به زبان فارسی

PICTORY

LATEST MUSIC

SEARCH

Witness

by Azarin Sadegh

02-Sep-2008

It’s hard to be a victim. It is harder to be a witness.

Every man in my childhood city -- at some point in their lives -- was one of my father’s students. He had built the first high school of the town, one that allowed only boys. This accomplishment made him walk with pride, showing off his weighty influence.

We lived at the end of a narrow passageway, where, in summertime, the neighborhood boys played with a plastic ball in the dusty road, fought over their turn to ride the postman’s bicycle, and the silence of their absence was the sign of approaching cold.

Mrs. Mostofi, my first grade teacher, lived next door. Every time she made Halva for a religious mourning or celebration, her maid brought a plate to us. “We’re not poor,” my mother used to mumble. If by bad luck Mrs. Mostofi’s path crossed ours, she always gave me old candies and never missed a chance to pinch my plump cheeks with her sharp red nails.

“She’s going to be your best student,” my father would tell her.

“Don’t worry,” Mrs Mostofi would reply, smiling. “She’ll receive my special treatment.”

Living in that small city, on the first day of school I learned that relativity wasn’t just a theorem.

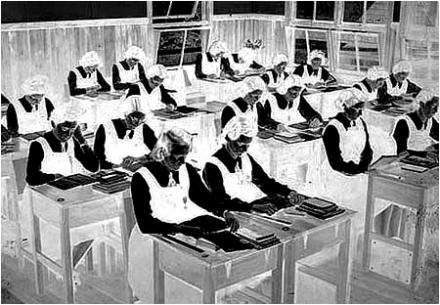

When we lined up and sang the national anthem and praised Shah, and when we prayed to God and cited meaningless Arabic verses, and when we entered class and she welcomed each of us, Mrs. Mostofi showed no sign of recognition.

The earth was turning more slowly than ever as I kept checking the time displayed on the clock hanging over her desk.

In the last hour of the class -- minutes before the bell rang -- she walked slowly between rows, staring at her black notebook, and called -- one by one -- the names of the classmates who never became my friends. I waited impatiently, wondering if she would call my name too. She never did. I was among the few not being chosen.

“This is our daily routine,” she said.

Sitting on an empty bench, I was taken by the sight of the last kid in the line. Leila Taghados was tall and older than the others. I had seen Leila walking home, going back to her village, looking tired and breathless. In the afternoons she worked with her mother as maid in a neighbor’s house. Everyone knew she had already failed first grade multiple times.

The last one in line, the color of Leila’s face and her restlessness and her silent obedience painted an image, a volume in space, a still moment in the flowing time which I never forgot.

Once Mrs. Mostofi closed her notebook and the line formed - from where she stood to the door - she went back to her desk and grabbed a long wooden ruler from a drawer. She wore the same look my father did in moments following a mistake either my mother or I made. She raised the ruler in the air with one hand and called the first girl in line with the other hand. “Your palms,” she said.

The girl didn’t move and hid her hands behind her back.

“Mehri, I told you to show me your palms,” Mrs. Mostofi yelled.

The sound of Leila’s heavy breathing overshadowed my own gasp; still it didn’t break the thick silence in the classroom.

Finally -- exposed, deceived, and defeated – Mehri gave up her spunk, stepped forward, crying, and raised her hands. Leila howled like a wounded dog, and all of us, in line or not, followed her lead.

It was the first lesson I learned on my first day of school: Going over each detail of my homework, finishing up the spelling check and writing the words the exact way Mrs. Mostofi expected, repeating the sentences of the first lesson: “My name is Sara. Father brings the bread. Mother cooks the dinner. I love my doll,” one hundred more times.

I knew I was going to be safe as long as my homework was perfect, as long as Mrs. Mostofi remained our family’s friend. As long as I didn’t object to her love -- each time she noticed my existence -- letting her claw my face. As long as I accepted her generosity by shoving her bitter candies down my throat. As long as I hoped -- and I prayed fiercely – that she would skip my name, that she would leave me alone on a bench, that she would give me the chance of becoming a witness, an accomplice, watching Leila’s misfortune, hiding my gratification, my conceit, my transcendence.

From that day on, every day, I shared Mrs. Mostofi’s act of purification, observing the line of the dehumanized, impatient for the echo of the school bell. Still, as their turn arrived, each one raised hands in the air without objection so Mrs. Mostofi didn’t have to scream or break a nail; she was a petite woman, a skinny, petite woman, but she used her utmost brutality to punish them for their hierarchical sins, offering a moment of blamelessness.

Two years later we left that small world and moved to Tehran where my father lost his reputation and authority, where for years, he missed his golden times of being someone influential, where we all became unidentified, undistinguished, and squeezed, just like Leila, just like Mrs. Mostofi’s maid -- just like any other little man -- waiting for the time of our punishment to arrive.

| Recently by Azarin Sadegh | Comments | Date |

|---|---|---|

| Life Across The Sun | 11 | Jun 11, 2012 |

| The Enemies Of Happiness | 12 | Oct 03, 2011 |

| Final Blast At the Hammer | 13 | Jul 18, 2011 |

RECENT COMMENTS

IRANIANS OF THE DAY

| Person | About | Day |

|---|---|---|

| نسرین ستوده: زندانی روز | Dec 04 | |

| Saeed Malekpour: Prisoner of the day | Lawyer says death sentence suspended | Dec 03 |

| Majid Tavakoli: Prisoner of the day | Iterview with mother | Dec 02 |

| احسان نراقی: جامعه شناس و نویسنده ۱۳۰۵-۱۳۹۱ | Dec 02 | |

| Nasrin Sotoudeh: Prisoner of the day | 46 days on hunger strike | Dec 01 |

| Nasrin Sotoudeh: Graffiti | In Barcelona | Nov 30 |

| گوهر عشقی: مادر ستار بهشتی | Nov 30 | |

| Abdollah Momeni: Prisoner of the day | Activist denied leave and family visits for 1.5 years | Nov 30 |

| محمد کلالی: یکی از حمله کنندگان به سفارت ایران در برلین | Nov 29 | |

| Habibollah Golparipour: Prisoner of the day | Kurdish Activist on Death Row | Nov 28 |

Thanks Mehman!

by Azarin Sadegh on Sat Sep 06, 2008 01:10 AM PDTThank you so much for your detailed feedback of my story.

It is so refreshing to see a feedback like yours, where your deep sense of observation goes beyond the simple plot, to find new layers within the obvious layers of the story.

Unfortunately, I grew up in a society where Mrs. Mostofi represented the norm and my silence too. It took me years to overcome my fear of speaking (my mind), and my deep desire of being invisible (that I took for my fear of "being")...but it is another story by itself!

Thank you!

Azarin

Revealing

by Mehman on Fri Sep 05, 2008 10:56 PM PDTThis is a well-made short story with great psycho-sociological connotations. The plot of the story mirrors the structure of power relations in an authoritarian society. the societal cells embody and reflect, in a minuscule scale, the legal and political power relations latent in the society’s grand echelon. What interests me most about this story is the way the psychological diagnosis of the characters and the power relations in the classroom would disclose the profound psychological diseases prevalent in a typical 'developing' society.

The cruelty of the protagonist (Mrs. Mostofi), her extreme mental anomaly and her unquestionable habitude of torturing the kids for no crime or for petty crimes is stunning. More amazing is the narrator’s sincere reactions to the horrific acts; she is scared, she does not want to do anything to change the situation, she can not do anything to change the situation, nor can anyone else do or want to do anything to protest or change the situation.

The punishments are all routine events, they must happen in every class and it is assumed by all students and Mrs Mostofi to be her ‘natural right’ to torture them; in fact it is not called torture, if you ask her or any of the students. Mostofi would probably say: “ Oh, you mean that little punishment, it’s good for them, they need that to be purified… If you do not believe me you can go and ask the students themselves… When they grow up they will all come and thank me for that.” And if you ask the students, given their age, situation and the state of mind they live in, they would probably all consent to the horrible acts as a necessary step for their progress.

Much more could be said about this profound tale. The story is great and the author has developed it very well.

Azarin

by Zion on Wed Sep 03, 2008 10:52 PM PDTI really enjoy reading your pieces. You are one of the few writers here that I really look forward to read. I know how hard it is to get a novel done and published, but I'm sure you can do it and you will easily find publishers for it. We are waiting. :-)

Thanks...but it seems that writing a novel takes forever!

by Azarin at work (not verified) on Wed Sep 03, 2008 02:32 PM PDTThanks Feshangi Jan for your nice comment!

But between us, I like writing fiction better than my own experiences...it's less painful :-)

Dear Zion,

Thanks a lot for showing so much support and interest in my novel-in-writing!

One of my novel class classmates just finished her final draft. It took her 3 full years to make this accomplishment. But we have to know that she’s American and it is not her first novel and she already has an agent. Still…she think it's going to take another year (and if she's lucky)for her book to come out!

And in my case? I started writing my novel in April 2007 after living in this country for only 11 years!

It means that unfortunately I still have years to finish it and in today's world of publication, there's no guarantee for any book to find a publisher!

So my dear Zion, as you see there's still a long way to go before I can actually offer you my novel! But I am very much appreciative of your nice intention!

Azarin

Sad and Lovely

by Zion on Wed Sep 03, 2008 01:45 PM PDTThanks. When do we get to read your novel?

Dear Azarin

by Feshangi on Wed Sep 03, 2008 11:18 AM PDTI really enjoyed reading this story on several levels. Now that I have read a number of your stories I can say that I particularly enjoy the ones that come from your own experiences. They are vivid and full of colour and texture, like a painting. It is easier for me to visualise the story. On the personal level, it reminded me of myself hating to go to school since I was a very bad and tanbal student who spent more of his school days outside the headmaster's office than in the classroom. Thank you for the story.

Feshangi

Thanks to all of you!

by Azarin Sadegh on Wed Sep 03, 2008 10:40 AM PDTDear Jamshid,

Thank you so much for your kind words! I guess you are referring to my older essays before we switched to the new format on Iranian.com. Between us my own favorite is the one with Cucumbers...anything that I've written about my father makes me happy and sad at the same time...

Dear Tahirih, I really appreciate your touching feedback! Thank you! This page is a short story inside a longer story. Actually my novel is composed of many many stories like this...and I am so sad that this experience (which is my own experience on my first day of school in Shahi/Mazandaran) is the experience of many of us. But i am also happy to be able to share it with others...because I think as soon as I start talking about these old wounds, their poison and pain starts going away.

My Dear Nazy, What can I say after reading your moving (and so beautifully and so well written) comment?

Unfortunately, I (like many of us) grew up witnessing similar violence and I was told that it was just “normal” and it was my first contact in a social situation as an independent individual (No, I didn’t go to “koodakestan”). No wonder I turned to become too shy and too scared of the world as a kid. No wonder I found refuge in the fictional world of books and imaginary heroes…:) And before I forget I have to thank you so much for being the voice of wisdom on Iranian.com! You’re like the soul of IC… Thank you for being you!

My dearest friend, “Irandokht”,

First I have to thank you for accepting to accompany me to Hollywood Bowl last night! It was an absolute joy!

Second, didn’t we talk about feeling of belonging to a special kind of group with emotional issues on IC “that teemarestan thing!!”? Maybe this feeling has to do with where we come from and which type of childhood we had and which type of wound is scarring us…what ever it is, I just hope that one day we will get rid of these memories, or at least they don’t hurt us anymore…

My dear Niki,

Thank you so much for being always so supportive for whatever I write! And I am so sad that we shared the same type of sin: being a witness and feeling like an accomplice to this violence. But you my dear…you just look so healthy and so balanced (unlike me that I have been called otherwise..:))

Thanks again to all of you and I just feel so bad about such a long thank you note!

Azarin

the smell of stale nicotine

by nikinotlogged in (not verified) on Wed Sep 03, 2008 09:04 AM PDTMy second grade teacher did not use the wooden ruler but she would routinely slap, pull ears and most humiliating of all, send you in the corner if you failed her pop quizzes or could not recite yesterday's grammar rule by heart. I still can remember her severe pageboy haircut, and her breath and clothes imbibed forever with the smell of stale coffee and nicotine.

She was not the only abusive teacher I had (will write blog later on that topic) but her type leaves as much of a mark and influences your life as all those other great teachers who could teach you to love and appreciate the pursuit of knowledge.

Thank you for your writings, as always.

I wonder....

by IRANdokht on Wed Sep 03, 2008 12:08 AM PDTit's a wonder that faced with such physical, emotional and verbal abuses that were the norm of our times, some of us grew up achieving so much in life, or is that why our generation is stuck in this dysfunctional state right now, knowing what we know , hiding our scars even from ourselves... I don't remember having witnessed the physical abuses but there were always a lot of pressure, emotional and verbal abuse that would horrify the child psychologists of our today's world.

are we all in need of serious therapy? would we behave differently and treat each other with more love and care if we help ourselves find a closure for all the bitter memories...

I only wonder what we could achieve then.

Thanks Azarin jan for reminding us of what ails our souls with your eloquent writings.

IRANdokht

PS: on a more personal note, thank you my dear for a wonderful experience tonight! It was great spending such quality time with you :0)

The Scars...

by Nazy Kaviani on Tue Sep 02, 2008 07:12 PM PDTAzarin,

No one really heard the sound of the wooden ruler coming down in the air and touching a skinny little girl's hands...

No one saw the menace of a teacher or a principal who felt entitled to punish a child so...

No one ever reported this violence...

The violence was not discriminatory to poor girls or those with uneducated parents...

The violence had to do with the victory of authority over initiative, energy, ambition, and joy of life...

The violence had to do with being different and being forced to conform, even if you had scored 20 in everything; even if you received tens of Kart Afarins for your grades...

I couldn't read time on a clock...

I didn't know how to be patient, how to wait for it to end...

My heart is scarred with being a victim and a witness of that violence for the rest of my life.

My heart ached while I was reading .

by Tahirih on Tue Sep 02, 2008 06:21 PM PDTI am sure we all have had a Mrs Mostofi in our school years. So sad that they had no knowledge about children and how to help them to reach their potentials. How many times we have seen Leilas being punished for , not being perfect.

you write ,like a river moving so nicely and swiftly. Such a gift you have, and at the same time you touch where it hearts, but do it with such grace.

Really enjoyed it. Thanks.

Tahirih

Azarin

by jamshid on Tue Sep 02, 2008 06:05 PM PDTNice! As usual, I enjoyed reading your work.

A while back in another thread, you made a reference to one of your stories, one which I must have missed. After I clicked on your name I discovered that there were many others I had missed.

I wish there was a better way to track others' work. However, on the upside, it was nice to find out there is much food on my plate to read.