به زبان فارسی

PICTORY

LATEST MUSIC

SEARCH

The Maharajas’ Jaipur

by Keyvan Tabari

25-Jul-2010

abstract: Tourists are beckoned by the colors of Rajasthan. Splashed over gelatin or equivalents, these colors draw the magic of their aesthetics from contrasts. The women of Rajasthan defy the drab monotone of a semi arid environment by riots of red, green, blue, and orange in their garments. Colorful spices and dried fruit in the markets are the answer to the dearth of fresh, tasty produce and fruit. The wildly extravagant Maharajahs painted their whole capital city of Jaipur lipstick pink to impress their foreign guests. The colorful trash generated by their impoverished former subjects mock this folly. Just the same, the fabled palaces and glamorous life style of the ruling Rajputs resulted from a history of an equal measure of daring by a proud warrior clan and its obedience to the more powerful. The contemporary life in Jaipur plays against that background. This is a glimpse into all that drama.

***

The Road

The main highway from Delhi south leads to mediaeval times. Just outside of town we were sharing this toll road with camels and bullocks used as common means of transportation. “Camel and bullock driven carts are exempt from the toll taxes,” our tour guide said matter of factly. Just beyond the ditch on the side of the highway we could see red-faced monkeys jumping off tree branches. “This type monkeys are aggressive and could be dangerous,” the guide said. Some were perilously close to the road. We also spotted antelopes “with the face of the cow and the body of the horse,” who were “the favorite food of tigers,” as our guide said.

We were now down from the bus on the road, hurrying to have a better look at a special sight along the other side. A man was sweeping the ground as he was moving up in the opposite direction on the road. A woman in a saffron-colored robe walked behind of him. Every few steps she would fall down and crawl a few feet on the road. A rickshaw carrying their belongings was accompanying them. “They are on pilgrimage to the shrine of Hanuman, the Monkey God, hundreds of miles away,” our guide explained. “This is to show their gratitude for having been granted the wishes in their prayers.” The guide then added, “in veneration of the Monkey God, Tuesday is a holy day. It is dedicated to Hanuman, just as there is a holy day for the worship of cows.” Cows were loose everywhere around us. “You can’t tie them; they are treated with respect.” The guide said, “A driver will be more easily forgiven for hitting a man than a cow.”

The couple on pilgrimage had just passed a store, where a sadhu with a white turban was sitting outside. He was “a holy man, a worshiper of god Shiva, who has renounced this world,” our guide described him. “Some sadhuses are very learned.” On our side of the road, not far from here was the shrine to Vishnu built by the industrialist Birla family. If Monkey God spoke to the reverence for animals in Hinduism, Vishnu was the apotheoses of man. Birla’s Vishnu was a meta-human size sculpture modeled after man. There were two such anthropomorphic divine sculptures. One was Vishnu’s 7th reincarnation as Rama, with quiver and arrows, standing alongside his consort Sita. The other was Vishnu’s 8th reincarnation as Krishna, a cowherd with a flute. The sacred text Ramayana is about Rama, and Mahabharata is about Krishna. “The 9th reincarnation of Vishnu is Buddha; his earlier reincarnations are not in the literature,” our guide said.

The guide continued, “Vishnu is the Protector in our trinity of Hindu divines, the other two being Brahma, the Generator, and Shiva, the Destroyer who thus makes possible the birth of the new.” Is Sita also a God, a fellow traveler asked the guide? “I don’t know what to call her, a God, a Mrs. God?” the guide said. “In fact it is not certain if there is any God like the Christian God in Hinduism. But Indians are very religious. They hardly pass a holy place without offering prayers, no matter to which God.” Then he showed us the Shiva Lingam, “for male, vertical, and for female, like a saucer,” saying this abstract presentation perhaps served better to express the Hindu idea of divinity.

We drove a long stretch of dusty road in the shadow of the Vindhya mountain range of Rajasthan. The severe monotone of the landscape was only occasionally interrupted by the vibrant colors of dresses on women from the nearby villages. In the roadside open-door sheds of dhabas cafes the truckers ate, sitting on wooden platform beds. They drank Kingfisher beer, which has made India’s “liquor king,” Dr. William Mallya, a billionaire, ignoring a sign across the road that advertised “English Wine,” which meant such things as gin, rum, and wine.

We were taken to the village of Chomu for lunch. On the sidewalk of a street here I observed the rare signs of another religion. A small group of men were praying on the sidewalk in front of a modest white building that served as their Mosque. They faced Kaaba, the cube-shaped building in Mecca, which according to Islamic beliefs was rebuilt by Prophet Abraham on the foundations of the first building on earth, built by Adam. This was perhaps as close as the Muslims came to the notion of “lingam,” a physical “sign” of God.

Rajputs’ Palace Hotel

In Chomu the highway shrank to a narrow paved strip in the middle of a wider dirt road. The cluster of shacks we had seen in a few places on the road became bigger and combined with a few shapeless low buildings to give Chomu the appearance of a market town for farmers. The goods were mostly fruit and produce displayed on carts pulled by donkeys. The service sector was mostly comprised of motorcycle and bicycle repair shops. Chomu also boasted a hotel. Its narrow three-story building was a sharp contrast to the grand Palace Hotel reserved mostly for foreign tourists. The staff welcomed us as guests by the customary planting of a red dot with a rice grain in its middle on our forehead. The entrance gate displayed a carving of Ganesh (the elephant-trunk God of good luck and prosperity), which is customary so as to wish an auspicious beginning for any occasion. Our one wish appeared about to be fulfilled soon, after a long drive in the hot sun, as we glanced at the main courtyard where a waiter was holding a tray of cold drinks for us. A sumptuous lunch was then served in a magnificent room with balconies and painted walls, presided over by a portrait of a Rajasthani Maharaja.

The Palace Hotel complex included several well-groomed private gardens, and rooms which had elaborately decorated walls and mirror-work ceilings. “At one time there were more than 500 princely states in India,” our tour guide began in his narrative about the Chomu Palace Hotel. “Only Ashoka the Great in 3rd century and the Mughal Emperor Akbar in the 16th century were able to establish a united India. After independence the princes were asked to join the Union in return for a stipend from the government. Prime Minister Indira Gandhi abolished that stipend and so the princes had to turn their palaces, like this one in Chomu, into ‘heritage’ hotels.”

The fact that in our guide’s opinion only a Buddhist (Ashoka) and a Muslim (Akbar) were able to unite India in the long stretches of its history was noteworthy. The guide was an ardent Hindu of the Brahmin caste; and this was central India, the heartland of the recently resurgent Hindu pride. The Chomu Palace indeed reflected parts of India’s history. It was originally built as a fort (hence called Chomugdth) in the 18th century by the local Rajput rulers and turned into a palace in the late 19th century by their eventual successors. These Rajputs (sons of Raja) descended from the kings of the Chauhan Dynasty of the Hindu Kachwahas, the dominant clan in this part of India. The Chauhans’ rule began in the late 7th century. Control of this area changed hands over time among the Muslim Delhi Sultanates, their Mughals successors, and the Hindu Marathas until the British seized it in the 19th century. The British Raj’s rule here was indirect, through their overseeing Residency Agency; their local satraps were the Rajas (from the Sanskrit rajan, a cognate of the Latin regis, meaning king) who were mostly related to the Chauhans.

There were 19 such Rajas in this area just before India’s Independence. They were of various ranks, depending primarily on the extent of their services to the British, which was indicated by the number of gun salutes they could receive. Valuing status, even the lowliest Rajas preferred the title of Maharaja (Great King). In 1944 eight of these Maharajas formed the Greater Rajasthan Union; and all 19 eventually joined the Independent Indian Union, creating its largest State, Rajasthan (the Abode of the Rajas) in 1956, with Jaipur as its capital.

City View

In this capital city our arrival was heralded by a ragtag “drum and bugle corps,” accompanied by a man dressed as a wooden horse. The drum was a version of the Persian dohol, introduced to India in the 15th century, and the bugle resembled another old Persian instrument, the sheypoor of the same era. Together with the musicians’ costumes, their purpose was to take the tourists back to when the Maharajas ruled.

There was a different kind of music coming from the park across the street where two weddings were taking place. We climbed to the roof of the hotel to take a better look. We saw a groom on a white horse in the middle of several wedding attendants and a few musicians. On the other side of the roof the view was that of a sprawling city, which filled up the valley almost all the way to the hills; the smog that the sun burned red covered the spaces that were left empty.

Jaipur likes to be called the Pink City. This is because Maharaja Sawai Ram Singh II ordered the whole city, as it existed in 1853, painted pink on the occasion of a visit by Prince Albert of England. The monsoon rains on the Maharaja’s legacy every year. It is painted over again every five years, except for the Maharajas’ palaces, which are painted every three years. The new paint on the buildings is salutary because it distracts from the piles of trash that cover too much of the grounds in the city.

Jaipur Design

Jaipur also makes claim to the title of the oldest surviving planned urban center in northern India. Maharaja Sawai Jai (Victory) Singh II who named the new city after himself, employed a scholar to design it as conceived in Shipla Shastra, the ancient Hindu architectural treatise. The grid consisted of seven blocks of white buildings separated by tree-lined wide boulevards. It was a walled city with seven gates. Arched shop-fronts added the Mughal architectural influence. That was in 1727. Now those elements can be uncovered only with difficulty in the maze of extraneous additions such as the tangled webs of electricity wires, not to mention the crumbling walls, the street traffic of vehicles and animals of diverse variety (camels, cows, goats, and pigs), and crowds on the pock-marked pavements.

One addition, in 1799 by Maharaja Sawai Pratap Singh, however, has become the landmark of Jaipur. It is Hawa Mahal, a five-story building, only one-room deep, in the center of town where the Maharajas’ women, “languishing in purdah” (according to a local guidebook, Majestic Jaipur, p 16) would come from their sequestered quarters for protected viewing. It was a place for “taking fresh air (hawa in Persian)” as its name implies. The royal women, unseen, could view the everyday life and processions of the city in the streets below through the arabesque of the building’s 956 small windows. One thing we know they saw was another such viewing structure right across the street. On a smaller scale, this one was for the commoner women of the town. Today the view from windows on both sides was of tourists looking up and the peddlers they attracted, including the emblematic fake exoticism, which is the snake charmer. These cobras were defanged and they were deaf. They did not dance to the music; they moved as they felt threatened “by the movement of the bamboo sticks at the end of the flute,” our guide explained. A few steps away was a milk market. Skeptical Jaipur buyers first dipped their hands into the tin containers of milk to make sure that the sellers had not “diluted it with too much water.”

Amber Fort

Before Jaipur, rulers of this area lived in Amber Fort up on the hills a few miles away. They were from the Kachwahas, a Kshatriya caste clan claiming lineage from the Sun Dynasty (Surya), who came here in the 11th century. When the third Mughal Shahanshah Akbar-e Azam (Persian for Emperor Akbar the Great), expanded his empire (1556-1605) south from Delhi, these Kachwaha Rajputs formed an alliance with him to safeguard their territory. This was symbolized by Akbar’s marriage to the daughter of Raja Bharmal of Amber in 1562. Henceforth called by her Islamic name Mariam-uz-Zamani (Persian for Mary of this Era), she was twenty-year-old Akbar’s first Rajput wife. With the help of his new father-in-law Akbar then used matrimonial diplomacy to help bring under his control other Rajput rulers in central India. Rajput warriors served the Mughal Empire for the next 130 years until the death of Aurangzeb, the last of the “major” Mughal kings. Aurangzeb bestowed the title of Sawai on Jaipur’s Maharaja Jai Singh II (1688-1743). It meant one and a quarter times superior to other men. Jai Singh II’s successors have since entitled themselves Maharaja Sawai. They also continued the reception of many elements of the Persionate culture of the Mughals, as reflected in the many Persian names which I noticed in their remaining institutions in Jaipur.

Mariam-uz-Zamani became one of Akbar’s three main queens, but more important, the mother of his son and successor Jahangir. This connection to the Mughal Emperors rewarded the Amber Rajas. Man Sing I who was Bharmal’s grandson and Mariam’s nephew rose to be one of Akbar’s principal generals, as a Mansabdar (Persian for Titled Commander) of 7,000 cavalry, and one of the Navartnas (Sanskrit for Nine Jewels), or extraordinary counselors, in the Emperor’s court. He was given the Mughal title of chief, Mirza (From amirzadeh, Persian for the son of Amir), as Akbar came to call him farzand (Persian for son).

It was Mirza Raja Man Singh I who in 1569 began the construction of the Amber Fort, which I was going to see now. Our guide’s name was Mr. Singh (Sanskrit for lion, denoting warrior caste Kshatriya ties), which he said “means a Rajput warrior.”

The walls of the old Fort looked impressive as they snaked around the surrounding hills. I sat in a Jeep to drive up the narrow climbing road, through the streets of the old settlement. My driver was Shoja (Persian for brave) Khan who said he was born and raised in that village; he let me hold the jeep’s wheel while we talked. We arrived in the central courtyard of the Fort as braver tourists were disembarking from their elephants. Our tour guide explained, “We have been using jeeps after an elephant killed his mahout (rider) recently.” He took us to see how the mahouts were tying the new baby elephants to chains so that they “get into a sate of mind not to run away.”

The courtyard, Jaleb Chowk, which was once the Fort’s parade grounds for the warriors, today served as a stage for a colorful carnival of tourists that would have pleased Federico Fellini. The original part of the Fort, built by Mirza Raja Man Sing I was in the back, behind the part built by his descendant Mirza Raja Jai Singh I who became the Raja of Amber in 1614. The old parts were far more Spartan than the palace of Jai Singh’s creation, a testimony to how dramatically the Rajas fortunes had improved in the seventy years of protection and patronage by the Mughals. The new complex was almost a complete version of the Mughals’ Palace Fort in Agra (which I also saw that week), but on a far more modest scale. Diwan-i-Aam (Persian for Hall of Public Audience) was the prominent building in the Jaleb Chowk, with white and pink sandstone columns giving it a stately appearance. Here, the Raja held darbar (Persian for court) with his officials and received petitions from his subjects. The toshakhana (from Persian tusheh-khaneh, meaning “provisions house”), housing government offices that administered the Amber state was next door under a series of colonnaded arches.

As I saw in a picture of a later period, the Rajas’ darbar was only for men. The women in Amber Fort could try to see the proceedings in the Public Audience Hall only through the small openings in the outer wall of the private quarters which functioned the same way as in the Hawa Mahal. There was a special residential section, called Zenani (Persian for Ladies) Deorhi (Apartments), for the Raja’s mother, consorts, and their many “attendants”. Man Singh’s Fort had 12 suites for his 12 wives. Thus once a bustling place, this area now looked drab. On the day of our visit the only attendant was a woman from the lowest caste Shudra who stopped sweeping to beg us for money.

The Raja himself had more opulent accommodations in the Fort. We entered through the ornate Ganesh Pol (Gate) which had a small painting of Ganesh on the top. Here was the Diwan-i- Khas (Persian for Hall of Private Audience) built by Raja Jai Singh I, which because of the tiny mirrors on its ceiling and walls is also called Sheesh Mahal (Persian for Hall of Mirrors). In this Hall the Raja received his special guests, including dancing girls who entertained, holding candles which made especially pleasing reflections off the mirrors. Outside, the marble walls were covered with masterful drawings of flowers. Facing the Hall was a sunken garden in the Mughal style of charbagh (Persian for four-sided garden). On the other side of the garden was Sukh Niwas (Pleasure Palace). Some remains of its ornate walls were still standing, but the water fountain that once ran was now dry. The niches with carvings of musical instruments marked it as the music room.

The vast pool that once served Amber was completely empty as there had been too little rain lately. That is a fate that seemed to await the much larger but half-empty Man Sagar Lake down the road, which the Maharajas once used for duck-shooting. Their lodge Jal Mahal (Water Palace) sits there in disrepair with only an illusion of distant romance retained in the elegant symmetry of its architecture.

City Museum

The Maharajas’ City Palace in Jaipur was a complex of several contemporary buildings, all freshly-painted pink, and interconnected by courtyards. It covered one-seventh of the original walled city. It now houses not the Maharajas but a Museum of artifacts of their past lives: arms, paintings, manuscripts, carpets, and textiles. The pieces that most attract the visitors’ attention are two bowls in the Diwan-i- Khas which are said to be the biggest objects made of silver. These gangajlis, each with a capacity of 9,000 liters, were made for Maharaja Sawai Madho Singh II’s journey to England in 1902. They were filled with water from the Ganges River and loaded on the Maharaja’s ship for his use in daily purification rituals. The picture of this corpulent Maharaja as well as that of the spectacled Maharaja Sawai Ram Singh II, who painted the old city pink, are among those hung on the walls of the Palace’s main darbar (Audience Hall).

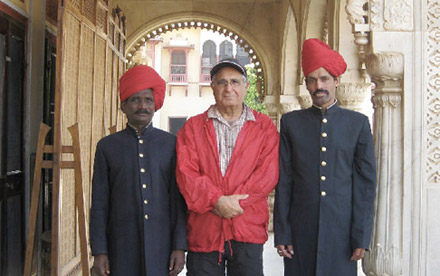

The ceremonial Retainers (Guards) at the Palace, with their white pants, blue long coat, and red turban invited me to have my picture taken with them. Then they asked for a tip. Unlike Amber Fort, the City Palace had many Indian visitors. Our guide Mr. Singh was not pleased to see two women who were in veil. This odhni (veil) “is not compelled by our religion, whereas Islam compels it.” As he explained it, “Hindu women began to put on the veil to protect themselves against the lust of Muslim invaders.” The veil worn by the Muslim women I saw in Jaipur was different and, in fact, covered less than the Hindu odhni.

Jantar Mantar

Another sight in Jaipur which was popular with domestic tourists was Jantar Mantar (Calculation Instrument), an astrological and astronomical observatory built by Maharaja Sawai Jai Singh II in 1728. That Maharaja was “committed to the ambitious task of understanding the universe.” He “dispatched scholars to the intellectual centers of Europe,” Britain, Portugal, and Greece, as well as to “Arabia” to bring back “the latest treatises on the configuration of the planets” (Majestic Jaipur, p 18). He built five observatories in various Indian cities, beginning with Delhi. The one in Jaipur was the biggest. The Maharaja himself studied the imported books and used Jantar Mantar for observations.

The Jaipur observatory was renovated in 1901 and again a few years ago. Of especial interest today was “a sundial that can give the time to an accuracy of 2 seconds”. It looked like an unusual modernist sculpture with stairs going toward celestial entities. A sign described another instrument nearby as the “Stereographic projection of heaven on plane of equator. For observing altitudes and thence finding time and all the positiens (sic) of the heavenly bodies.” Next to it was a structure with small chambers for all months of the Zodiac, each symbolized by a descriptive tile [84]. For Pisces, the tile showed a fish. In the chamber for Gemini, the tile depicted duality by a man and a woman who was playing ektar (Persian for one-string) an instrument normally used for sacred music.

Rambagh

We fought our way through the jumble of cars and cows outside Jantar Mantar to the immaculately maintained green gardens of Rambagh Palace Hotel. Women gardeners in green uniform were watering the lawns; a man in white uniform and red turban strolled around waiving a flag to shoo away birds. Named after the oldest Mughal garden (Babur’s in Agra), this Rambagh (from Persian Aram bagh, meaning garden for rest) had been the residence of the Maharaja of Jaipur from 1925 to 1957. If Jantar Mantar was about “technology transfer” from abroad, this Palace was about “glamour transfer”. Its famous Polo Bar was a good example. We sat under the framed pictures of the likes of Jackie Kennedy (in 1962) and Prince Charles and his wife Diana. They were guests of the dashing Jaipur royal polo players. These royals had changed the name of the ancient game from the original Persian chogan (although the Jaipur Chogan Stadium is still called by that name), and substituted horses for elephants which were used in the old Jaipur style of polo.

The Jaipur Maharajas had undertaken a more important political realignment starting in 1803. With the Mughals having become enfeebled, the Maharajas now looked to the British for help against their local Hindu adversaries, the Marathas. They became “devoted to the British royal family until the end.” They stayed loyal during the 1875 Mutiny, India’s First War of Independence against the British, and for that the Maharajas were awarded with knighthood.

Pictures of the gatherings of several princes of India who were the contemporaries of the last Jaipur Maharaja hung on the walls of the corridors leading to the Rambagh Palace Hotel’s Suvarna Mahal. This restaurant boasted of “exceptionally grand ambience; liveried waiters, gold plated tableware, exquisite china and crystal, grand high ceiling, crystal chandeliers and alabaster lamps, original Florentine ceiling paintings and mirrors.” It also claimed that its “culinary masters have meticulously researched the cuisines of the Royal houses of India, … Jaipur, Mewar, Awadh, Hyderabad, Vijayanagar, Kashmir, Patiala” in preparation of the menu that was now put before us.

The world of the mid 20th century took note of the Jaipur Maharajahs’ glamour when Gayatri Devi was included in the Vogue magazine’s Ten Most Beautiful Women list. An avid equestrienne, she was the Maharani, from 1939 to 1970, the third wife of Man Singh II, the Maharaja Sawai of Jaipur. A son from another wife became Man Singh II’s heir. Bhawani Singh was the first male born to a ruling Jaipur Maharaja for two generations. The occasion, in 1931, called for so many corks of Champaign bottles being popped that the new born was, forever, nicknamed Bubbles, as his nanny first called him.

The age of Bubbles and the Maharani came to an end with Independent India. Jaipur joined some neighboring former princely autocracies to form the State of Rajasthan. The Jaipur Maharaja remained as the ceremonial head of this State until 1956, when that post was eliminated, but he lost his right to tax. The Maharaja died in 1970, on the polo field. Even before that, the Maharani decided to enter politics on her own. She was elected as a deputy to the new Indian parliament by an overwhelming margin, because “she was idolized by the lower-caste Indian,” as The New York Times (July 30, 2009) reported. She served from 1962 to 1975 as a Deputy, opposed to the socialist policies of the Congress Party. In 1975 Prime Minister Gandhi, declaring a state of emergency due to “internal chaos,” had the Maharani arrested, among other political opponents. She was charged with violation of tax laws related to “undeclared caches of gold and jewelry ... found buried on the family property in Jaipur.” As a result the Maharani had to spend five months in prison, after which she retired to a quieter life in Jaipur and abroad until she died in 2009.

Bubbles is still alive. His residence in Jaipur is the seven-story Chandra (Moon) Mahal, which we could see from the old City Palace. He failed in his own run for the Parliament, but he made a name for himself in the Indian-Pakistan war. For serving “with gallantry in the armed forces in the true tradition of the Kachwahas” he rose to the rank of Brigadier before retiring in 1974. Like his father who was the first prince hotelier in India, Bubbles now runs many of the former Jaipur palaces, including the Rambagh, as hotels.

The new family business has created a rift in the former royal family of Jaipur. Bubbles, who does not have a son, in 2002 named the five-year old son of his daughter as his heir. Bubbles’ two brothers sued claiming that their father’s wealth should be shared based on his Will. The Maharani also joined to protest the decision in a “Dear Bubbles” letter. At the time, Indian reporters for The Telegraph, London, (December 30, 2002), estimated the “flamboyant” Bubbles’ wealth to be worth one billion dollars. The Times estimated that the Maharani “had almost unimaginable wealth,” while she and her husband “ruled over a fief of some two million peasants.” A half million of these lined the streets when that last Maharaja’s body was taken for cremation. Coincidentally, nearly half of Rajasthan’s population was still illiterate, according to our guide.

Shops

The glossy guide book I bought in Jaipur, Majestic Jaipur, traces the increasing fortune of its ten Maharajahs to their “active encouragement of merchants and tradesmen (p 20).” Perhaps of equal importance was the impact of the Mughal Emperor Akbar’s decision in 1562 to abolish the jizya, a tax which all non-Muslims were required to pay.

We were taken to see a fabric block printing center “to learn more about the textiles that are so representative of this area,” as our tour guide said. Next was a wool carpet store, because “Rajasthan makes the best wool carpet”. The sales clerk put a lighter’s flame to the fuzz of the carpet to demonstrate that it was so tightly woven that it would not catch fire. I was more interested in the working conditions of two women spinning the yarns; they were sitting on the ground in the store’s backyard.

When we climbed our bus we were swarmed with peddlers hoping to sell their cheap souvenirs. Our guide stopped them at the door. He then chose some of their goods to present to those interested among us. This was the guide’s standard practice for controlling the usual rush of street vendors to tourist vehicles. He was also compassionate: “I do this because if we don’t buy from them, they will have no choice but to become beggars.”

On the way to visit a jewelry store “to learn about the gems that India is so justly famous for,” our guide said that “Jaipur was the world’s largest wholesale market in Jewelry. There are 300,000 people working in the jewelry industry. Ten percent of them are actually cutting and preparing and the rest are traders.” The Jaipur’s jewelry craftsmen are especially famous for their kundan (possibly from Persian kandan, meaning carving) and minakari (Persian for enameling).

I saw some of the jewelry “traders” in Jaipur’s Johari (Persian jawaheri, meaning Jewelry) Bazaar. They stood outside their shops asking passerby “Hello, what do you want?.” They, the shop-owners, and the sales clerk were all men. Almost all the shoppers were women; almost all the merchandise they were looking for were decorative accessories. True to its meaning, the bazaar was chaotic. At its entrance, right on the street, a woman ran a laundry business, washing the clothes before your eyes.

Transition

“Shopping malls are new,” our tour guide said, “only from the last five years; and only in some places.” I saw examples in Delhi and Agra. They had only a few shoppers; their quiet made you miss the excitement of the bazaar. This was also true of the new temples. The elaborate ornamentation that I could glance on the old Hindu temple of the village in Amber was forfeited for the cold white marble of Jaipur’s new Shri Lakshmi Narayan temple. Not the “merest speck of dust” was to be seen in the huge 1970s air-conditioned building and its plaza. It exuded “a faintly Orwellian chill,” noted the Majestic Jaipur (p 23). Its stern protective guards’ crowd control measures at one point irked our tour guide. I had to pull him away from confrontation.

Like the shrine to Vishnu we had seen some miles outside of Delhi, the Narayan temple in Jaipur was a charitable contribution by the industrialist Birlas. As such it was a monument to the capitalism that has replaced the feudal rule of the Maharajas who have ceased to build palaces. The temple’s green gardens pulled in the average extended families of Jaipur. We were invited by a more prosperous extended family to their home. They lined up to greet us at the entrance to their spacious garden. The owners’ son and daughter-in-law (and their children) lived with them, although both had good jobs as proprietors of a private school.

The father showed us his sprawling house of several rooms full of furniture worthy of a respected burgher. His wife’s traditional status was affirmed in the pictures of their wedding on the walls: she was sitting on a chair and he stood regally behind her. Two elegant rifles also on the wall connected us to Jaipur’s Rajput past. A mounted stuffed head of a tiger in between them, however, signified that they were used more in hunting. Our host, indeed, had spent his last working years as a warden of a game preserve. So he symbolized still another step in the transition of Jaipur’s society.

This family, as it turned out, was even more fully such a bridge between the past and the future.

The owners’ daughter also lived with them. She joined us later for dinner, having just returned from work. She was the only one in the family who wore western clothes. She was a professional, she said, “a clothes designer.” This was around the time India’s Prime Minister was visiting the U.S. and the American President had just given a State Dinner in his honor. Indian papers proudly featured the story of the American First Lady wearing a dress designed by an Indian to that dinner. When I brought that subject up, my young hostess said that she knew the designer. This hostess was a rare divorced woman in India. “The rate of divorce in India is only 15%,” our tour guide had said. My hostess was attractive, but tonight she looked tired, maybe even sad, maybe even bored with this business of hosting strangers that her jovial retired father seemed to enjoy.

| Recently by Keyvan Tabari | Comments | Date |

|---|---|---|

| On the Map | 3 | Jul 31, 2012 |

| Puerto Vallarta | - | Jul 31, 2012 |

| Anchoring in the soil | 1 | Jul 01, 2012 |

RECENT COMMENTS

IRANIANS OF THE DAY

| Person | About | Day |

|---|---|---|

| نسرین ستوده: زندانی روز | Dec 04 | |

| Saeed Malekpour: Prisoner of the day | Lawyer says death sentence suspended | Dec 03 |

| Majid Tavakoli: Prisoner of the day | Iterview with mother | Dec 02 |

| احسان نراقی: جامعه شناس و نویسنده ۱۳۰۵-۱۳۹۱ | Dec 02 | |

| Nasrin Sotoudeh: Prisoner of the day | 46 days on hunger strike | Dec 01 |

| Nasrin Sotoudeh: Graffiti | In Barcelona | Nov 30 |

| گوهر عشقی: مادر ستار بهشتی | Nov 30 | |

| Abdollah Momeni: Prisoner of the day | Activist denied leave and family visits for 1.5 years | Nov 30 |

| محمد کلالی: یکی از حمله کنندگان به سفارت ایران در برلین | Nov 29 | |

| Habibollah Golparipour: Prisoner of the day | Kurdish Activist on Death Row | Nov 28 |