به زبان فارسی

PICTORY

LATEST MUSIC

SEARCH

Wither Iran?

by Homa Katouzian

12-Aug-2009

The title of this short article is somewhat misleading since prediction regarding anything Iranian is a hazardous task and is often refuted by the following events. The reason is that Iran is, as I have described it, a short-term society, a society which lacks continuity both at the individual and social level. I once wrote that up to a century ago, when an Iranian man left home in the morning he would not know whether, by the evening, he would be made a minister or be hung, drawn and quartered. I also wrote, on another occasion, that an Iranian may be a merchant this year, a minister next year, and a prisoner the year after. Obviously these are exaggerations, but they are close to the Iranian experience throughout its long history; a history which, though very long, consists of connected short terms. Ask an average Iranian what he would be doing in six month’s time and you would normally receive the reply ‘In six months’ time who is dead and who is alive’.

In the 1970s many if not most Western journalists, analysts and academics used to describe Iran as ‘an island of stability in the Middle East’, a Western economist even went as far as predicting Iranian gdp, rate of growth, etc., in the year 2000. In the late 70s the entire Iranian society rose against the state and overthrew it. Since then, there have been countless predictions about political developments in Iran almost all of which have turned out to be off the mark. In 1997, a totally unexpected landslide electoral victory swept the Islamic reformists into power. Many believed that that was ‘the beginning of the end’ for the Islamist regime. Eight years later, a fundamentalist was elected president, and although there were some complaints about electoral irregularities, hardly anyone denied that he had had a large share of the votes.

Let us begin with a brief account of the background to the present situation. In 1979 all shades of opinion combined to bring down the Pahlavi state. No social class and no political party stood against the revolutionary movement, and 98 percent of the people voted for the establishment of an Islamic republic. But almost at the same time fundamental differences began to emerge among the revolutionary forces such that by 1982 all but the Islamists had been eliminated from politics. There were conservative and radical tendencies among the Islamists themselves but their differences rarely came to the surface in the 80s, partly because of the necessities of the long war with Iraq, but mainly perhaps because of the unifying role of Ayatollah Khomeini who acted as the regime’s supreme arbiter.

The end of the war in 1988 and Khomeini’s death in the following year began a new era in the politics of the Islamic Republic. At first the union of the conservative Ali Khamenei as supreme leader and the pragmatist Ali Akbar Rafsanjani as president seemed to work fairly well but, especially in Rafsanjani’s second term of office (1993-1997), the conservatives began to show dissatisfaction with his policies. Apart from the conservatives, however, two other distinct factions had emerged in the 90s: the fundamentalists and the reformists. The fundamentalists – mainly representing the traditional lower and lower middle classes – tended to emphasise the Islamist nature of the regime, advocated an anti-Western foreign policy, and championed the cause of ‘the downtrodden’: ‘death to the capitalist’ was a favourite slogan in their street demonstrations. The reformists, on the other hand, displaying an Islamic social-democratic outlook, believed in a more open society and (later) better regional and international relations. The conservatives were closer to the fundamentalists on their religious and foreign policy views; the ‘liberal’ pragmatists were more in line with the reformists on both domestic and foreign policy issues, although in more moderate and accommodating terms.

Contrary to all predictions, the 1997 presidential election resulted not in a conservative but a reformist-pragmatist victory. Women and young people certainly played an important role in the reformist campaign but the landslide victory reflected the aspirations of most of the voters – both religious and secular – for change. Yet it was not, and could not be, an Iranian ‘Thermidor’, as some of the more historically conscious Western commentators rushed to describe it, if only because the supreme leader, the Revolutionary Guard, the ultimate legislative authority (Council of Guardians), the judiciary, and considerable business and property interests were on the side of conservatives. Khatami won another landslide victory in 2001, but while he brought about significant changes in domestic and foreign policy, he had few friends left in the last two years of his presidency, since the conservatives and fundamentalists used all in their power to limit his options, while at the same time most of his constituents accused him of lack of faith for not delivering the moon. During an address in November 2004 to a meeting at the University of Tehran, Khatami was booed and heckled, some students shouting ‘ Khatami, you liar, shame on you’. Yet, if only to prove the short-term nature of Iranian society, when he went there again in 2007 – the second year of Ahamdinejad’s presidency - the crowd were shouting ‘Here comes the people’s saviour’.

Ahmadinejad was a fundamentalist and the candidate of a fundamentalist-conservative coalition, and his election once again caught many of the Iran observers in the wings. Posing as a man of the people and promising increased welfare for the lower strata of the community, he won most of their votes while at the same time attracting the support of powerful conservatives who wanted to be rid of the reformists at all costs. That is why while the conservatives generally applauded his reversal of the reformist trends in domestic and foreign politics, they not infrequently displayed their displeasure at his economic policies, his millenarian views, his abrasive personality and his overtly self-confident behaviour. In 2009 a leader of a solid conservative group – the Islamic Coalition Party - made this clear when he said that, despite serious reservations, they would back Ahmadinejad’s nomination for a second term solely in order to stop a reformist victory.

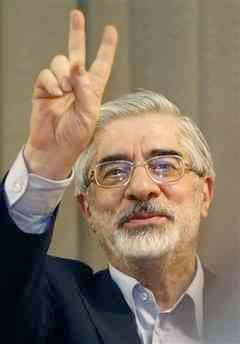

Four years of Ahmadinejad’s domestic and foreign policies taught the reformists and the secularists a hard lesson. They stopped saying that Khatami had ‘done nothing’ and became nostalgic about his time as president. The majority of reformists and secularists wanted Khatami to stand. Yet by February 2009 they did not have a candidate for the June election. Under great pressure, Khatami first came forward but then stepped down in favour of Mir Hossein Mousavi, a radical prime minister of the 1980s. Backed by the pragmatist faction as well, Mousavi’s campaign started late through a very slow process and –as further proof for the short-term nature of the society – it was only about three weeks before the election day that it began to take off the ground. And even as late as that, no-one could have predicted anything remotely close to the imminently unfolding events.

The electoral dispute that followed is now well-known history and need not be recounted in this brief. It was however a major turning point in the history of the Islamic Republic as it had not experienced anything like it since the power struggles of the early eighties. The factional struggles during the Khatami years were at most a crisis of authority. But now there was a crisis of legitimacy as well, since the Islamic regime had split down the middle, each side claiming legitimacy and –at least implicitly- denying legitimacy to the other side. This was the first time that the reformist-pragmatist coalition had drawn very large crowds made up of both their own supporters and secularist people to the streets, so that the movement could no longer be regarded as that of the Islamic reformist-pragmatist factions, but a wider one, also representing the secularists who had accepted the leadership of the reformists. On the other hand, the supreme leader’s unequivocal backing for the declared election results as well as Ahmadinejad himself changed his usual posture as an arbiter of factional disputes to one that was identified with the fundamentalist faction, and in effect dragged him into factional politics.

At the political-cum-ideological level the reformist leaders stressed the representative and republican features of the system, whereas the fundamentalists put the emphasis on the authority of the supreme leader as representative of the Hidden Imam’s, and thereby God’s, authority. This brought to surface the unresolved dichotomy between the ‘republican’ and the ‘Islamic’ features of the constitution. Thus, the reformists accused the fundamentalist-conservative factions of a ‘coup’ against the republic, while the latter launched a systematic campaign to describe Mousavi and his supporters as pawns – if not puppets – in a Western conspiracy to bring about a ‘velvet revolution’ in Iran, comparing the events with those in Ukraine and Georgia which had led to the establishment of pro-Western government in those countries.

Warnings about ‘velvet revolutions’ dated back to a couple of years before. And the belief in conspiracy theories is a major characteristic of Iranian politics and society, almost regardless of political affiliation. Western media generally supported the protest movement, but however that may be, there is no evidence –notwithstanding the current show trial confessions and recantations which would not stand up in a proper court of law - that the movement had been organised or owed its existence to foreign conspiracies.

‘The politics of elimination’, as I have termed it, is also a long-standing feature of Iranian politics. Clearly the protestors are in no position to eliminate their rivals from politics even if they so wished. On the other hand, and by the very nature of their ideology, the fundamentalists would not shy away from the political elimination of their opponents if they can. What stands in their way is both the support of quite a few senior ayatollahs for the reformists and the fact that a considerable body of relatively moderate conservatives would not wish to go that far. Hence the present contradictory situation when a considerable number of leading reformists are on show trial, while Mousavi and Khatami are still at large and active, and many senior conservatives have cast doubt on the validity of the charges and trials. Forecasts which promise the imminent fall of the Islamic regime, or ‘the beginning of the end’ for it, are premature and often based on optimistic sentiments even when they come from otherwise serious analysts. There is at present no major external threat to the regime, and as for the domestic forces, the ruling parties have under their command the armed, police and intelligence forces, the economy, the parliament and the judiciary, not to mention the fact that they too have a base in society.

However, I would return to the point that I made at the opening of this piece that things can always happen to Iran and Iranians which are beyond rational expectations. It is not for nothing that Iranians themselves call it ‘the country of possibilities’.

This paper will be published in forthcoming issue of Oxford Forum, (October 2009).

AUTHOR

Currently based at the University of Oxford, Katouzian is a member of the Faculty of Oriental Studies and the Iran Heritage Research Fellow at St. Antony's College, where he edits the quarterly journal Iranian Studies. He is also a member of the Editorial Board of the Comparative Studies of South Asia, Africa and the Middle East.

| Recently by Homa Katouzian | Comments | Date |

|---|---|---|

| Private Parts | 3 | Nov 04, 2009 |

| Beyond the Old and the New | 4 | Sep 04, 2009 |

| Man and Animal | 1 | Aug 05, 2009 |

RECENT COMMENTS

IRANIANS OF THE DAY

| Person | About | Day |

|---|---|---|

| نسرین ستوده: زندانی روز | Dec 04 | |

| Saeed Malekpour: Prisoner of the day | Lawyer says death sentence suspended | Dec 03 |

| Majid Tavakoli: Prisoner of the day | Iterview with mother | Dec 02 |

| احسان نراقی: جامعه شناس و نویسنده ۱۳۰۵-۱۳۹۱ | Dec 02 | |

| Nasrin Sotoudeh: Prisoner of the day | 46 days on hunger strike | Dec 01 |

| Nasrin Sotoudeh: Graffiti | In Barcelona | Nov 30 |

| گوهر عشقی: مادر ستار بهشتی | Nov 30 | |

| Abdollah Momeni: Prisoner of the day | Activist denied leave and family visits for 1.5 years | Nov 30 |

| محمد کلالی: یکی از حمله کنندگان به سفارت ایران در برلین | Nov 29 | |

| Habibollah Golparipour: Prisoner of the day | Kurdish Activist on Death Row | Nov 28 |

.

by timothyfloyd on Wed May 12, 2010 12:44 PM PDT.

Dither ,neither, nor for Iran?

by fatemeholfati on Sun Sep 06, 2009 03:07 PM PDTKatouzian short but concise article is strong on facts and background to the exsisting post election problems. We have to agree with him that, elimination of all the opposition group since 1982 has been perfomed surgically and consistantly by the IRI.

No one has the magic crystal ball but after 30 years of fundementalist ideology: a mish-mash of Western style legacy machinary and administration with a venear of past-by-date Taliban style fundementalism, are we witnessing a slow deathof IRI? Katouzian puts it succintly Iran revolution became Islamic only after the US embassy seige. The price paid for that ugly act is immeasurable today and US policy will play a vital role in the upcoming events.

Smoke and Mirrors

by Ahura on Sun Aug 16, 2009 09:39 PM PDTIn the Islamic Republic of Iran the labels of fundamentalist-conservative and pragmatist-reformist groups and their corresponding advocacy of ‘Islamic’ and ‘Republic’ aspects of the IRI constitution, as elaborated in this article, is merely a mirage and nothing more than a fight over power to rule by these islamists. Other Islamic scholars elaborate on this classification of vali-e-faghih as ‘appointed and absolute – entesabi va motlagh’ in contrast to ‘elected and conditional - entekhabi va mashroot’, albeit the viceroy of God in the absence of 12th imam. These classifications translate into selected by the assembly of experts and given absolute say, or still assigned but somehow conditional on pursuing the people’s wishes (an explanation few grades above my comprehension!) The easier explanation is “smoke and mirrors.”

May be Dr. Homa Katouzian could elaborate on the specific articles of IRI constitution that makes such distinction of ‘Republic’ (implied people’s rule) and ‘Islamic’ (implied rule of vali-e-faghih) along with possibilities of basic change. From a quick read of IRI constitution one sees Article 5 as rule of the vali-e-faghih, Article 109 his qualifications, Article 110 his powers, and Article 177 the permanence of this velayat-e-faghih excluding it from change through referendum (along with many other aspects of IRI constitution which keeps this theocracy safe from aspirations of people for change.)

Kaveh, re. Dabashi

by Jaleho on Sun Aug 16, 2009 04:18 PM PDTAlthough I respect Dabashi for his work (I liked his book Iran: A People Interrupted), yet parts of his book that has to do with Islamic Revolution, and even worse, his reaction to recent election to me is quite off. Strangely enough(considering these people's past writings), regarding Iran's current situation, I find some of Amir Taheri and Fukuyama's take, the most accurate of all the experts!

Again, since I wrote my opinion about Dabashi's take on the election in Iran following his article here: The Left is Wrong, I'll just copy my comment.

//iranian.com/main/2009/jul/left-wrongpage1

Here's Mr Dabashi's problemby Jaleho on Sat Jul 18, 2009 05:37 PM PDT

Mr. Dabashi is a respectable and clever observer of the events so far as he's removed from them in space-time. That makes him a good observer of history of sort. Thus, in retrospect, he is in line with just causes, be it the Palestinian cause, or sympathizing with most colonial injustice of the past, including the Iran prior to Islamic revolution. But, when it comes to PRESENT event, in particular the events that he is in proximity of both in space and time, his far sighted vision become myopic! That is a characteristic of a person who can be a good writer, but a weak leader.Mr. Dabashi might see even the more "recent historical events" like the orange revolution in a more realistic light. For example, in the orange revolution, despite the fact that Yanukovych had far less real lead over Yuschchenko than Ahmadinejadhad had over Mousavi, he seems to be more sympathetic to Iran's "green revolution." The proximity of events in Iran to his heart blinds him to the degree that he blames everyone whose opinion he's been respecting hitherto. He calls them ignorant of events of Iran with a logic that Netanyahu could use on Mr. Dabashi regarding events in Israel.

Despite my high regards for Mr. Dabashi for his historical analysis, his foggy vision with regards to events in space-time near and dear to him, make him lag behind visionaries like Edward Said. In recent events of Iran, unfortunately he's closer to pseudo-intellectuals and "artists" of the type of Makhmabaaf than anyone of the stature of Said. He better reserve his analysis on Iran limited to films and cinema critique than actual historical and political events. The fact that MILLIONS of Iranian youth are expressing their pent up frustration afforded by more internal security, and feel a bit of freedom of expresssion ignited by pre-election debates, should not confuse Mr. Dabashi from the actual dynamics of Iranian events.

Afshin and Kaveh

by Jaleho on Sun Aug 16, 2009 03:53 PM PDTMr. Katouzian has already made his detailed review and the way he sees Islamic revolution in his Feb. article. We had quite a few interesting back and forth in that thread of his. I explained my view of where I disagree with him in those comments too, so won't bother you here again. If you're interested, here's his article:

//iranian.com/main/2009/feb/iranian-revolution-30

Spark has kinkled the tinder

by NASSER SHIRAKBARI on Sun Aug 16, 2009 09:56 AM PDTI see all elements of a revolution has overtaken the arena of Irans struggles for freedom except one. As I had mentioned on my article of August 5, " Final Show Down", four more years of Ahmadinejad, might take care of the last element...when the knife reaches the bone, then nothing matters.

Afshin,

by Kaveh Parsa on Sat Aug 15, 2009 06:30 PM PDTRead this. more my cup of tea!

//weekly.ahram.org.eg/2009/960/focus.htm

thoughtful comments ramintork

by benross on Sat Aug 15, 2009 03:20 PM PDTBut do not give up on secularist movement. You don't know how fast and furious the public opinion changes. In Islamic revolution, those who gave credibility and strength to the movement were basically secularists, the flawed ones -now we know the hard way- but with no affiliation with political-religious thinking.

Don't give-up on current uprising. The movement of the new generation is essentially a secularist movement without being articulated. It needs likes of you to help it finding its true essence... and it will find it.

Kaveh

by Afshin Ehsanpour on Fri Aug 14, 2009 10:24 PM PDTIt would wrong and unfair to blame the tragedy of the Islamic Republic on the “intellectual left”. For sure, the leftist revolutionaries helped the movement for democracy and independence get started; however, they were swept aside by forces beyond their control. And by this, I mean the forces of tradition which Shah’s “Persianism” and mechanical modernism had tried so hard to sweep under the carpet. During the revolution, the tradition came back with a thunder—the Freudian notion of the “return of the repressed”—and took its revenge.

Jalelo & Afshin

by Kaveh Parsa on Fri Aug 14, 2009 04:05 PM PDTNo problem with his measured thinking, especially the history lesson which makes up the bulk of this piece and for which I thanked him in my earlier comment. As much as I like a good read and he is always a good read, I have learned to take his conclusions with a pinch of salt! He was my teacher at Uni. In this piece there is no conclusion.

I was also pointing out that it was his and the pink revolutionaries (intellectual left) measured thinking that helped get us to where we are today. Except for Milani, I consider all the other characters you mentioned as Iranian-American TV pundits whose analysis and punditry is influenced more by the American part of their identity than the Iranian part. TV punditry doesn't leave a lot of room for measured thinking! As for Milani I think he is a right wing version of Katouzian.

I agree with you on Sazgara.

KP

Well informed, good analysis but doesn't add anything new

by ramintork on Fri Aug 14, 2009 04:00 PM PDTThis article is a good analysis but other than providing a good insight, it does not forecast nor does it claim to forecast a new outcome from an expert in the field.

To summarize the article claims that it is in the nature of Iranian and more specifically IRI politics to exist in a state of perpetual flux, and advises one not to be hoodwinked into thinking that this juggling act would result in falling girating plates.

However, Iranian politics has certain rules. Iranian politics is driven by Populism and it is reactionary in that it echos current Westen politics if they impact its security. Unpredictable yes, but even the chaos theory has certain predictability!

Now given that EU and US for economic reasons would favour a Khatamiesque IRI, that has no nuclear ambitions and does not pose a threat to Western allies and that they would not gamble in supporting an unkown new entity in the form of Federal Republic of Iran, given that they are planning super harsh sanctions, one would predict that even the hardliners after they have their show of strength would try to emulate the reformists and walk their walk at least in coming to their direction for the sake of their common survival.

Given the choices I think the analysis of the other experts that Iran would either tighten up like North Korea or open up like China is more realistic, the bad news is that I am a secularists who is watching the lights in our corner slowly go off and neither option is promising.

varjavand

by Ari Siletz on Fri Aug 14, 2009 12:32 PM PDTI sense hopeful signs that the software bug Katouzian has drawn our attention to can be fixed to where "dynamic" would be the right word.

Jaleho

by Afshin Ehsanpour on Fri Aug 14, 2009 12:10 PM PDTI liked your response to Kaveh. My sentiments exactly!

@benross: Very

by vildemose on Fri Aug 14, 2009 09:01 AM PDT@benross:

Very funny.

@Kaveh Pars:

Excellent observation. Kolangi culture most certainly applies to most countries since the Industrial revolution. The US has one the most Kolangi or what I call Disposable culture of any nation.

I liked the article,

by varjavand on Fri Aug 14, 2009 08:18 AM PDTI liked the article, well-balanced. However, I would change the term short-term with dynamic. It is in fact the dynamism of the Iranian society that activates people’s sense of discontent with status quo, they thus seek something new. The writing has also the distinguishing mark an article written by an economist; no clear conclusion. There is a famous phrase stating that “if you lay all economists end-to-end, they would not reach a conclusion”

Varjavand

Ahmed from Bahrain, you said,

by Jaleho on Fri Aug 14, 2009 08:16 AM PDT"It is not a question of if but when."

I hope you notice that this inane slogan is true for everything in the world! Nothing is forever static.

I hope you are not one of those who predicted a market crash in the US since 50 years ago; there were many of those "correct" people who got wiped out when US markets had its biggest boom in that period as well :-)

Kaveh, you said,

by Jaleho on Fri Aug 14, 2009 08:00 AM PDT"This article is essentially a very brief history of Iran in the last 30 years (thanks Mr Katouzian) followed by a 3 line prediction and then a 3 line qualification as to why that prediction might not come to pass.

he really can't go wrong can he? "

That is very true, in particular NOW that as they say, "abha az asyab oftadeh ast," kinda. However, this measured thinking is far better than other "Iran experts" like Milani or Vali Nasr and the new wanna-bes like Aslan or Sadjadpour who went to TV shows and made perfect public clowns out of themselves by their repeated WRONG predictions, propaganda, and wishful thinking which showed how disconnected they are from Iran's REALITIES.

Listening to someone like Sazegara's description of the revolution that was supposed to take place on the day of Ahmadinejad's confirmation, his spirited directions for what HIS "people" should do the day after.....you wouldn't know if the CLOWN was serious or simply delusional and thinking of himself leading a revolution from afar!

Just listen to see how delusional wishful thinking can make a public ass out of a person!!

//iranian.com/main/blog/khaleh-mosheh/sazegara-action-tomorrow

Ari

by Mort Gilani on Thu Aug 13, 2009 09:00 PM PDTThanks for your correction, and my apologies to Mr. Katouzian for the error.

Mr Katouzian

by Kaveh Parsa on Thu Aug 13, 2009 08:14 PM PDTwas one of those leftist intellectuals who was hoodwinked by khomeini and was all for tearing down rather than renovation (to use his own jame e ye kolangi metaphore) at the last turning point in our history.

This article is essentially a very brief history of Iran in the last 30 years (thanks Mr Katouzian) followed by a 3 line prediction and then a 3 line qualification as to why that prediction might not come to pass.

he really can't go wrong can he?

Mort

by Ari Siletz on Thu Aug 13, 2009 06:59 PM PDTWhy Metaphor Instead of Common Sense?

by Mort Gilani on Thu Aug 13, 2009 06:13 PM PDTDear Ms. Katouzian:

With all due respect, I think you failed to see the elephant in the room. The “major threat” to the Islamic Republic is neither an external military threat, nor the outcome of infighting between political factions. The most serious threat to AN regime is an economy that is running on fume with 20% inflation and 25% unemployment. We’ll see in few months how the government is going to pay for all goodies with which they could buy votes. The Islamic Republic would collapse even with “reformists” in charge. Iranian economy needs an ABSOLUTE fundamental overhaul that can only be implemented by a government that puts the welfare of Iranians before an ideology, but that is not in the nature of an Islamic government.

Well informed thinking.

by Ari Siletz on Thu Aug 13, 2009 05:41 PM PDTKatouzian has an interesting Persian phrase for "short-term society." The scholar calls it "jame e ye kolangi." In reference to old houses in Iran being called "kolangi" instead of "historical structures," as they are sometimes called in California. The latter term encourages renovation, while the former is about tearing things down. This is more than a metaphor for the difference beween a build-and-destroy political heritage and a build-and-improve mindset.

And the point is?

by benross on Thu Aug 13, 2009 05:25 PM PDTThe beginning of the end of this regime doesn't mean the imminence of its end. If this is the point, well taken. For the rest, I don't see why we should constantly recount what we read in newspapers. What *we* should do from here on? This is something to be discussed.

We just have too many observers and very few things to observe.

Very well written

by Mehdi on Thu Aug 13, 2009 03:31 PM PDTI think the writer has avery good grasp of what is going on in that country and the reactions of the outside world. I wish more people could be so logical and less emotional.

It is not the question of

by Ahmed from Bahrain on Thu Aug 13, 2009 01:21 AM PDTif but when.

No system endures when based on injustice. Iran will eventually be ruled by its people for its people. ANd when it emerges, it will be a beacon for the rest of the Middle East to aspire to, if not the world.

Mark my words. It will happen. The writing is all over the wall.

Ahmed from Bahrain

Dead on!

by Shahriar Zahedi on Wed Aug 12, 2009 10:16 PM PDTHoma Katouzian's analysis is dead on. The islamic regime's hold on the judiciary, the parliament, the nation's economy, and its considerable support base in the heartland all not withstanding, it's also an undeniable fact of history that any regime with a dedicated and well-fed police and intelligence aparatus can remain in power indefinitely.

finally, a level-headed

by liberation08 on Wed Aug 12, 2009 08:03 PM PDTfinally, a level-headed analysis about the potential, or lack thereof, of regime change in iran is posted on iranian.com for me to see. those who believe the regime's collapse is inevitable are thinking far too wishfully

IRI's collapse is inevitable

by Farhad Kashani on Wed Aug 12, 2009 07:30 PM PDTIRIs collapse is inevitable for the following 4 reasons:

1- It has lost all credibility, legitimacy and reputation in the eyes of Iranians and the world.

2- The Iranian people simply do not want this regime in power for countless obvious reasons, and the group that is leading the people’s uprising against the regime, the students, have absolutely nothing to lose. And if you have nothing to lose, it will be very difficult to defeat you.

3- The International community has no option but to treat it differently now. They might have to deal with it, but the public opinion against it and focus on it are so strong that it would simply not be the same. The IRI regime will have to give in, sooner or later. In today’s world, there is no place for Fascist regimes such as IRI. IRI, N Korea, Cuba, Zimbabwe and similar regimes are hanging to a very thin thread for their lives. That thread will eventually break off under domestic and international pressure.

4- The unity among the regime different elite groups has shattered forever and is irreparable. Many of the former regime big players want drastic change. They are tired of status quo and so is the Iranian people. Many of them feel the regret for past actions and want to set things straight. Many have matured from being a revolutionary to a politician or a reformer. The regime cannot simply be put back together.