به زبان فارسی

PICTORY

LATEST MUSIC

SEARCH

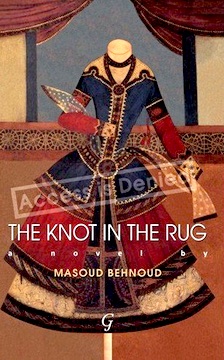

The Knot in the Rug

by elijah

28-Jul-2012

This epic novel encapsulates the massive upheavals of the first half of the twentieth century, including the Second World War and the terrorist attacks of 9/11, from a point of view that the English-speaking readership rarely glimpses.

The book’s heroine, Kahnoum, is born in the courts of Persia’s Qajar Dynasty in 1900, but is forced to leave the comfort of her aristocratic home and flee for Europe during the Constitutional Revolution of 1906. Her teenage years are marked by her struggles, family tragedy and her uncertain future. Ever resourceful, she faces her ordeals with compassion, grace and a childlike sense of humour. The twists and turns in Khanoum’s life make for a compelling read, whilst at the same time shedding light on traditional Persian customs of birth, marriage and death, still followed in modern-day Iran.

The Knot in the Rug will greatly appeal to those who enjoy epic novels, and to those who want to learn more about the upheavals of twentieth century Europe, viewed from a unique perspective.

Masoud Behnoud is a prominent Iranian journalist, historian and writer, whose work has been banned in Iran since Ahmadinejad took power. He has to-date written six books on the contemporary history of Iran. In The Knot in the Rug he expresses pride in his country, beautifully articulating the joyfulness of his people and the richness of their culture.

Chapter 1

W hen she opened her eyes under the blanket it was midnight and, as she had for the past four years, she momentarily forgot where she was. As always, the first thing she thought of was Khanoum. Then, as though someone had switched the light on, she asked herself, ‘What’s Nanaz doing now?’ When Nanaz had

last come to see her she had wondered why she was so happy. ‘Nanaz, are you looking after Mother?’ she had asked. Nanaz had burst out laughing.

‘On the contrary, Khanoum’s looking after me!’

She wanted to open her eyes and talk to Narguess, as they always did whenever one of them was feeling low. The thought of tomorrow, however, had made her restless. This had nothing to do with Narguess so she’d better let her sleep.

‘Close your eyes,’ she told herself. She could think better with her eyes shut and she always felt better when lost in thought. It was Mrs Sediqi, actually, who had taught her that one felt liberated when one had one’s eyes closed; she could then take a trip with whomever she liked and to wherever she fancied.

Narguess said, ‘You have an educated and well-mannered soul but mine is unruly. I can’t keep hold of its hand!’

Narguess is truly a slave to her unruly spirit which never ceases to get her into trouble.

‘Are you awake, Narguess?’

She felt Narguess was awake and so wanted to spend this one last night chatting to her.

‘How can you say that? How could I possibly forget you? You, too, will be released one of these days. I hope you haven’t forgotten what Akram said? Well, if you can’t rely on what she says, then I am not to walk free tomorrow either! But, for now, come and rest your head next to mine so that we don’t wake Mrs Izadi up. Let me tame your soul and you can tell me why you have difficulty sleeping. But let’s not talk about those nights, let’s talk about the future. Do you recall the book that said, “Tomorrow’s beautiful because it’s neither like the past nor like anything else that is old”?

‘What? I didn’t hear what you said; I just felt your breath on my ear. Are you crying? Come on, this is my last night and tomorrow I’ll be free to leave and go to Khanoum, and to Nanaz, who can’t wait to see me. Have you already forgotten what you said to me; that you’d even be happy to stay here in my place so that I could go back to Khanoum? So why did you knit that scarf for her? You’ve never seen her before! Didn’t you promise you’d come and stay with us when you walk free? With us, Khanoum, Nanaz and me? Perhaps Akram wasn’t right after all and I shan’t be released tomorrow. Are you listening to me or are you asleep?

‘Listen to me, you ninny! You can give me your restless mind to take with me. I’ll set your diary free as well, but I shan’t take my books and notes. Take them with you when you leave this place. So now, please sing for me ...

O little sparrow,

You’ll be a ball when it snows;

You’ll be wet when it rains ...

‘When you come we’ll shut ourselves in your room and then we’ll sing freely and out loud, like the other night when you were ranting for no reason. I want Khanoum and Nanaz to hear your voice. Will you promise to read something by Forough1 to them?

... I’ll plant my hands and they’ll grow ...

‘Narguess, are you sleeping? Lucky you ...’

When she got up the next day, she was busy folding the blanket when she saw Narguess’s face, but it was difficult to tell whether she had heard her the previous night. Everyone began to wake up to Aqdas Khanoum’s loud voice. Akram was also there and, as usual, she was calling them to go to the washrooms. They both looked to see whether they could read anything in her expression that hinted at the release of prisoner number 820. Her eyes met Maryam’s and she beamed. As soon as Maryam had finished washing her face she said, ‘I hope you’re not suddenly going to pounce on Khanoum!’ – something she had repeated over and over again.

She kept to herself for the next half-hour while the other twelve inhabitants of prison cell number 99 were chatting away. Akram nodded, and when Maryam had finished kissing everyone goodbye she took her bag and quickened her pace as she followed Akram to the guard’s room. Akram answered a couple of questions for her. She then signed a bundle of papers and heard a young man’s voice asking her not to ‘remember him for the bad times behind bars’. She then heard Akram’s last words reminding her to help Narguess out of prison as soon as she could.

‘Will you go to Faramarz?’

No, she hadn’t forgotten; Maryam was aware that Faramarz was Akram’s only son who was buried in the martyrs’ corner in the public cemetery.

When they passed through the last exit Akram patted her on the back. They were both tearful. They had not been referring to one another as prisoner and guard for some time now. She managed the remaining formalities without Akram’s help and an hour later the large gates finally opened and Maryam swung one leg over the iron bar surreptitiously separating her from the outside. As she lifted her other foot she was seized with fear; there was daylight and noise on the other side. She was relieved that

no one had come to pick her up. She felt so lonely, loneliness far more profound than anything she had ever experienced.

For a moment, she felt that everyone around her was also a fellow prisoner. The cars driving past and the woman carrying a plastic bag took no notice of her as she stepped into their world. Maryam began to walk uphill when she caught sight of the familiar figure of the young man in the tower. Her shoes felt loose but they made her feel good. A man brought his Paykaan to a halt; the most popular car assembled in Iran, the old Hillman Hunter; and she heard the military anthem blaring from its radio, which was duly interrupted by the narrator, who gave a passionate monologue about the ‘Godless’ army under siege by brave Islamic forces. The driver said something Maryam couldn’t hear. She caught sight of a telephone booth and went to the corner shop across the road. After obtaining a coin from the shopkeeper, she started to dial ...

She closed her eyes and let ‘Allo, Allo’ travel through her ears. She could vaguely hear a young man talking to the shopkeeper about a couple of air strikes somewhere in mid-town. She was about to pass on the news when her eyes suddenly encountered those of a man who was smiling broadly at her. She put the receiver down and began to walk briskly uphill until she reached the market. There was a memorial ornamental kiosk right outside the mosque, still in Evin, near the notorious prison. The loudspeakers began transmitting the chanting of the verses of the Holy Qur’an when she sensed the smiling man was still following her, but by now she had reached the mosque. She sat on the carpeted floor watching a group of women busy wrapping packs of dates intended for the war front. She was soon so absorbed in helping the women that she didn’t even notice noon arrive. After a while the women stood up to get ready for prayers, but she didn’t move. When lunch was laid out on a cloth over the carpets, someone offered her a bowl of broth. An hour later she was resting her head against a pillar, and soon she was unrecognisable, completely covered in her chador. In the quiet of her cover, she was once again on her own, and her memory could lead her back to New Jersey. There she was, in her graduation gown sitting in the front row, on the lawn. Her mother, Khanoum, looking elegant and distinguished, was chatting to an American gentleman, one of the many parents. She was delighted her mother had managed to come all the way from Iran to attend her graduation despite the complications. Clad in a blue silk dress and a hat, she was a princess who had captivated Nader, her beau, and everyone else. She found herself encountering her mother’s adoring gaze. With a rolled diploma in her hand she was now standing between Khanoum and Nader.

As she leaned against the pillar in the mosque, Maryam suddenly remembered the mosque in New Jersey: she was marrying Nader, and her mother was giving him a pocketwatch, an antique on a gold chain. Then came the necklace; she knew this was her mother’s own wedding memento that she had been keeping safe for such a day. She had seen the same necklace in a picture of a young woman dressed in early nineteenth-century fashion, wearing a hat and holding an umbrella. Soon she remembered Nanaz’s first screams in a New Jersey hospital, the sound of life, and ... she fell asleep. They were standing inside the airport, Nanaz and her. She found herself explaining to the little girl.

‘Nana, we’re going to Iran; to Khanoum my love, and to Tehran, city of Revolution, city of “Down with the Shah” and “God is Great, Allah Akbar” shouted from the rooftops.’

There she was, Khanoum, sitting on the veranda listening to her radio, beaming with happiness; those were the days of flowers and tears.

And now she was pleading with her husband.

‘Please come with us Nader! We’ll never see such days again. I know what you’re thinking but it’s not as though I’m mad or vengeful even. We’re not going over just to see the fall; this is not just a fall, Nader, this is history in the making, please come! We shan’t be alone in the house; there’ll be Manssoureh and her family, Ali Akbar and his children, a full and lively house.’

The curfew, the Shah’s escape and the joyful tears of Khanoum, her darling mother; the social nights when Khanoum listened to the radio; the days of demonstrations and the fear of a coup d’état; the siege of the garrisons; Hussein and Hassan, Ali Akbar’s sons, and the weapons; the young people meeting in the basement and planning the next day’s moves; the day happiness burst out; spring in the middle of winter ... The victory of the Revolution!

‘I’m sorry Nader, Mother doesn’t wish to come over any more, and we’ll stay here as well. Why not come and join us? Mother’s been waiting for this day for fifty years!’

Maryam suddenly felt short of breath under her chador and she began to sense a sharp pain starting in the back of her head and moving down her spine. She lifted her head so that her eyes were no longer covered with the chador and she could see the ceiling of the mosque and the light pouring through the window onto the pile of donations. She knew she would soon have difficulty breathing.

‘Oh Narguess,’ she sighed, and then her voice petered out; she was unconscious.

An anxious-looking woman went to her, and began to wipe her moist brow with the corner of her scarf and brought a glass up to her mouth.

Maryam managed to hold the glass, and returned the woman’s kindness with a faint smile and then propped herself up.

‘Where am I?’ she asked but it didn’t take her long to remember.

Someone in the crowd said, ‘Give her some halva, she looks so pale!’

The morsel of the sweet paste taken with some flat bread tasted familiar; the flat golden long triangle of bread that Muhammad Ali used to buy every morning.

Picking up the telephone receiver, she said, ‘Nanaz, is that you? I’ll be home soon ... don’t say anything to Khanoum.’

‘Where are you?’

‘Not far at all!’

The radio in the car that she managed to hail, as one did when

there were no taxis, was playing military anthems. She sat neatly in the backseat, just as she had done four years ago, but going then in the opposite direction; to prison, to Evin.

‘My goodness, you’ve grown so much, Nanaz!’

She then turned to Mr Ali Akbar and said, ‘I owe you a great deal; I’m not sure what would’ve happened without you. Where are the boys, Hussein and Hassan?’ But the man was quiet; she had to find the answers for herself.

She was talking to them, Nanaz and Ali Akbar, in the alleyway. The road was named ‘Hussein’ after the shy one who dropped his gaze when she left, biting his lower lip and kicking the edge of the flowerbed with his boot.

‘I don’t really need a bath, Nanaz.’

But the smell of lavender, her favourite aroma, had filled the air in the bathroom and she could hear Shirley Bassey’s voice seeping through the steam. She spotted a few grey strands when she looked in the mirror, where Nanaz had traced out ‘I NEED U’ in the steam. She suddenly noticed her mother; Khanoum was standing in the doorframe, leaning on the same old walking-stick. She had a brown and beige scarf on her head, just as she did when she was watching her leave through the window.

‘Naughty Khanoum!’

Maryam had never heard anyone refer to her mother in that manner, which made her glare at Nanaz. But then she heard her mother say in return: ‘Go away, you little rascal!’

She went forward into her mother’s outstretched arms and, as she did, the 1623 days’ captivity, Akram and Narguess, were all forgotten. Nanaz was supporting Khanoum’s body from behind, by placing her forehead against her spine; her walking-stick was shaking. Once again they were together, inseparable – and she had yet to find out what had passed between Nanaz and Khanoum in the past four years.

Early on she noticed that her daughter was guarding her mother like some Old Master painting, and she sensed something in their eyes that was sweet, familiar yet strange. She’d never come to feel as close to her mother, but in the days that followed she discovered that in Khanoum’s care Nanaz had grown into a strong young woman. She was no longer an insecure little waif of a girl, but a rock on which one could lean, or a large tree laden with fruit, spreading its wonderful shade in the heat.

Barely three days out but she was already thinking of all the things she had to do. She went to Shiraz to visit her cellmate’s sister and brother, Narguess’s siblings. She also accompanied Akram to the martyrs’ corner in the public cemetery to visit the spot where Faramarz, Akram’s beloved son, was lying. She had also not forgotten to visit another cellmate’s sick, blind mother as well, and ...

One evening they were sitting in the basement, a safe haven where her mother had everything she needed. Next to her antique bed was a desk with an old typewriter. There was also a tape recorder that had been brought down from the floor above, as well as a box of tapes. There was another bed nearby where Nanaz slept so that she could attend to her grandmother should she feel unwell during the night. There was also a framed photograph of Nader and herself.

‘You don’t seem to have had such a bad time!’ Maryam had hardly noticed the Shirazi accent she’d picked up.

‘I guess Narguess must be speaking English with a downtown New Jersey accent!’ Nanaz teased. Their laughter filled the room.

‘By the way,’ Maryam said, ‘she’s going to walk free one of these days and you’ll see for yourself!’

And that wasn’t news. Maryam’s daily visits to the public prosecutor and the preparations in the room upstairs were all testament to the imminent arrival of their guest, someone who was going to stay some time.

And so she did. In just under a month, after Khanoum had gone into intensive care, Narguess joined them, and they tried their best not to worry her with their concerns for Khanoum. Once the visit to Shiraz was out of the way, Narguess went to the hospital with them every morning. Khanoum was sleeping peacefully surrounded by tubes and wires. Narguess and Maryam had repeatedly had to pull Nanaz away from the incubator; she would rest her forehead against the walls of the corridors at the hospital and mutter something, as though she was reading a prayer or calling ‘Khanoum’ over and over again.

‘Don’t go, my dear Khanoum!’

Her voice was far more upsetting than hearing someone sob. And she went on, until someone disconnected all the tubes and wires, and covered her grandmother with a white sheet. It was as though she had lingered on just long enough to hand Nanaz over to her own mother.

Nanaz had promised to be quiet and not to disturb the other patients, so she was allowed to follow the head nurse towards the body of her grandmother, lift the sheet, and stare at her peaceful face. She pecked on her forehead and said: ‘I promise you!’

She didn’t weep any more.

***

Our story is about Khanoum, the story of a life she had told to no one; a story that she had narrated and Nanaz had recorded during the dark nights when Iraq sent its missiles to Tehran. It was a story that inspired the little girl to believe in the power of the human spirit. She had come to learn that, although encased in a fragile body, humanity could endure pain with the strength of a rock.

Khanoum had told her story in such a way that the little girl had fully understood its magnitude. You, too, are about to hear it in the memory of a woman who was truly a khanoum – a lady. She was never called by any other name, nor was there one that better suited her character.

She is buried under a black slab in the middle of the Emamzadeh Abdullah cemetery in Tehran. Written on the slab is, ‘Khanoum, born 5th April 1900, died 5th December 1986’, and here is the tale just as she narrated it.

| Recently by elijah | Comments | Date |

|---|---|---|

| The Gaze of the Gazelle | 2 | Oct 22, 2011 |

| "I am Cyrus" by renowned film director Alex Jovy | 1 | May 09, 2011 |

| Paulo Coelho titles in Persian | 1 | Jan 14, 2011 |

RECENT COMMENTS

IRANIANS OF THE DAY

| Person | About | Day |

|---|---|---|

| نسرین ستوده: زندانی روز | Dec 04 | |

| Saeed Malekpour: Prisoner of the day | Lawyer says death sentence suspended | Dec 03 |

| Majid Tavakoli: Prisoner of the day | Iterview with mother | Dec 02 |

| احسان نراقی: جامعه شناس و نویسنده ۱۳۰۵-۱۳۹۱ | Dec 02 | |

| Nasrin Sotoudeh: Prisoner of the day | 46 days on hunger strike | Dec 01 |

| Nasrin Sotoudeh: Graffiti | In Barcelona | Nov 30 |

| گوهر عشقی: مادر ستار بهشتی | Nov 30 | |

| Abdollah Momeni: Prisoner of the day | Activist denied leave and family visits for 1.5 years | Nov 30 |

| محمد کلالی: یکی از حمله کنندگان به سفارت ایران در برلین | Nov 29 | |

| Habibollah Golparipour: Prisoner of the day | Kurdish Activist on Death Row | Nov 28 |