به زبان فارسی

PICTORY

LATEST MUSIC

SEARCH

Kabul Days (15)

by Hossein Shahidi

25-May-2012

PARTS: 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33, 34, 35, 36, 37, 38

The Double-Sworded King and the Battle of Maiwand

Monday, 14 April 2003

It finally rained today, briefly but powerfully, and cleared a lot of dust.

The day at the office was taken up with a lot of reading, some writing, a visit by an Afghan friend from the BBC days and a few meetings: one was about our team’s budget over the next year; another was a performance review of a member of the team; and finally there was a meeting with an umbrella UN organisation about information and media relations.

In the afternoon, the Afghan journalist who supervised the coverage of 8 March for us came in with the second version of his report. The first version was full of emotional assertions about Afghan women’s conditions in the past, their efforts now, and the hopes for their future. The new one had a lot more quotes from the women who had participated in the events and was more in line with what we would like to publish.

This led to a discussion about editorial issues, especially the idea of the journalist leaving himself/herself out of the picture and letting the participants in an event to speak for themselves, especially when men are writing about women’s activities. Our friend was still fond of his first version, saying that as the father of four daughters, he had to raise the flag for women’s rights. My suggestion, which he accepted, was that it would be best to leave it to the women themselves to decide if they needed a flag, and who should carry it.

In the evening, BBC news once again gave the title of mercenary to the young Arabs who have gone to Iraq to fight, while they are very unlikely to have done so for money. The American and British soldiers, on the other hand, are volunteer, professional soldiers who are getting paid essentially to kill, an activity they describe as ‘work’.

Another report showed Iraqi police and American soldiers on joint patrols in Baghdad. All that is needed now is joint presidency by Saddam Hussein and Bush – pretty much as in the days when Saddam was Washington’s friend. This will take life in Iraq back to ‘normal’.

Tuesday, 15 April 2003

Today, it rained for several hours, starting at around 10am and finishing by mid afternoon. Unlike early morning when you could still smell moist diesel fumes created by yesterday’s quick downpour, by the end of today’s rain the air was clean and a clear blue sky had appeared from behind the clouds. This was all fine, except that the rain has also washed away quite a lot of blossoms, including a magnificent display on a pear tree in our UN garden. I suppose the sight of all types of fruits on the trees later in the year will make up for today’s loss of beauty.

What’s much more important is that so much rain may help the people of Afghanistan recover some of the losses they have suffered because of several years of draught, on top of all the other difficulties. As I’ve told you before, already there is more electricity around, although its distribution is still far from even and regular. Yesterday, I learned from our guard Ashraf that they are now able to get water from the well in their house, by a rubber bucket, for washing. For drinking water, they still have to go to another well some distance away. Mr Karzai said recently that the unusually heavy rain and snow had done more to help Afghanistan than all the international aid given to the country.

Today, we also had a planning meeting to discuss our 4-year strategy, map out the relevant objectives and activities and work out the means and methods needed to evaluate the success – or failure – of what we do. Like all such meetings, it had slow periods but it did bring many of us together for a full day and helped with greater personal and professional familiarisation.

Since I arrived here nearly two-and-a-half months ago, Agha Sarwar has been serving us tangerines, bananas and apples for dessert – before green tea and biscuits or his fantastic cakes. Over the past couple of weeks, my housemates had been complaining of the never-changing mix of fruits, but Parvin had promised that summer fruits would soon arrive and make all of us happy. Well, last night, we had guavas and cumquats for the first time. This evening, we not only enjoyed the same delicious fruits again - after a delicious vegetarian meal - but could also inhale the sweet aroma of the guavas.

Before you eat your hearts out, let me remind you that I am still in Kabul, where most of the time, for most of the people, life is still full of much less pleasant experiences. Two nights ago, there was a big explosion a long distance away from us, but quite audible here; fortunately no one seems to have been hurt.

Last week, three rockets landed some distance from Kabul, again no one was hurt. Elsewhere in Afghanistan, though, over the past three days more than twenty people have been killed in explosions or faction fights. An unknown number may also have been killed in the south and east of the country where the American forces are sill still fighting. Violence happens so frequently that the top paragraph in our security briefing that summarises the situation often reads like a weather report, with armed attacks and explosions being described pretty much as routine, natural phenomena.

Afghanistan seems to be a model for the minds that are trying to democratise Iraq. So much so that today some Iraqi figures were brought together by the Americans under an air-conditioned tent that from the inside looked like the ‘tent’ under which Afghanistan’s tribal assembly met last year and endorsed the current transitional government. The same ‘tent’ was the site of this year’s 8 March celebrations, as I mentioned in my letters at the time.

The ‘tent’ in Kabul is in fact a very big warehouse-type metal structure equipped with power, air conditioning and a sound system with simultaneous translation facility. It is set up on the grounds of the Kabul Polytechnic, one of the country’s most modern educational establishments, which is now in ruins, of course. The tent was built by the Germans who also hosted the conference in Bonn at which preliminary arrangements for Afghanistan’s post-Taliban governance were made. Although the Afghan ‘tent’ meeting was attended by 3,000 people representing almost all anti-Taliban factions in the country, a year later the country is far from calm and stable.

The tent in Iraq is air-conditioned, erected near a ziggurat built more than four-thousand years ago which is today surrounded by desert. It did not seem to be holding more than a couple of hundred people, some of them caught by the camera enjoying big chunks of kabab. The meeting was boycotted by the biggest Iraqi Shia organisation that is based in Iran.

Chubby Chalabi, the man some Americans want to put up in Iraq, only sent an envoy to the meeting, presumably not wanting to demean himself to the level of people who could at best become ministers. At the same time, there were big protests by Iraqis opposed to American influence at the meeting. With such a start, especially given the symbolism of ancient history, it would be interesting to see what any leadership put together in that tent can do for the cause of democracy.

I am conscious that my account of violence in Afghanistan may worry you. But I thought it would best for you to hear it from me, along with the assurance that we’re all alright, well looked after, and comfortable, and take great care with our activities and movements.

Wednesday, 16 April 2003

Malalai, a beautiful sounding Pashto girl’s name and quite popular in Afghanistan, has been intriguing me for some time. It is the name of a young woman who had a leading role in the 1880 battle of Maywand between Afghan and British forces. That battle has turned Malalai into a symbol of heroism and patriotism. Not only are girls named after her, but also schools and hospitals. Malali is also the name of the most prominent women’s publication in Afghanistan, founded and edited by the indomitable Jamila Mujahid, of whom I have written to you before.

The name intrigues me because of the patriotism it is meant to convey, in the context of an Afghanistan which some of its citizens see as being under foreign influence, if not domination. About a year ago, a young Afghan woman in the south of the country caused a stir, and was likened to Malalai, after she published a poem which said Afghan men were lions being ruled by jackals.

About a week ago, following a discussion on learning while working, I suggested to my team member, Halima, that she could do this by researching Malalai’s life. This would be related to the media, because of Ms Mujahid’s magazine, and would give Halima a chance to study Afghanistan’s history. Having found very little on Malalai on the web, Halima said today that she wanted to get books from Kabul’s central library, especially one about Afghan women which mentions Malalai.

I decided this was a great opportunity for me also to see the library, so we got into an office car and drove to where we thought we had been told the library was. When we got there, there was no trace of such an establishment. The area was packed with people, mostly men, but also some women, most of them in full hijab. There were also many children, some of them sitting on the wall which goes along the Kabul River, eating ice cream. There were also children playing, knee deep, in the muddy water of the river which looked beautiful only because it was flowing.

Before reaching this area, we had passed, once again, by the Television Hill which reminds me of Bush House because it seems wherever you want to go in Kabul you’ve got to pass by it. I had not seen this side of the hill which has a baked-mud wall going up almost to the top of it. Halima explained that the wall had been built by forced labour under a ruler called Zanboorak Shah. Today, the wall looks useless, though at the time it may have served as a Keynesian public works project to keep Zanboorak Shah’s victims busy.

Zanboorak [little bee] is not a name you would associate with someone powerful enough to force people to build a wall up a mountain, and it makes you wonder why anyone would obey him. But obey they did and the wall was built, and it ended up containing the bodies of those who had made Zanboorak Shah angry and had been killed on his orders. He had so many people killed, so the legend goes, that one of his wives got fed up and killed him. This we thought was another example of female heroism, although it is not clear if it’s a model one would like to promote.

A bit further on from the Television Hill, on the bank of Kabul River, we saw a nice, big and elaborate building with a blue dome and minarets. This, I was told, was one of Kabul’s most popular shrines because the prayers and wishes made there would come true. The shrine is the resting place of a saint called Shah-e do-Shamshira, the Double-Sworded King, a Moslem leader who is said to have killed many, many infidels with the two swords in his hands. He continued chopping the enemy down even after his own legs had been chopped off, an impressive achievement which is very difficult to imagine, but has to be accepted on faith.

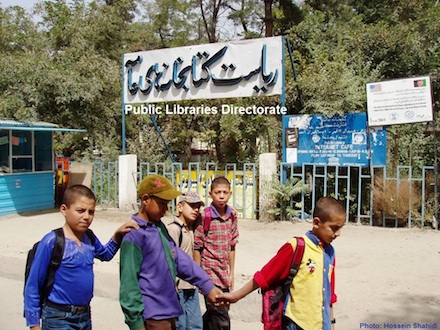

As we reached the shrine, we called our colleagues at the office and – as if by the magic of Shah-e do-Shamshira - they gave us the correct address for the library. It is in fact at the top of the road from our office and I myself had passed by it several times, without noticing the sign. This is one of only two public libraries that are still standing in Kabul. Four others were destroyed and looted, the manager of the reference department told us, during the years of faction fights in the early 1990s. Trying to present the full half of the glass, I said I hoped the looters had at least read the books.

The library is run-down and like all other public and many private establishments in Kabul in need of everything, but it still has the lovely, peaceful feel of a library. The small garden in front of the building really is an oasis of calm, only a few metres away from a very busy, noisy, dusty and gas-oily square. Inside, there is peace and quiet, with people reading and taking notes. The staff, some of whom have been there for decades, are helpful if you gain their confidence.

On our way to the ‘Afghanistanology’ section, we first popped into the children’s section, with lots of titles from Iran. The librarian, who said these were the most popular books, had been in the library for 18 years. In the newspaper department, we came across a charming lady who had just come back from exile in Pakistan, having left Afghanistan after the Taliban takeover. Before that, she had worked in the library for 35 years. She was another of the Afghan women I’ve met with so much knowledge and experience, whose eyes begin to sparkle after they have decided it is safe to speak of their skills, talents and aspirations.

At the Afghansitanology section, on the top floor of the library, we were told that this was a reference, not a lending, department. Books could be borrowed from another department, after the relevant forms had been filled and documents produced. We could, however, consult the book that we wanted and it was brought over: Afghan Women, published in Kabul in1944, by a gentleman called Abdur-Ra’uf Binava (the surname literally meaning pauper). The book’s original cover was glued together with pieces of a newspaper, one of which had a big news story, dated twenty years ago, the time of the Communist Party rule. ‘Under the Party’s leadership,’ the headline said, ‘illiteracy is going to be eliminated.’ Unfortunately, it has not been.

The names of the prominent women mentioned in the book formed the index on the first couple of pages, with Malalai being listed as the entry on page 159. The book did contain pages 158 and 160, but page 159 had been torn out. The helpful librarian found another book published in Pakistan two years ago which did include the missing account from Mr Binava’s work.

Unable to borrow the book, we asked whether we could photocopy the pages on Malalai. The answer was yes, but the two of us and the librarian had to go in search of the photocopier, which turned out to be in another building, in a room with a sign on its locked door which read: Computer Room – Entry Forbidden. The gentleman in charge of the room did turn up after a few minutes and copied the pages for us. Inside the room there were about a dozen big sacks full of books. So the library’s stock is increasing – thank God.

Mr Binava’s account of Malalai contains no factual information about her, but does give a good summary of her image in the minds of the people of Afghanistan. Mr Binava also quotes some of the Pashto poetry that Malalai is said to have recited at the time of the battle, enthusing Afghan men to fight and annihilate the enemy. At the end of the article, there are the names of two other books which mention Malalai, one in Persian and one in English. Those books, in turn, are likely to lead to other sources that need to be consulted. The research on Malalai has just begun.

Thursday, 17 April 2003

Today I came across an article on the web about the Battle of Maiwand with lots of interesting information, including the date of the battle - 27 July 1880 - a very hot day.

At the time, the British, who were concerned about the Russian Empire’s expansion through Afghanistan towards India, controlled much of eastern and southern Afghanistan, having invaded it in 1878. The invasion came after the Emir of Afghanistan received a Russian delegation in Kabul, but his border guards, probably by mistake, turned back a British delegation. The Emir fled and died in Mazar-e-Sharif in the north, which in recent years was the base of the Afghan factions who had been removed from power by the Taliban.

The British stationed troops in Kabul, where the Emir’s son, Sardar Ayub Khan, ruled for a year before being replaced by the British-backed Abdur Rahman Khan. The British also had troops in Qandahar, the biggest city in southern Afghanistan, with a British-backed ruler, Sher Ai Khan. Sardar Ayub Khan became the ruler of Herat, Afghanistan’s second biggest city, in the west of the country near the border with Iran, which was outside British control. Today, Herat is outside the control of Afghanistan’s central government which is backed by the United States.

In the spring of 1880, Sardar Ayub Khan prepared a large force and moved several hundred kilometres southwards to seize Qandahar. The British sent troops out of Qandahar and the battle took place near the village of Maiwand, about eighty kilometres northwest of the city. The British force which was much better resourced and highly trained fired the first shot at 10:45am. By 3pm, the British had lost 1,757 men, plus 175 wounded, 80% of their total fighting force of 2,500 soldiers. The British also had 3,000 service and transport personnel who must have been Indian and whose fate is not recorded in the article.

Sardar Ayub Khan’s force of 8,500 was made up of professional soldiers, tribesmen, ghazis, or volunteers out to fight for the cause of Islam, as well as defectors from the forces of the Qandahar governor, Sher Ali Khan, who had been sent out to support the British. The Afghan force was, therefore, much less disciplined than the British troops. By and large, it also had inferior weapons, including spears and shields. The Afghans lost up to 2,750 men, or just over 30% of their force. After their victory at Maiwand, they laid siege to Qandahar, but were defeated by a British force sent from Kabul.

The battle of Maiwand, says the article, and the loss of 1,700 soldiers in the Zulu wars a year earlier, 1879, were two major military disasters of the Victorian era. ‘The British,’ concludes the article, ‘realised there was no military solution for their political objectives in Afghanistan.’ Shortly after the victory, the British army withdrew from Afghanistan into British India. Afghanistan was reunited and independent again – under Amir Abdur Rahman Khan.

The article includes a brief reference to Malalai, with a different spelling. It speaks of ‘a legendary heroine named Malala who, with a number of other Afghan women, helped the ghazis (Moslem warriors) on the battlefield.’ This happened at a time during the short battle when the Afghan troops had come under pressure. ‘Reciting traditional patriotic ballads, Malala instilled a new spirit of valor and perseverance into the tired tribal warriors.’

A footnote says: ‘One of the couplets says in Pashto: “If you fail to be martyred at Maiwand, by God, my love you will live only a disgraceful life.”’ The footnote adds that ‘Malala’s grave is now a shrine in her native Khik,’ near the battlefield. So, after a relatively extensive look into the battle of Maiwand, a little more information has become available on Malalai. A lot more work is needed to get her out of the footnotes. [For the detailed account, see Colonel Ali A. Jalali, Former Afghan Army, and Mr. Lester W. Grau, Expeditionary Forces: Superior Technology Defeated—The Battle of Maiwand Military Review, May-June 2001.]

***

| Recently by Hossein Shahidi | Comments | Date |

|---|---|---|

| Welcome to Herat | 3 | Oct 13, 2012 |

| Kabul Days (38) | - | Oct 13, 2012 |

| Kabul Days (37) | 1 | Oct 05, 2012 |

RECENT COMMENTS

IRANIANS OF THE DAY

| Person | About | Day |

|---|---|---|

| نسرین ستوده: زندانی روز | Dec 04 | |

| Saeed Malekpour: Prisoner of the day | Lawyer says death sentence suspended | Dec 03 |

| Majid Tavakoli: Prisoner of the day | Iterview with mother | Dec 02 |

| احسان نراقی: جامعه شناس و نویسنده ۱۳۰۵-۱۳۹۱ | Dec 02 | |

| Nasrin Sotoudeh: Prisoner of the day | 46 days on hunger strike | Dec 01 |

| Nasrin Sotoudeh: Graffiti | In Barcelona | Nov 30 |

| گوهر عشقی: مادر ستار بهشتی | Nov 30 | |

| Abdollah Momeni: Prisoner of the day | Activist denied leave and family visits for 1.5 years | Nov 30 |

| محمد کلالی: یکی از حمله کنندگان به سفارت ایران در برلین | Nov 29 | |

| Habibollah Golparipour: Prisoner of the day | Kurdish Activist on Death Row | Nov 28 |