به زبان فارسی

PICTORY

LATEST MUSIC

SEARCH

From Iran to Hollwood: Book Review

by bparhami

15-Jul-2012

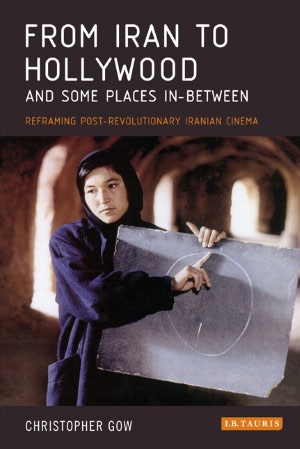

Gow, Christopher, From Iran to Hollywood and Some Places in-Between: Reframing Post-Revolutionary Iranian Cinema, I. B. Tauris, 2011.

Summary: An outsider’s view of domestic and émigré Iranian cinemas, with the thesis that the “new” post-revolutionary Iranian cinema is in fact a continuation of rich filmmaking traditions that were merely interrupted by the Islamic Revolution.

Cinema has always been a puzzle in Iran. During the Shah’s regime, it was both an ally and a thorn in the side of the dictator. Movies were made to entertain and distract audiences or to sing the praises of the King of Kings, who was moving Iran toward “the Great Civilization.” There were also films with direct or thinly disguised political messages that would never see the light of day or were screened only after the censors were satisfied through cuts, alternate dialog, or, occasionally, changes in the storyline.

In the first couple of decades after the Islamic revolution, things hardly changed as a matter of principle: we had propaganda films and independent (art) films. The former toed the official line of sanctioned themes and storylines, while the latter experienced a period of dormancy as new rules were being laid out, and then tried to stay afloat through innovative storytelling within the rigid framework on what was and was not allowed. A prime casualty was depiction of women in satisfying and complex roles; children, on the other hand, became major characters in films because they could act and talk rather freely, and lament over their harsh living conditions, without getting the filmmaker into trouble. Childlike dialog or playfulness was acceptable where their adult counterparts might have fallen prey to censors.

It isn’t until pp. 57-59 that we find out what this book is about: “The paradoxes of the new Iranian cinema are many: new yet old; global yet local; modernist yet postmodern; Islamic yet secular. A better understanding of these paradoxes is nevertheless crucial to the more comprehensive panorama of Iranian filmmaking … Iranian filmmakers are very conscious of how they and their country are perceived. They are more than aware of who is watching them, whether the glance is cast from outside or from within their own country.”

The author is distressed by the fact that foreign audiences sometimes act as if the new Iranian Cinema is a product of the Islamic Revolution, thus overlooking the filmmaking traditions and influences that preceded them. “More often than not the Revolution is perceived as a catalyst for, rather than an interruption of, Iranian cinema’s creative renaissance” [p. 3]. The rich pre-revolutionary traditions of Iranian cinema are often overlooked in the West [p. 10]. The progressive image of Iran that has emerged through its cinematic success, and the associated prestige enjoyed by Iranian filmmakers, is in stark contrast to the clichés of bearded men, veiled women, raised fists, and blindfolded hostages that have been paraded endlessly in Western media [p. 41].

The Islamic regime thought, for a while, that it could exploit this new prestige to boost its image abroad, but in the end, decided that cinema was more trouble than help. Recently, regime officials have stepped up their attacks against film artists, actresses in particular, as exemplified by one referring to Leila Hatami’s very modest outfit at the Cannes Film Festival as “lewd” and Mashregh News manufacturing a fake news story about Shohreh Aghdashloo’s supposed drug abuse. It was within this troubling new context, which was of course unknown to the author when he wrote his manuscript, that I began writing this review.

One interesting dilemma of the author was coming up with a precise definition of what constitutes Iranian cinema [p. 64]. The success of Iranian filmmakers has made projects with international financing, and participation by foreign artists, quite common in recent years. Should one count a film directed by an Iranian, but featuring cast and crew from other nationalities, as an Iranian film? What about émigré or exiled artists? Is a film made by Iranians living in Germany still part of Iranian cinema? How does the question of exile vs. diaspora (as analyzed by Hamid Naficy; p. 71) figure in this regard?

Hence, the author’s decision to devote separate chapters to native and émigré Iranian cinemas (Chapters 1-2, comprised of 51 and 66 pages, respectively). He augments these two main chapters with “close ups” on filmmakers Amir Naderi and Sohrab Shahid Saless (Chapters 3-4, 20 and 43 pages). The foregoing chapters are sandwiched between short introductory and concluding chapters (8 and 12 pages). The book ends with notes (12 pp.), bibliography (10 pp.), filmography (3 pp.), and index (7 pp.).

Acknowledging his limitations as a non-Iranian observer of Iranian cinema, the author hopes that his “foreigner” status can help bring a new perspective to an area of study that has been dominated by Iranian academics working in the West, stating parenthetically that many Iranians have found Kiarostami’s films just as challenging and problematic as the author has.

I have written elsewhere (see my review of The Politics of Iranian Cinema, //iranian.com/main/2010/apr/more-credit-t...) that critics are often too kind to Iranian cinema (and to art films, in general): “Iranian filmmakers may be given more credit than they deserve, both inside and outside the country. Audiences in Iran sometimes read nonexistent political messages in ambiguities that may have resulted from censorship or poor cinematic execution. Festival critics and foreign audiences tend to view those same ambiguities as signs of sophistication or depth.”

If a microphone or a flying plane appears in a scene from a movie set in ancient times, it is normally identified as a sign of a low-budget B-movie. In an art film, the same faux pas may be construed as a clever device for mixing fiction and reality. The author is aware of the corrupting influences of film festivals on national cinemas, quoting Bill Nichols [p. 42]: “Films from nations not previously regarded as prominent film-producing countries [such as Iran in 1989] receive praise for their ability to transcend local issues and provincial tastes while simultaneously providing a window onto a different culture.”

The book treats the Islamization of domestic Iranian cinema and what it has meant to various film genres rather superficially. The effects of Islamization on women is discussed in the context of this quote from Hamid Naficy [pp. 47-48]: “It is in the portrayal and treatment of women that the tensions surrounding the Islamization of cinema crystallize … Muslim women must be shown to be chaste … not to be treated like commodities or used to arouse sexual desires … [which] meant that until recently women were often filmed in long-shot, with few close-ups or facial expressions.”

Chapter 2 on Iranian émigré cinema begins with a lengthy discussion of the distinction between exile versus diaspora, with minimal cinematic content. Part of the reasons for a lack of focus on films in this chapter is the author’s difficulty in obtaining copies of films in this category. It is interesting that the author is compelled to discuss in this chapter “The House of Sand and Fog” [p. 120], a film about an Iranian family that has little to do with Iranian cinema. The film is made relevant to the discussion by the fact that it introduced the difficulties of life in exile to mainstream international audiences. These same difficulties were prominent in émigré films immediately after the revolution, when storylines focused on dislocation, anxiety over visas, dealing with racism and hostility toward people of Iranian origins, but they did not attract as much attention.

It is increasingly true that for some filmmakers, freedom of expression and professional fulfillment trump nationality. In an interview with Hamid Naficy, Saless once showed his trepidation over this issue [p. 187]: “I must admit with extreme sadness that I have no nostalgic longing for Iran. When each morning I set foot outside my house … I would feel at home, because I had no difficulties. … I think one’s homeland is not one’s place of birth, but the country that gives one a place to stay, to work, and to make a living.” Yet, even though Saless spent much of his filmmaking career in Germany, there is an unmistakable similarity between his work and that of Kiarostami [p. 187]. Unlike Saless, however, Naderi’s work is assessed as exhibiting “a clean break with his filmmaking past upon moving to the United States” [pp. 145-146].

Having read this book, I agree with the author that his outsider’s views and analyses have enriched the discussion of Iranian cinema. At the end of Chapter 2, two films by directors who returned to Iran after 20-year absences are noted as examples of collaborative efforts between Iranian local and émigré filmmakers: Parviz Kimiavi’s “Iran is My Land” (1999) and Fariborz D. Diaan’s “Iran Is My Home” (2003).

This blending of approaches and styles is viewed as inevitable by the author [p. 199]: “History has proven that very few national cinemas are capable of sustaining indefinitely the interest of foreign audiences. The decline in popularity of the New Iranian Cinema is, therefore, perhaps an inevitability.” Cinema has assumed a transnational nature and it is becoming increasingly more difficult to draw boundaries between what used to be distinctive national cinemas in Europe and elsewhere. Even the lines between art films and Hollywood-style commercial movies are becoming blurred.

| Recently by bparhami | Comments | Date |

|---|---|---|

| Brief book review: Mosaddegh from his own words | - | Nov 05, 2012 |

| Book Review: Forugh Farrokhzad, Poet of Modern Iran | - | Mar 31, 2012 |

| Souvenir of Ancient Norooz | 2 | Mar 18, 2012 |

RECENT COMMENTS

IRANIANS OF THE DAY

| Person | About | Day |

|---|---|---|

| نسرین ستوده: زندانی روز | Dec 04 | |

| Saeed Malekpour: Prisoner of the day | Lawyer says death sentence suspended | Dec 03 |

| Majid Tavakoli: Prisoner of the day | Iterview with mother | Dec 02 |

| احسان نراقی: جامعه شناس و نویسنده ۱۳۰۵-۱۳۹۱ | Dec 02 | |

| Nasrin Sotoudeh: Prisoner of the day | 46 days on hunger strike | Dec 01 |

| Nasrin Sotoudeh: Graffiti | In Barcelona | Nov 30 |

| گوهر عشقی: مادر ستار بهشتی | Nov 30 | |

| Abdollah Momeni: Prisoner of the day | Activist denied leave and family visits for 1.5 years | Nov 30 |

| محمد کلالی: یکی از حمله کنندگان به سفارت ایران در برلین | Nov 29 | |

| Habibollah Golparipour: Prisoner of the day | Kurdish Activist on Death Row | Nov 28 |