به زبان فارسی

PICTORY

LATEST MUSIC

SEARCH

The New Dress

by Azadeh Azad

13-Dec-2011

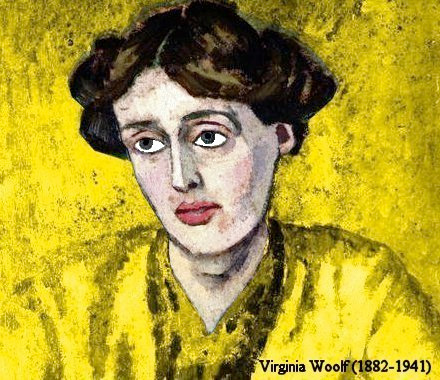

In Virginia Woolf's 1924 short story The New Dress the main protagonist, middle-aged Mabel Waring, arrives at a high-society London party. She removes her cloak, catches sight of herself in the mirror after the servant, Mrs. Barnet, passes it to her "perhaps rather markedly"(1), and is unexpectedly flooded with strong feelings of shortcoming, mediocrity and fear.

These depressing feelings are triggered by apprehension that her new yellow dress is not suitable for the party, which is thrown by her wealthy and socially distinguished friend, Clarissa Dalloway. So, after greeting the cordial hostess, she rushes to a mirror at the back of the room to eye herself and is consumed with despair at the belief that there is something definitely wrong with the dress, although she has no clue as to what the problem is.

Mabel obsesses over what other guests, all voguishly dressed, must be thinking about her new dress and pictures them being appalled over it. She scolds herself for deciding, "why not be original? Why not be herself, anyhow?"(2). Upon accepting the fact that she does not have the same means as high-society women and cannot afford a fashionable dress, laudable by others. She has had a yellow silk dress made by her dressmaker, Miss Milan, from a pattern in an old fashion magazine of her mother, which she feels reflect her character (3). She has spent long hours with Miss Milan at a stuffy workplace trying to make the design perfect with the hope of projecting a perfect image of herself in the party. Now, she tortures herself with fixated ideas of her mindlessness, which merits "to be chastised."(4).

"The New Dress" is character-driven and comes with a dull plot, but a very intense internal conflict that unfolds in Mabel’s mind. There are a few other characters, mostly minor. The story is written from an anonymous, third-person perspective and in a stream-of-consciousness style, for which Virginia Woolf was a pioneer together with James Joyce. In stream-of-consciousness literary style, the narrator knows the inner thoughts of her character and takes advantage of the privilege of omniscience by scrutinizing her emotional and psychological drives.

In this story, ideas do not develop rationally, but surface erratically, while Mabel's thoughts wander away from the party and back to it. It's brutally honest and upsetting to read Mabel’s divulging all her true thoughts and feelings to the reader. Woolf cleverly uses narrative point of view, characterization and two settings representing two social classes, Mabel’s dressmaker’s little workroom and the drawing-room of the Dalloways, to get deep into Mable’s consciousness and provide an effective portrait of an insecure woman in this little masterpiece.

The themes of the story are still relevant in our day and age. The concepts of alienation and loneliness are easily discernible, although they are the effects of the more fundamental themes of class, power, and gender inequalities. Significant metaphors of clothing, mirrors and insects are masterfully used in the story. And at a deeper level, we can appreciate the theme of the nature of "reality" itself as perceived by Mabel.

Alienation & Loneliness

Mabel’s sense of alienation appears as soon as she reaches the party. The servant identifies her underprivileged origins from her new dress and makes Mabel feel like an outsider by subtle gestures she makes. Throughout her stay, Mebel is obsessed with the thought of her alienation from members of the upper class she actually wishes to be connected to.

"…this thing, this Mabel Waring, was separate, quite disconnected;" "I feel like some dowdy, decrepit, horribly dingy old fly", she said, making Robert Haydon stop just to hear her say that, …and so showing how detached she was" (5).

She hates her dress because others do not appreciate it. Instead of viewing herself through her own eyes, she views herself through the eyes of the party guests, as if she is outside of herself or a stranger to herself.

While the other guests chat with her, an intense self-consciousness about her look and style allows her only to converse with them at a superficial level, which holds her in a bubble of loneliness. Self-absorbed, she hardly listens to other guests, but imagines they are ridiculing her. When Mrs. Holman asks her about a vacation site, it makes her "furious to be treated like a house agent or a messenger boy". Or, she is "left alone on the blue sofa,… for she would not join Charles Burt and Rose Shaw" who are chattering "like magpies and perhaps laughing at her by the fireplace"(6).

She tries to put an end to her pain, by scolding herself for worrying about what others think of her, but slips back into ideas about her own "odious, weak, vacillating character."

Social Class

When Mabel first sees herself in the mirror in the privacy of the workroom, she learns that "what she had dreamed of herself was there—a beautiful woman." She was "the core of herself, the soul of herself" (7).

However, in Mrs. Dalloway’s drawing-room, "woken wide awake to reality"(8), she perceives her image as "repulsive" and reconsiders her course of action to have been pointless . Her attempt to reinvent a self-image and her view of the "core of herself" as "a beautiful woman" are destroyed (9). Under the social coercions of the party, Mabel questions and alters her self-image. What is true is no more her original and self-made self at Miss Milan’s: "This was true," she confirms, "this drawing-room, this self, the other false" (10). Mabel’s internalized gender and class insecurities cause her to undergo a psychological transformation in the public space of the party.

Feminine Gender

The narrator brings to mind Mabel’s gender from the inside, by probing into what Virginia Woolf calls "frock consciousness" or clothing consciousness. Woolf writes in her Diary: "people have any number of states of consciousness: I should like to investigate the party consciousness, the frock consciousness. The fashion world …is certainly one; where people secrete an envelope which connects them & protects them from others" (11).

In this story, Woolf tackles the dynamic of the party and fashionability, presenting it as a sphere in which the look compromises, blocks and misrepresents self-conception. By exploring the clothing consciousness and by acknowledging that form and content are blended, Woolf uses a more experimental style to describe gender as a constructed "clothing" and to show how patriarchal and class discourse is internalized by Mabel and put into action in everyday life.

By investigating "the party consciousness," Woolf means to delve into her characters’ experiences of a collective event by producing the minds of these characters from within. Here, we find ourselves in Mrs. Dalloway’s drawing-room, yet we are seldom in contact with the ‘reality’ of this setting. Our communication with the elements of the scene takes place only through the consciousness of Mabel.

*

Metaphors in this story have crucial meanings.

Insects as metaphors for upper-class women

The metaphor of the fly is quite easy to understand. Woolf uses insects to compare Mabel with women of high society. Although, Mabel tries to imagine the guests as "flies, trying to crawl over the edge of the saucer," all seeming identical and with the same intentions, "she could not see them like that… She saw herself like that--she was a fly, but the others were dragonflies, butterflies, beautiful insects" (12). Mabel feels ugly and thus insecure because the cut of her new dress is not appropriate for this fashionable party.

Clothing as a metaphor for gender and class restriction

Mabel hates her chosen dress precisely because it does what she has previously wished it to do: to display her unique identity. She feels that all the guests are thinking, "What a fright she looks! What a hideous new dress!"(13), and even becomes paranoid. When Rose Shaw tells her the dress is "perfectly charming" (14), Mabel is certain that she has derided her. Even when others discuss issues related to their own lives, she imagines they are exchanging secret messages about her appearance. In this context, clothing clearly substitutes social coercions and the ways in which they exercise power and control over Mabel’s personal identity, prompting her to abandon all agency regarding her identity.

In Orlando: A Biography (1928), Woolf’s narrator discusses the changes produced in Orlando when she becomes female, by saying: "there is much to support the view that it is clothes that wear us and not we them; we may make them take the mould of arm or breast, but they mould our hearts, our brains, our tongues to their liking." (15).

In "The New Dress", written four years before the publication of Orlando, we can already see how clothing imposes a new identity from the outside. Social coercions of class and gender expectations launch an attack on her at the party, repressing her individuality, telling her what an ideal woman should look like, transforming both her view of her dress and of herself, leaving her without self-confidence.

The intimate relationship between dress and identity is portrayed through Mabel’s stream-of-consciousness being focused on her anxieties about her clothing consciousness and how her dress operates as a narrative metaphor for her identity, creativity and originality. Her sense of "elegance", which is in opposition to her acknowledgment of the "blunder" of her dress, demonstrates that she is being "disgraced" by other people’s judgment of her. In a male-dominated society, the control of this reflection guarantees the durability of unequal gender relationships. This inequality not only discards Mabel from the space of originality and authenticity, but also hinders her from devaluing the myth of her class and gender inferiority.

Mabel’s unbearable self-consciousness and bodily awareness show us how the body is involved in the social life and controlled by it. Mabel’s new dress acts as substitute for her body; it’s the mould in which she displays her body to the party guests. Her not being happy with her dress, would mean her not being happy in her own skin. One example of the concept of clothing acting as substitute for the body is when Mabel tries on her dress for the first time at the workroom and is thrilled with it, observing that she is "rid of cares and wrinkles"(16). Believing that the wrinkles on her face have vanished with the new dress shows how strong an impact Mabel feels her clothing has on her body itself.

Mirror as a metaphor for the power of sexism and classism

Mirror is a symbolic tool that brings about Mabel’s endless "reflections" of insecurity, embarrassment and agony. It is the symbolic tool of a societal sexism reflecting dot-sized images of women. While listening to Mrs. Holmes, Mabel sees her own reflection in the mirror as a "yellow dot" and that of Mrs. Holman as a "black dot" or a "black button."

"… all the time she could see little bits of her yellow dress in the round looking-glass which made them all the size of boot-buttons or tadpoles; and it was amazing to think how much humiliation and agony and self-loathing and effort and passionate ups and downs of feeling were contained in a thing the size of a three penny bit." (17).

The minimizing mirror tears up Mabel's dress and diminishes her confidence in her expression of style and her creative power to be original, different and unique. It is at this painful moment of self-hatred that we see the mirror as an oppressive device. It is a metaphor for the power of sexism and classism, commanding a proper compliance to society's dominant lookism, and institutionally challenging a woman's control of her body, clothing and appearance. Mabel’s fear, which comes from the mirrors’ amplifying oppressiveness, is in fact an exposition of the women’s struggle with the tyranny of the patriarchy.

The mirror is also framed as a cultural device that speaks concurrently for and against her. It is both amicable (the mirror at Miss Milan’s workroom) and hostile (the ones at the party), threatening Mabel’s emotional well-being.

There is a constant conflict between Mabel’s stream-of consciousness and reality. The mirror intensifies this conflict by its doubling power as it brutally increases her inferiority and fear of encountering "the Other". The identity of "the Other" in the mirror varies and remains ambiguous. Mrs. Colman is a black dot, and Rose Shaw and all the other people there are first seen as flies, and on a second thought as dragonflies and butterflies. This would allow us to locate the root of this corporeal fear in order to identify the mirror's symbolism in the story.

The cause of Mabel’s fear is a form of memory restored in the reflection of the mirror. This memory has two meanings: a reflection of the private sphere of the shortage of economic means drenched in humiliation ; and a reflection of the public threat of the horror of her dress.

Both kinds of reflection make the mirror a complex space in which Mabel’s interaction with it represents a collective feminine experience confronting rigid gender expectations and a denunciation of patriarchy as a whole.

Mabel’s dealing with mirrors also demonstrates both her hostility and attraction towards a reflector that shapes a conflicting identity. She is torn between a loyalty to her real self and a desire to adapt to the gender and class expectations.

"But it was not her fault altogether, after all. It was being one of a family of ten; never having money enough…For all her dreams of living in India, married to some hero …she had failed utterly. She had married Hubert, with his safe, permanent underling's job" (18).

The complicity of the mirror in Mabel’s humiliation acquires a greater meaning. It reveals the way the mirror, this social symbol of women's shared anguish, splits the relationship between her mind and her body. The mirror increases Mabel’s fear by reflecting both her inability to be at the level of others and the numbness of her body or continuously recreating the fear of confronting her inferiority.

The mirror seems to collude with society to censor her appearance. There is a passive acknowledgement of how patriarchal society operates like a belittling mirror, which jeopardizes Mabel’s pursuit of authenticity or originality. So, the story is also a criticism of the compulsion of lookism.

In Mabel’s cosmetic process, the private function of the mind for self-definition in the space of the workplace is in conflict with the beautifying of the body for public evaluation at the party. Social correctness rules; women's looks are instructed by both material and metaphorical mirrors.

Mabel’s looking into the mirror generates a volatile conflict between her clumsy social life and her sophisticated intellectual life. She repeats Shakespearean phrases to reduce her repulsion at facing herself in the mirror, to no avail. "… she issued out into the room, as if spears were thrown at her yellow dress from all sides" (19).

Society comes into force when Mabel's sense of inferiority is aggravated by hearing other guests' apparently sarcastic remarks on her dress. Charles Burt scornfully shouts: "Mabel's got a new dress!" and then: "Rather ruffled?" (20) and laughing at her. Mabel is being scorned because of her association with "newness", because she is "herself, "different" and "original.

At the private mirror, Mabel gets ready to be presentable. However later, the public mirrors at the party determine the notion of presentability for her, and the wish to be presentable makes her see only other guests’ judgment of her. Thus, Mabel’s self-perception is a reflection of a reflection: what she sees is not herself, but a reflection of other people’s opinion of her, implying that people in the party in fact own her image.

*

"The New Dress" is a skillful meditation on the nature of human consciousness and the way we "construct our realities" as well as on the elusive nature of reality itself. Woolf determines this point by showing how divergent are Mabel’s opinions of herself when she views herself first as a "beautiful woman" and then as a "dowdy … old fly". What does this tell us about Mabel’s, and our, comprehension of reality?

*

At the end of the story, Mabel reminisces about occasional "delicious" moments in her life when she was happy and in harmony with everything on earth, and decides to create changes in her life by reading a "helpful" book or listening to a motivational speaker, and leaves the party with these new thoughts.

The message that the narrator sends could be that while women’s clothing frequently substitutes for the limits put on women, it also suggests the possibility of change and opting for new identities. The essential issue for us is not to allow our clothing and its associated social pressures to control our psyche, as it happens to Mabel, but to be able to use clothing in order to actively transform the way we think of ourselves and the way we let others think about us.

From Virgina Wolf to Naomi Wolf

Sixty-four years after Virginia Woolf's "The New Dress" exposes how a patriarchal society decides what is bodily suitable for a woman and what is not, Naomi Wolf, in her book "The Beauty Myth" (1990), maintains that the content of the norm of "beauty" is totally constructed by the patriarchal system in order to reproduce its own power and control.

Wolf states that the patriarchal system has created, and is using, the unreachable model of an "iron-maiden" to chastise women for not being able to conform to it. She criticizes the fashion and beauty industries for exploiting women and asserts that women must not be psychologically and politically denigrated based on their looks through social expectations, advertisements, economic control or legal verdicts, that we must be able to make personal decisions about our appearance without the fear of a penalty.

She rightfully deplores the fact that while women have successfully defied the power structures and overcome so many economic and legal obstacles, we are being bombarded more than ever with images of feminine beauty. Furthermore, there are the mainstream justifications of the pornography, spread of cosmetic surgery as a routine procedure, and the rapid rise of eating disorders, dieting and weight issues. In other words, we witness that while women have more economic power and legal rights than in the past decades, our perception of our appearance seems to have greatly deteriorated.

Notes

(1) Woolf, 1989, P.170 ------ (2) Ibid. ------ (3) Ibid. ------ (4) Ibid., P. 171------ (5) Ibid., P. 174 ------ (6) Ibid., P.175 ------ (7) Ibid., P.172 ------ (8) Ibid. ------ (9) Ibid. ------ (10) bid. ------ (11) Woolf, 1980, P.12 ------ (12) Ibid., P.171 ------ (13) Ibid., P.170 ------ (14) Ibid. P.171 ------ (15) Woolf, 1995 (1928), P. 138 ------ (16) Woolf, 1989, P.172 ------ (17) Ibid., P.174 ------ (18) Ibid., P.175 ------ (19) Ibid., P.173 ------ (20) Ibid.

References

Wolf, Naomi. 1990. The Beauty Myth: How Images of Beauty Are Used Against Women. William Morrow et al.: New York.

Woolf, Virginia. 1989. The New Dress. In The Complete Shorter Fiction of Virginia Woolf. Ed. Susan Dick. Harcourt Inc: San Diego. PP.170-177.

Virginia Woolf.1995 (1928). Orlando: a biography. Hertfordshire, Wordsworth Classics: UK.

The Diary of Virginia Woolf, 1980. vol. 3, 1925-1930. Ed. Anne Olivier and Quentin Bell. Hogarth Press: London.

| Recently by Azadeh Azad | Comments | Date |

|---|---|---|

پیروزی نسرین ستوده پس از ٤٩ روز اعتصاب غذا | 32 | Dec 04, 2012 |

نامه به سازمان عفو بین الملل برای آزادی نسرین ستوده | 1 | Nov 30, 2012 |

مفهوم سازی واژه گونه (۳-٩) | 1 | Nov 27, 2012 |

RECENT COMMENTS

IRANIANS OF THE DAY

| Person | About | Day |

|---|---|---|

| نسرین ستوده: زندانی روز | Dec 04 | |

| Saeed Malekpour: Prisoner of the day | Lawyer says death sentence suspended | Dec 03 |

| Majid Tavakoli: Prisoner of the day | Iterview with mother | Dec 02 |

| احسان نراقی: جامعه شناس و نویسنده ۱۳۰۵-۱۳۹۱ | Dec 02 | |

| Nasrin Sotoudeh: Prisoner of the day | 46 days on hunger strike | Dec 01 |

| Nasrin Sotoudeh: Graffiti | In Barcelona | Nov 30 |

| گوهر عشقی: مادر ستار بهشتی | Nov 30 | |

| Abdollah Momeni: Prisoner of the day | Activist denied leave and family visits for 1.5 years | Nov 30 |

| محمد کلالی: یکی از حمله کنندگان به سفارت ایران در برلین | Nov 29 | |

| Habibollah Golparipour: Prisoner of the day | Kurdish Activist on Death Row | Nov 28 |

Dear Mahvash

by Azadeh Azad on Fri Dec 16, 2011 06:52 PM PSTThanks for reading the review and commenting on it.

Virginia Woolf was a deep-thinker and very much ahead of her time. I recently discovered that the word "masculinist", which is being used in Gender Studies for the last 20 years, was created by her. She was also very playful with words and had her own "lexicon". For instance, in this story, she has used the word "scrolloping" as in "a scrolloping looking-glass". You cannot find this word in any dictionary. After a research, I found out that this word is a combination of the noun

“scroll” (parchment, roll) and the verb “Lollop” (relaxing), and it means

“Expandable portmanteau”, referring to the mirror. Very interesting and amusing!

Cheers,

Azadeh

Virginia Wolf's foot-steps

by Mahvash Shahegh on Fri Dec 16, 2011 06:03 AM PSTI enjoyed your scholarly and well-written and argued article. Virginia Wolf is one of the greatest regarding women issues and feminism. One can see her foot-steps in most of the related feminist topics all the time.

Sometime I ask myself which system exploit women more: Western one or Islamic! I, personally, think in exploiting and degrading women's dignity they are the same; two extremes of an expectrum.

Despite all achievements and progress, women still have a long way to go. Changing perception and getting rid of a historical baggage takes time.

Thanks, Azadeh khanom