate circle of friends and family. Besides being a logical starting point for action, this approach speaks of the need for activists to gain the moral support of those closest to them and to gauge their level of commitment to a cause and the realization of a goal for which activists are willing to pay a high price. Also, starting from what is familiar, provides activists the opportunity for trial and error—an activity that helps build confidence in the difficult task of approaching strangers on the street, with whom they may have little in common.

Additionally, the pressures that activists involved in the Campaign have felt from the start too may have something to do with the value placed on this aim. How much support will I receive if I were to be arrested? No doubt, this possibly is an underlying question behind the efforts of activists to get their friends and family to support the Campaign as well. While in these writings few address the stress and concerns of this type of public action, which may end in arrest, in private discussions the fear and concern is prevalent and readily sensed.

Amplifying Women’s Voices

In these accounts too, activists have relayed their discussions with women they approach. These activists have used the forum provided to them by the Campaign to tell the story of the pains women have suffered as a result of unjust laws—stories and tales, struggles and woes which may go unnoticed or untold otherwise. Dealing with the agony caused by a polygamist husband, the loss of custody of children as a result of divorce, the long struggle to obtain divorce, dealing with violence, etc., these accounts have all been documented by writers of the Face to Face Section of the Change for Equality website, serving as tangible supporting evidence to the need to change discriminatory laws. Writers in these tales relay the process of connecting with ordinary citizens and developing relations of trust and by retelling the stories of ordinary women these activists demonstrate their commitment to amplifying the voices of women who have little recourse in their struggle for justice.

At the same time, these accounts point to two contradicting trends in Iranian society, as demonstrated by the reaction of those approached to sign the petition of the Campaign. First is the fact that social advancements and cultural norms outdate and are far ahead of the existing laws. Those who fall into this category tend to support the Campaign’s petition by signing it or becoming more actively involved. To the pleasant surprise of activists on occasion they encounter citizens who have already signed the petition or who have heard of the effort and had been waiting to join in some way. Then there is the second group, who still does not believe in the legal equality of men and women. These individuals can sometimes be convinced to support the Campaign’s demands through tangible examples provided by activists, but there are others who hold firmly to their patriarchal beliefs, driving home the point that awareness raising is as important, if not more important a goal as signature collection.

Documenting Developments in the Women’s Movement and Strategizing around Security Pressures

There are indirect results to this process of documenting face to face experiences which are remarkable in and of themselves. In the first instance, this effort has worked to document the developments in the Campaign and therefore the Iranian women’s movement. While one can claim that the site of Change for Equality, and other sites related to the Campaign have all worked to document the developments in this broad and significant effort within the larger Iranian women’s movement in an unparalleled manner, the Face to Face section of the site, because of the breadth of writers and stories and its sheer volume is noteworthy in and of itself. If examined chronologically these writings shed light on developments within the Campaign, both the personal developments I have addressed above including the building of skills among a new generation of women’s rights activists, but also developments in the women’s movement. For example, a chronological examination of these writings points to the ebbs and flows within the Campaign, periods of pressure, the negative impact of security pressures in limiting and constraining signature collection efforts, and the innovative responses by Campaign activists who have consistently worked to multiply their points of impact, when faced with security pressures and limitations.

While signature collection was first introduced and mainly promoted as a door-to-door activity, it soon became apparent that with security pressures and the possibility of arrest it was not possible to carryout door to door initiatives broadly and with great freedom and security, so activists focused more of their efforts on private gatherings. Realizing that this approach had its limits—focusing on immediate circles most accessible to activists—Campaign activists decided that their presence in the public sphere was indeed necessary to bring about the cultural and legal changes desired. While the women’s movement in Iran has for nearly a decade now actively discussed strategies for street politics, including protest, it has never been successful in carrying out a sustained presence in the public sphere—that is until the Campaign. The Campaign is the first initiative to be first and foremost focused on the public sphere as its point of impact. Given the un-treaded nature of such an approach and the security pressures on the Campaign as well as limitations imposed by the prospects of arrest, but the commitment of maintaining a strong presence in the public sphere and on the streets, activists focused their signature collection efforts on public spaces where women could be found, such as the transportation system, open markets, and shopping centers. Further in an effort to support younger activists who may be arrested during signature collection, the Mothers Committee made up of older activists was formed and signature collection of younger activists was coupled with the older activists. More experienced activists also began to partner with newer volunteers. In the end, and through a process of trial and error intent of centralizing and prioritizing our presence in the public sphere, and identifying new and alternative spaces group signature collection drives were initiated. While these collections were at first limited to smaller circles of friends and colleagues working in the Campaign, in time mechanisms were established to broaden the scope and invite new and old activists to take part. Those interested in group signature drives could connect with one another to set up a time and place to meet, through an email listserve, making the process of networking, sharing of experiences in the network of the Campaign, a horizontal, peer-to-peer, un-facilitated and immediate process. The process worked so well that it served as a new form of organizing the activities of the Campaign for some time. But still with the arrest of several members during one group signature drive, activists once again began to work in small groups.

Despite the intensification of pressures on activists and Iranian society as a whole following the disputed Presidential elections in June 2009, signature collection is still carried out in small groups. But to address the need for broader awareness raising activists have focused a considerable amount of attention on holding small workshops as well. In the past year alone, over 400 persons were trained in a variety of issues related to women’s rights, including on the Campaign and how to collect signatures.

Another important aspect of the Face-to-Face section of the website of Change for Equality has been the medium it has provided for expression of support for those who are arrested in relation to their activities in the Campaign. These personal and often emotional accounts in support of imprisoned friends and colleagues, have served as a strategy for defending our common cause and insisting on the legitimacy of the Campaign’s goals and strategies. At the same time, these writings worked to raise awareness about the situation of activists inside prison, and to maintain their presence in the news media. The most difficult but important task when an effort faces crackdown is demonstrating support for those imprisoned and keeping the focus of the media on those who are unjustly imprisoned. In other words, keeping the memory of those in prison alive and ensuring that others in the movement remain committed to the cause. We see now, that many other groups, including journalists, political activists, human rights activists, student activists, etc, who have faced increased crackdowns in the last year, too have utilized this technique which was born out of the necessity of keeping Campaign activists in the news and brining attention to the pressures and arrest of younger and lesser known activists.

Activists who were imprisoned too came in direct contact with female prisoners, many of whom had faced challenges posed by discrimination and discriminatory laws, which contributed significantly to their incarceration. Several of these activists decided to write about the women they met in prison and how these encounters strengthened their resolve to continue on with their struggle for equality. Some of these writings were dictated by phone to colleagues outside prison, bringing attention to the need to change discriminatory laws and much publicity for the cause of the Campaign as well.

Providing Space for New and Young Activists

A cursory examination of the backgrounds of Campaign activists demonstrates that they are largely new to the field of women’s rights activism. Many had tried in the past to enter the women’s movement, but were unable to connect with women’s NGOs or found those NGOs unable to absorb new volunteers. Some NGOs, based on written or unspoken policies, remained relatively closed to the participation of younger and unknown activists, prior to the start of the Campaign. Many of the younger activists involved in the Campaign did come to this movement after being involved in the student movement, but they too lament that the space provided in the University had often been less than receptive to their attempts at raising the subject of women’s rights or even less encompassing issues related to female university students. As such, the Campaign provided an opportunity for a whole new generation of women’s rights activists to begin their activism on behalf of their legal demands.

The site of Change for Equality, by providing space and by publishing writings of younger activists, took solid steps toward breaking the hegemony of the small number of women’s rights activists who had received exposure through their writings in reformist publications, women’s publication and websites related to women’s issues. In so doing, this site has given visibility and voice to unknown but impassioned activists with much to say. The Face to Face section of the Campaign’s website in particular has played an important role in breaking this hegemony. The simple and straightforward nature of the writings in this section work to promote a desire for writing rather than dissuade new writers and activists from relaying their experiences and ideas. The breadth of writings in this section and the range of new writers and activists who have utilized this medium to express their concerns and to relay their experiences are proof enough that the women’s movement is much broader than the few who had in the past had the opportunity to write and be published.

Likewise, this trend has worked to break the hegemony of a small group of activists and writers who through their writings and connections had managed to gain international acclaim. For the first time, a group of relatively internationally unknown younger activists participated in AWID’s international forum in Cape Town, South Africa, November 2008, where they had the opportunity to present on the work of the Campaign. One international women’s rights activist correctly noted that "while we have been discussing for years the concept of participatory and inclusive leadership in our women’s movements, the activists in the One Million Signatures Campaign in Iran have accomplished this goal.” Still the Campaign has a long way to go in terms of breaking the hegemony of some better known women’s rights activists nationally and internationally, but it has taken solid and positive steps in opening up this space for younger and newer activists, and promises to hold lessons for women’s rights groups nationally and internationally.

The Future of the Campaign in an new Political and Social Environment

With the migration of several well known women’s rights activists in the past year from Iran, much has been said about the crisis facing the women’s movement or its inability to push for its demands and readjust them in the new political environment. Much of this discourse is emanating from a few activists who are better known and respected internationally and in my view intent on convincing an international audience of their own centrality in the viability of the Iranian women’s movement. The reality is that if the women’s movement in Iran and the Campaign are facing a crisis, it is not any different than, nor is it apart from the crisis faced by the Iranian society at large. How the women’s movement ends up positioning itself with respect to the larger movement for democracy in Iran and future political and social developments is a question that we have all grappled with over the past year and will continue to struggle with in the years to come. But this is a task that is best suited for activists on the ground to decide on. Certainly the women’s movement’s positioning will become clear with the passing of time. It is indeed true that since the disputed presidential elections in June 2009, the accomplishments of the women’s movement and the Campaign have not been reflected fully in the media—even our own medias and websites— but this lack of reporting should not be viewed as a sign of dormancy. What has been reported, however, represents only a small portion of what women’s rights activists have been engaged in over the last year or so. Still, the fact that Campaign activists have reorganized and changed strategies to focus more on awareness raising, training over 400 activists in the past year alone (when much of Iranian society was embroiled in the post election crackdown), conducting street outreach on special occasions and continuing with their signature collection, drives the message home that both the Iranian Women’s movement and the Campaign are alive.

Re-strategizing for an even more difficult and challenging political climate, but maintaining a focus on women’s rights and awareness-raising is only a testament to the innovation of the Campaign and the resolve of its activists. So on the fourth anniversary of the Campaign, despite not having reached its goals of signature collection or sweeping changes in the law, the Campaign continues along its path with lesser known and younger activists at the helm, who through four years of activism and experience have learned that a movement can stay alive only if it is decentralized and its structure participatory. In fact, these developments and accomplishments do much to demonstrate that the Campaign and the Iranian women’s movement are an active part of Iranian society creating and promoting change—often with ebbs and flows, but nevertheless moving forward steadfastly.

Take a look at the English Face-to-Face Section of the site of Change for Equality

Read the Face-to-Face accounts written by activists and published for the first time in celebration of four years of our presence on the streets and among the public.

People Still Have Hope for the Future

Sometimes People Need to Feel the Pain

These Laws Aren’t Discriminatory, they’re Supports!!

Collecting Signatures on the Bus

The Never Ending Sorrow of Women and the Cherished Wealth of the Campaign

Note: Some of the activities that Campaign activists have engaged in over the last few months include:

1. Public outreach and education on the streets for March 8 International Women’s Day;

2. Public outreach and education on the streets for June 12 the anniversary of the day of solidarity of Iranian women;

3. Producing and publishing a web-based collection of essays examining the relationship of the green movement with the Campaign and the women’s movement at large for June 12. It should be noted that websites are still managed from inside Iran, with an internet speed that is so slow it is often mind-numbing; and

4. Publishing a series of interviews on the Campaign in observance of its anniversary, including a report on the training of over 400 individuals and a report of a survey about the impact of the Campaign conducted with approximately 1200 citizens across Iran.

| Recently by Sussan Tahmasebi | Comments | Date |

|---|---|---|

| Turning 43 in Prison | 2 | May 25, 2011 |

| The Birth of Hope | 4 | Apr 10, 2011 |

RECENT COMMENTS

IRANIANS OF THE DAY

| Person | About | Day |

|---|---|---|

| نسرین ستوده: زندانی روز | Dec 04 | |

| Saeed Malekpour: Prisoner of the day | Lawyer says death sentence suspended | Dec 03 |

| Majid Tavakoli: Prisoner of the day | Iterview with mother | Dec 02 |

| احسان نراقی: جامعه شناس و نویسنده ۱۳۰۵-۱۳۹۱ | Dec 02 | |

| Nasrin Sotoudeh: Prisoner of the day | 46 days on hunger strike | Dec 01 |

| Nasrin Sotoudeh: Graffiti | In Barcelona | Nov 30 |

| گوهر عشقی: مادر ستار بهشتی | Nov 30 | |

| Abdollah Momeni: Prisoner of the day | Activist denied leave and family visits for 1.5 years | Nov 30 |

| محمد کلالی: یکی از حمله کنندگان به سفارت ایران در برلین | Nov 29 | |

| Habibollah Golparipour: Prisoner of the day | Kurdish Activist on Death Row | Nov 28 |

Heroic

by Jahanshah Javid on Wed Sep 01, 2010 03:54 AM PDTWhat this organization has done to promote equality in extreme conditions is nothing short of heroic. The way organizers have conducted themselves should be a model for civil action. They have braved constant threats, physical abuse, loss of employment and liberty only for objecting to laws and policies which denigrate women.

I feel bad that publishing this article and expressing words of support and appreciation can cost you harsher treatment. But I assume that you are in this struggle knowing full well that change does not come easy or without cost.

Thank you for your vision, courage and perseverance.

I think the main focus should be to support activists in prisons

by Anonymouse on Tue Aug 31, 2010 08:53 AM PDTI agree that the women's movement is a part of the larger democracy movement and they're both in crisis. As you say some of the well known activists have migrated and again this holds true for the remainder of the movement.

Perhaps it is regime's strategy to allow activists to get out on bail so that they're given a chance to migrate. Although I don't know to make this assertion but one of the things they did years ago when they arrested activists was to confiscate their passports and ban them from leaving the country.

The movement that started last year doesn't suddenly vanish. It is still there and by all accounts gaining more support albeit underground. So I'd say support for those in custody and bringing their plight and keeping their names alive should be an important focus for the movement. I certainly agree that it is up to those on the ground to decide which way to steer the movement and our job to support them.

Good article and more power to the new generation of activists!

Everything is sacred