به زبان فارسی

PICTORY

LATEST MUSIC

SEARCH

The Butcher

by Ari Siletz

08-Jul-2009

The call to noon prayer beats down from the sun. A laborer mutters his devotion in the scant shade of a sapling.

Guide us along the straight path

The path of those You have favored

Not of those with whom You are angry

Not of those who are lost.

Enough playing and sightseeing at the marketplace. Time to go home for lunch. I had spent the day watching the grape flies at the fruit seller's shade. They float silently in the fragrant air, their wings blurred around them like halos. They read your mind. Try to grab one and it has already drifted serenely out of the way. No hurry, no panic. They know the future.

On the short walk home, the sun is already bleaching memories of the fruit seller's paradise. Guide us along the straight path ...Why do we need guiding along the straight path? I wonder.

I reach the house, but the gate is locked. I don't feel like knocking; there is an easier way. The neighbors are building a wall and there are piles of bricks everywhere. After many trips back and forth I have enough bricks to make a step stool with which to climb the wall into the house. My arms are scraped pink by the effort. I sneak to the kitchen and try to startle my mother.

"You better go put those bricks back before the neighbor sees them," she says.

The next day I pass by the fruit seller's and go straight to the cobbler's tiny shop. A pair of my mother's shoes needs mending. The cobbler flashes a "two" with his fingers and goes back to the shoe at hand. His hair and beard look just like the bristles he uses on the shoes.

"I will wait for them here," I say as I pull up a stool. He does not hear me. The walls are covered with unfinished shoes waiting to be soled. They look like faces with their mouths wide open.

"They are shouting at each other," I say, pointing to the walls. The cobbler cannot hear them; he is deaf-mute. He emphatically flashes two fingers again. Come back in two hours. So I walk next door to the butcher's shop to look at the ghastly picture on his window and try to figure out what it means. I hesitate to ask him. Some things are better left alone.

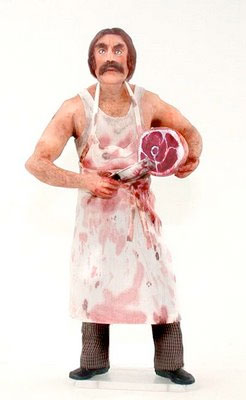

The butcher is a decent man. He has to be, for he is entrusted with doing all our killing. Even though we pass on the act, we are still responsible for the deaths we cause. The killing must be done mercifully and according to the rules of God. The killer must be pure of heart and without malice for the world.

Our butcher was a man of great physical and moral strength. My mother said he reminded her of the legendary champion, Rostam. Rostam was so strong that he asked God to take away some of his strength so that he would not make potholes wherever he walked.

The butcher was very big. Every time he brought down the cleaver, I feared he might split the butcher's block. His burly hands carried the power of life and death. The carcasses hanging on the hooks and the smell of raw meat testified to this. Above the scales was a larger-than-life picture of the first Shiite imam, Ali, who supervised this Judgment-Day atmosphere with a stem but benevolent presence. Across Ali's lap lay his undefeated sword, Zulfaghar.

But the true object of my terror was the picture in the shop window. A man was chopping off his own arm with a cleaver. The artwork was eerie, as the man's face had no expression-he stared blankly at the viewer while the blood ran out. This was the butcher's logo. Underneath it the most common name for a butcher shop was beautifully calligraphed: Javanmard (man of integrity).

I had asked my mother what the mutilation signified. She had said it was a traditional symbol attesting the butcher's honesty, but she could not explain further.

"Is the butcher honest?" I asked.

"Yes, he is very honest. We never have to worry about spoiled meat or bad prices."

"He would rather chop off his arm than be dishonest? Is that what his sign means?"

"Yes."

"What about other shopkeepers? What have they vowed to do in case they are dishonest?"

"I don't know."

"What about the cobbler? Did he do something dishonest? Is that what happened to him?"

"I don't know."

"Is that why people kill themselves? Because they have been very dishonest?"

"Look, it is just a picture. It's not worth having nightmares over. Next time you are there, you can ask him what it means."

I did not ask him about it until I was forced to by my conscience.

One day my mother sent me out to buy half a kilo of ground meat. She told me to tell the butcher that she wanted it without any fat. She knew it would be more expensive and gave me extra money to cover it. I got to the butcher shop at the busiest time of the day. One good thing about the butcher was that he, unlike other shopkeepers, helped the customers on a first-come, first-served basis. Status had no meaning for him and he could not be bribed. People knew this about him and respected it. When he asked whose turn it was, instead of the usual elbowing and jostling, he got a unanimous answer from the crowd. People do not lie to an honest man.

This gave great meaning to the picture of Ali above the scales. Ali, the Prophet's son-in law and one-man army, is known for his uncompromising idealism. His guileless methods were interpreted as lack of political wisdom, and he was passed over three times for succession to Mohammad. When he did finally become caliph, he became an easy target for the assassin as he, like the Prophet, refused bodyguards for himself. Shiites regard him as the true successor to Mohammad and disregard the three caliphs that came before him.

When my turn came up, I asked for half a kilo of ground meat with no fat. The butcher sliced off some meat from a carcass and ground it. Then he wrapped it in wax paper and wrapped that in someone's homework. Sometimes he used newspapers, but because of the Iranian habit of forcing students to copy volumes of text for homework, old notebook paper was as common as newsprint. He gave me the meat and I gave him the money and started to walk out, but he called me back and gave me some change. This was free money; my mother had not expected change. I took the money and immediately spent it on candy.

When I went home, I did not tell her that she had given me too much money. I worried that she would know I had spent the change on sweets and that she would yell at me for it. Around noontime my mother called me into the kitchen. She asked me if I had told the butcher to put no fat in the meat. I said I had told him.

"I thought he was an honest man. He gave you meat with fat and charged you the higher price," she said sadly.

Now I knew where the extra money came from. In the heat of business he had forgotten about the "no fat" and had given me regular ground meat. But he had not charged me the higher price.

"We will go there now and straighten this out with him," she said sternly.

I thought about confessing, but I deluded myself into thinking the change had nothing to do with it. After all, he made the mistake. How much change had he given me anyway? Or maybe my mother was wrong about the quality of the meat. I was just a victim of the butcher's and my mother's stupidity.

It was still noontime as we set off to straighten out the butcher. The call to prayer was being sung. Across the neighborhood devout supplicants beseeched their maker.

Guide us along the straight path

The path of those You have favored

Not of those with whom You are angry

Not of those who are lost.

I was certainly lost, fighting the delusion like a drug, now dispelling it, now overwhelmed by it. When things were clear, I could see that I had done nothing wrong except fail to get permission to buy candy. The butcher made a mistake, I did not know about it, and I bought unauthorized sugar. All I had to do was tell my mother and no crime would have been committed. The real crime was still a few minutes in the future, when I would endanger the reputation and livelihood of an honest man. I still had time to avert that.

Guide us along the straight path...

When delusion reigned, I felt I had committed a grave, irreversible sin that, paradoxically, others should be blamed for. The straight path was so simple, so forgiving; the other was harsh and muddled. How much more guidance did I need? The prayer did not say "chain us to the straight path." When we reached the shop, the butcher was cleaning the surfaces in preparation for lunch. He usually gathered with the cobbler and the fruit seller in front of the cobbler's shop. They spread their lunch cloth and ate a meal of bread and meat soup. In accordance with tradition, passersby were invited to join them, and in accordance with tradition, the invitation was declined with much apology and gratitude.

My mother told him that when she finished frying the meat, there was too much fat left over and she thought the wrong kind of meat had been sold. She asked if he remembered selling me the meat. The butcher was unclear. He remembered having to call me back to give me some change, but he was too busy at the time to remember more. My mother said that no change would have been involved as she had given me the exact change. This confused the butcher and he decided that he did not remember the incident at all. His changing of his recollection added to my mother's suspicions. Meanwhile, Ali was glowering at me from the top of the scales, his Zulfaghar ready to strike. My face was hot and my fingers felt numb.

Finally, the butcher, who was not one to argue in the absence of evidence, ground the right amount of the right kind of meat, wrapped it in wax paper, wrapped that in someone's homework, and gave it to my mother. She offered to pay for it, but the butcher refused to accept the money and apologized for making the mistake. When we left, he was taking apart the meat grinder in order to clean it again.

On the way back I felt sleepy. My mother asked if I was all right.

"I'm fine," I said weakly.

"Your father will be home in a few more days," she reassured.

"Mother, do you think the butcher was dishonest?" I asked.

"No, I think he really made a mistake."

"How do you know that?"

"Because he gave us the new meat so willingly. If he were a greedy man, he would not have done that. He probably feels very bad."

A terrible thought occurred to me. "Bad enough to chop off his own arm?" I asked urgently.

"I don't think so," she said.

But I was not convinced. She did not know what awful things could happen off the straight path. "I have to go back," I said as I started to run.

"Where are you going, you crazy boy?"

"I have to ask him about the picture," I yelled.

"Ask him later, now is not the time.... " She gave up. I was already a whorl of dust.

I was panting and swallowing when I saw the butcher. He was having lunch with the cobbler and the fruit seller. What did I want now?

"Please, help yourself," said the butcher, inviting me to the spread. I just stood for a while.

"Why do you have a picture of the man chopping off his arm?" I finally asked. The cobbler was tapping the fruit seller on the back, asking what was going on. The fruit seller indicated a chopping motion over his own arm and pointed toward the butcher shop. The cobbler smiled and repeated the fruit seller's motions.

"That is the Javanmard," the butcher said. "He cheated Ali."

"Why?" I asked.

"Even when he was caliph, Ali did not believe in servants. One day a man came to the butcher's shop and bought some meat. The butcher put his thumb on the scale and so gave him less meat. Later he found out that the customer was Ali himself. The butcher was so distraught and ashamed that he got rid of the guilty thumb along with the arm," he said.

I was greatly relieved. One did not mutilate oneself for committing a wrong against just anybody. It had to be someone of Ali's stature. Our butcher was safe even if he was to blame himself for the mistake. But I had to be absolutely sure.

"So if one were to cheat someone not as holy as Ali, one would not have to feel so bad?" I asked. Looking back, I see that he interpreted this as a criticism of the moral of the parable. He was transfixed in thought for a long time. The cobbler was tapping the fruit seller again, but the fruit seller could not find the correct gestures; he kept shrugging irritably.

The butcher finally came to life again. "Ali was good at reminding us of the difference between good and bad," he explained.

I was glad I was not so gifted.

"Would he have killed the butcher with Zulfaghar?" I asked.

"No, in fact I think once he found out what the butcher had done, he went to him and healed the arm completely," he said, displaying his arms. I looked carefully at his arms, but there was not even a trace of an injury. "A miracle," he explained.

The fruit seller was able to translate this and the cobbler agreed vigorously. He had something to add to the story, but we could not understand him.

During lunch I told my mother the butcher's story.

"Now why couldn't this wait until tomorrow?" she asked, collecting the dishes.

"Mother?"

"Yes?"

"If I were to get some change and not bring it back, what would you do?"

"Did you get change and not bring it back?" She smelled a guilty conscience.

"No, I was just wondering."

"It depends on what I had sent you to buy," she said deviously.

"Like meat for instance."

She pondered this while she did the dishes. When she was done, she donned her chador and asked me to put on my shoes.

"Where are we going?" I wondered.

"To the butcher's," she said curtly. "You are going to apologize and give him the money we owe him."

"It was his mistake," I protested guiltily.

"And you stood there all that time, under Ali's eyes, and watched him grind us the new meat without saying anything."

I followed her dolorously out the gate. I could tell she was upset because she was walking fast and did not care if her chador blew around. But halfway there she changed her mind and with a swish of her chador ordered me to follow her back home.

"Why are we going back, Mother?"

"If this gets out, they will never trust you at the marketplace again," she said angrily.

"So we are not going to apologize?"

"Of course you will apologize. You are going to give him your summer homework so he can wrap his meat in it."

The summer homework filled two whole notebooks. The school had made us copy the entire second grade text. Completing it had been a torturous task and a major accomplishment. My mother had patiently encouraged me to get it out of the way early in the vacation so that it would not loom over me all summer.

"What will I tell the teacher?" I begged.

"You will either do the homework again or face whatever you get for not having it. Or maybe instead of the homework you can show her the composition you are going to write."

"We did not have to write any compositions," I whined.

"You are going to write one explaining why you don't have your homework."

So, for the fourth time that day I went to the butcher shop. It was still quiet at the marketplace; the butcher was taking a nap. He woke up to my shuffling and chuckled groggily when he saw me.

"I was looking for you in the skies but I find you on earth (long time no see)," he said.

I gave him my notebooks and told him that my mother said he could wrap meat in them. He thanked my mother and apologized again for the mistake. My mother had told me not to discuss that with him, so I left quickly.

Within a few days, scraps of my homework, wrapped around chunks of lamb, found their way into kitchens across the neighborhood.

I opted for writing the composition explaining the publication of my homework. My mother signed it. The teacher accepted it enthusiastically, and while other students were writing, "How I spent my summer vacation," I was permitted to memorize the opening verses of the Koran. I had heard it many times before and knew the meaning, but I did not have it memorized. It goes:

Guide us along the straight path

The path of those You have favored...

A few summers later, the butcher became involved in the uprising against the Shah. He tacked a small picture of Khomeini next to Ali and Zulfaghar and would not take it down. His customers, including my mother, urged him not to be so foolish.

"Was Ali foolish to refuse bodyguards?" he asked.

"You are not Ali, you are just a butcher. Khomeini is gone, exiled. At least hide his picture behind Ali's picture."

When he disappeared, we all worried that he would never come back. But a few days later, he opened his shop again and, as far as I know, never hid anything anywhere.

***********

Khomeini lost his first battle with the Shah, but he came back fifteen years later to destroy the monarchy. He was perceived by most Iranians to be a man of unrelenting integrity, much like how I remember the butcher. It was easy to believe that under Khomeini's leadership Iran would be cleansed of its corruptions. The greedy and the dishonest would no longer have the advantage over hardworking citizens grateful to God for their daily bread. Khomeini's refusal to compromise with what he thought to be evil eliminated the riddles of our conscience. The line between Good and Evil became as sharp as the slice of a sword. And so the blade promised to establish the laws of Heaven on the land. How many incarnations of Hell have been conjured by those that would live in Heaven?

(From The Mullah With No Legs and Other Stories, by Ari Siletz)

| Recently by Ari Siletz | Comments | Date |

|---|---|---|

چرا مصدق آسوده نمی خوابد. | 8 | Aug 17, 2012 |

| This blog makes me a plagarist | 2 | Aug 16, 2012 |

| Double standards outside the boxing ring | 6 | Aug 12, 2012 |

RECENT COMMENTS

IRANIANS OF THE DAY

| Person | About | Day |

|---|---|---|

| نسرین ستوده: زندانی روز | Dec 04 | |

| Saeed Malekpour: Prisoner of the day | Lawyer says death sentence suspended | Dec 03 |

| Majid Tavakoli: Prisoner of the day | Iterview with mother | Dec 02 |

| احسان نراقی: جامعه شناس و نویسنده ۱۳۰۵-۱۳۹۱ | Dec 02 | |

| Nasrin Sotoudeh: Prisoner of the day | 46 days on hunger strike | Dec 01 |

| Nasrin Sotoudeh: Graffiti | In Barcelona | Nov 30 |

| گوهر عشقی: مادر ستار بهشتی | Nov 30 | |

| Abdollah Momeni: Prisoner of the day | Activist denied leave and family visits for 1.5 years | Nov 30 |

| محمد کلالی: یکی از حمله کنندگان به سفارت ایران در برلین | Nov 29 | |

| Habibollah Golparipour: Prisoner of the day | Kurdish Activist on Death Row | Nov 28 |

Imagination!

by Mehman on Mon Jul 13, 2009 11:18 PM PDT“For example, say I have a lot of feelings about the Iran-Iraq war and want to write a novel about it. But I've never been a soldier. Should my narrator be someone who watched the war from the sidelines (as I did) letting the story happen from the persepective of an observer. Or should I risk sending my narrator to war, even though my experience of the war is vicarious? “

Dear Ari,

While studying literature, I asked the same question from my professor about a decade ago. Can a fiction author write about experiences he/she never has had in his/her life?

The answer was positive. Many great writers have done that. Then he cited many samples from great writers, which I do not recollect now.

‘imagination’ is the key to the writer’s supplement for the experiences he lacks but towards which he has an inclination to explore.

Great writers are endowed with the gift of magical imagination. Some writers describe extraordinarily well the places or events they have never experimented in real life!

And in our days this task has been made easier by the magical power of internet through which a writer can virtually visit places he has never actually visited or vicariously experiment the actions he has never taken part in!

Yes, internet resources plus other library documents and first hand narration from people who have actually accomplished those tasks provide a magical source for the writer with great imagination (like you).

After gathering the necessary second hand experiments the choice of viewpoint is simply the writer’s choice (first person, third person limited or the omniscient vps).

Topoi

by Ari Siletz on Sat Jul 11, 2009 02:27 PM PDTInteresting literary debate. As you are both writers, let me ask to what extent does your choice of narrator depend on where in your memory you find the most emotional content, as compared with the mechanics of your narrator having a credible perspective? For example, say I have a lot of feelings about the Iran-Iraq war and want to write a novel about it. But I've never been a soldier. Should my narrator be someone who watched the war from the sidelines (as I did) letting the story happen from the persepective of an observer. Or should I risk sending my narrator to war, even though my experience of the war is vicarious?

gitdoun

by Ari Siletz on Sat Jul 11, 2009 01:37 PM PDTvarjavand

by Ari Siletz on Sat Jul 11, 2009 01:31 PM PDTAhmed

by Ari Siletz on Sat Jul 11, 2009 01:26 PM PDTi agree Ari

by gitdoun ver.2.0 on Sat Jul 11, 2009 01:07 PM PDTi agree that khomeini and the notion of compromise is as contradictory as fire and ice. or land and sky. it's the end of the premise i have trouble following.

"Khomeini's refusal to compromise with what he thought to be evil eliminated the riddles of our conscience."

i think that statement is valid and is applicable to a particular slice of iranian society. And that of course would be the radical/extremist iranian shias that looked at Khomeini as God's Messiah. I don't think it rings true to mainstream iranians or mainstream iranian shias as of 2009.

First Person vp Plus Limited Omnisciensce in DJN

by Mehman on Sat Jul 11, 2009 01:27 PM PDT"...not by virtue of any significance the narrator has, but by how masterfully Pezeshkzad has written and woven the story."

I gracefully object to the above statement. It is an unavoidable circle: How Pezeshkzad masterfully weaves the story is directly related to how masterfully he chooses a narrator and the way that narrator recounts the story. Narrator is one of the most crucial elements (may be the most important element) in story telling and Dai jan's Napoleon's success depends partially on the 14 year-old first person's narrating point of view that Pezeshkzad has chosen.

It should be noted that in a novel (as opposed to a short story) it is very hard for the writer to relate the whole set of events from the point of view of a first person narrator (known as the persona) because of the limits the first person has in knowing every details of events and characters.

Hence, in a novel the writer often switches between several viewpoints allowing more details to be revealed to the reader. In Daei Jan Napoleon too, the narration leaps often from first person to "limited omniscience" where the 14 year old reveals his own thoughts while at the same time presenting other characters and events externally.

The difference between Limited Omniscience and the Omniscient point of view is that in the former the author reveals the thoughts of a single character (like the 14 year old in DJN) while all other characters are represented externally, whereas in the latter the author is free to enter the minds and lives of each and every character and render them to the reader as an all-knowing god.

Ari, Your storytelling

by varjavand on Sat Jul 11, 2009 07:31 AM PDTAri,

Your storytelling ability is masterful. Have you thought of playwriting?

Reza

The narrator is the writer

by Nazy Kaviani on Fri Jul 10, 2009 11:58 PM PDTIn Iraj Pezeshkzad's unforgettable book, Daei Jan Napoleon, the story narrator is Saeed, a 14 year-old boy on the verge of his first love. The book, with its multiple and colorful cast of characters, is a masterpiece of Persian storytelling. I doubt anyone ever questioned the narrator's age or experience when reading the complex and entertaining tale. The narrator's voice is merely a window from which the story starts and unravels and develops. Beyond this window, the narrator's perceived knowledge and wisdom become somewhat trivial to the whole story. Regardless of the defined characteristics of the narrator, readers will always know and remember that an expert hand wrote the story, and not the narrator.

Here is an excerpt of Daei Jan Napolen, translated as "My Uncle Napoleon" by Dick Davis. You can read the rest of this excerpt here. Have you ever heard of anybody saying that they were perplexed by how Saeed, the 14-year-old boy could know so much about life, love, lust, and politics? The book and the film series based on it have gone on to become one of the most important and effective icons of contemporary Iranian literature and storytelling, not by virtue of any significance the narrator has, but by how masterfully Pezeshkzad has written and woven the story.

Mash Qasem calmly answered his question, "M'dear she wanted to cut his privates off."

Asadollah Mirza laughed and said, "Well, he's brought this on himself . . .

'Someone was chopping the branch off a tree

The lord looked in the garden and happened to see . . .'"

Dear Uncle Napoleon bawled, "Sir, that's enough!"

Then, with a very serious face, and still holding out his cloak as a curtain between Dustali Khan and the women, he said, "Speak properly, Dustali! How is it she wanted to cut it off? Why are you talking such nonsense?"

Dustali Khan, who was still clutching his groin with both hands, wailed, "I saw it myself . . . she'd brought a kitchen knife into the bed . . . she'd got hold of it to cut it . . . I felt the chill of the knife!"

"But why? Had she gone crazy? Had she . . . ?"

"She'd been nagging me all evening . . . she didn't come to your mourning ceremony . . . she said that she'd heard from one of her relatives that I was going with some young woman . . . God damn all such relatives . . . they're all murderers . . . God, if I'd jumped a moment later she'd have cut the whole lot off."

In a choked voice Dear Uncle Napoleon said, "Aha! I understand!"

We all became aware of him. He ground his teeth in fury. In a voice shaking with anger he added, "I know which filthy wretch has done this . . . that fellow who wants to destroy the honor of our family . . . who's made a plot against the honor of our family."

It was very clear that by "that fellow" he meant my father.

Asadollah Mirza, who was trying to be serious, said in an apparently concerned voice, "Well, was any of it cut off?"

Dear Uncle Napoleon ignored everyone's laughter and said through gritted teeth, "I'll destroy him . . . the honor of our family is no joke."

At this moment Shamsali Mirza assumed the extremely serious face of a judge, raised his hands, and said, "Do not rush to judgment . . . first the investigation, then the verdict. Mr. Dustali Khan, please answer my questions carefully and honestly."

The presumed victim of the attack was still lying helplessly on the floor with his hands clutched against his groin. Shamsali Mirza pulled a chair forward and sat down to begin his cross-examination, but uncle colonel interrupted, "Your honor, leave it for tomorrow, this poor devil's been so terrified he hasn't the strength to speak."

Great story telling Dear Ari

by Ahmed from Bahrain on Fri Jul 10, 2009 09:17 PM PDTI was so absorbed into it.

When I was a child my mother used to put us to sleep often by telling us fairytales, mostly from the Persian culture even though she was illiterate.

She could recite Persian poetry by heart, especially from Baba Tahir, as somehow the accent is close to Fars where most Bahraini Persians come from. With TV story telling has become almost extinct.

Just turned sixty but you took me right back to my childhood. People like you are worth their weight in gold.

Bravo. I must get a copy of your book.

Ahmed from Bahrain

Thanks Mehman

by Ari Siletz on Fri Jul 10, 2009 06:27 PM PDTIRANdokht

by Ari Siletz on Fri Jul 10, 2009 01:31 PM PDT"Then I

thought a minute, and says to myself, hold on; s'pose you'd a done right

and give Jim up [the runaway slave Huck Finn has been hiding], would you felt better than what you do now? No, says I,

I'd feel bad--I'd feel just the same way I do now. Well, then, says I,

what's the use you learning to do right when it's troublesome to do right

and ain't no trouble to do wrong, and the wages is just the same? I was

stuck. I couldn't answer that. So I reckoned I wouldn't bother no more

about it, but after this always do whichever come handiest at the time."

This is amazing! And hillarious, because Huck sees "done right" as giving up the slave he's been hiding. So he is completely oblivious to his noble act, viewing it as naughty disobedience. So, you're right. Twain allows Huck to be a normal kid, and he sacrifices nothing in burdening this character with a hefty ethical question. In fact the author has taken the opportunity to also make us laugh in the process.

Excellent writing!

by Mehman on Fri Jul 10, 2009 01:04 PM PDTDear Ari,

Excellent writing! I enjoyed the story much and I am on the verge of ordering your book: "The Mulla With No Legs..." from Amazon.

Desideratum

by Ari Siletz on Fri Jul 10, 2009 12:30 PM PDTConfession time

by IRANdokht on Fri Jul 10, 2009 09:19 AM PDTAri jan

I believe that my comments about the maturity of the young people in your stories might have come across as a criticism. I assure you that's not the case! Let me explain how these observations form in my head, maybe you'd see where I am coming from.

It might be a Virgo thing, it might not: I am my own worst critic. For example when I see a young toddler reciting the names of state capitals, a teenager playing classical music, a 12 year old winning the spelling bee contest, etc... my first thought is: I should have been a better mom!

So reading about a 7 year old analyzing someone's character, or a teenager outsmarting mob goons while I am sure, in their place, I would have been completely oblivious to all the details. To defend my own shortcomings (to myself), I start looking at other real life examples of people of that certain age. That's when in comparison your characters become superior to norm.

Maybe I associate with the character too much which pushes me to self-critique and that's because of the powerful writing and imagery. So my comments are definitely not criticism, but based on the effect the story has on me.

I thought about this all the way driving to work today and still wasn't able to adequately describe my intention for writing this comment! People who have your command on written words are blessed with the great gift of expression.

IRANdokht

Ari

by desideratum.anthropomorph... on Fri Jul 10, 2009 08:41 AM PDTThank you for yet another interesting read, which is incidentally, so poignant as a counterclaim to all the lies and misrepresentations of social justice in our land today under the same name as Ali’s legacy is taught.

If only the lessons of religions that could propel humanity to a more dignified life, rooted in myth or fact, could be taught as part of children’s literature, with no less urgency in our own land, the future might have some promises to make. Forgive the ignorance, but has your relevant work been accessible for Persian speaking kids and adolescents? Or does it sound like a plausible idea to you?

On the question of maturity, with all due respect, I think there are variations. Sometimes, the “perception” is “flatten onto a page” so smoothly that the reader’s eyes are fixated without any need to look where to ground what they perceive (this particular story is one good example in fact). But there are times when the reader is alerted to contrivance –though the act may certainly have been masked to the author herself at the time of creation.

Ari jaan

by ebi amirhosseini on Fri Jul 10, 2009 06:12 AM PDTyes,you're right.

Ebi aka Haaji

RedWine

by Ari Siletz on Fri Jul 10, 2009 02:29 AM PDTZulfaghar

by Ari Siletz on Fri Jul 10, 2009 03:40 AM PDTHistorically, I have always believed the "two-edged" theory, but mythologically I prefer the "double tipped" image. So much the better that such an implement would be useless for anything but pitting water melon sized olives.

Didn't know Zulfaghar was lost in 10th century. I bet someone got in big trouble afterwards. I wonder why carbon 14 dating can't determine the age of the big sword at Topkapi (the handle seems to have some wood or leather). Speaking of archeology, the ancient souk in Medina where Ali is supposed to have executed so many people can't be that far from where the souk is today. I wonder if the Saudis would allow a dig to see if there is any evidence of the alleged event? True or not, the tragedy is most dramatic and complicated in the moral and political dilemma it presented. If Medina had been betrayed by the Banu Qurayza at the battle of Uhud, a similarly tragic fate may have befallen the Muslims.

As for Ali's historic character, he came to mind strongly during the 2000 US elections. Ali is the earliest historic character I know that pulled an Al Gore. He withdrew his claim in the interest of unity. And he was much younger than Gore at the time. Quite mature of him (IRANdokht, hint).

Ebi

by Ari Siletz on Fri Jul 10, 2009 12:51 AM PDTIRANdokht

by Ari Siletz on Fri Jul 10, 2009 12:42 AM PDTAs for the maturity question, it seems to be an ongoing debate between us. For this round of debates I propose you think of the overly mature child narrator so common in (Western languages) literature as analogous to the distortions that occur in Cubist paintings. You may ask, do objects really look like that? To which the cubist may reply, "Why don't you ask a Classical Realist how he/she fits a three dimensional world onto a two dimensional canvas?" Likewise, all literature has to flatten perception onto a page. Some styles don't make a point of hiding that.

...

by Red Wine on Thu Jul 09, 2009 05:38 PM PDTدرود به شما ...

من زیاد داستان نمیخوانم، تقصیر خودم هم نیست،اینجوری عادت کردم و بیشتر هم تقصیر این بوده و هست که داستان نویسهای ما کم لطف هستند و در مورد موزوعاتی تکراری داستان مینویسند و اصلا جذاب نیستند !

سفارش شما را به من کردند و من هم داستان شما را خواندم و کم کم دارم امید وار میشوم که شاید نسلی جدید در بین داستان نویسهای ایرانی متولد شود.

منتظر کارهای آینده شما هستم.

سپاس گذارم .

Ms. Kaviani; It is

by varjavand on Thu Jul 09, 2009 05:01 PM PDTMs. Kaviani;

It is ironic, but understandable, that every piece in this site will eventually be turned into anti religion or anti IRI forum, that is fine with me because it is consistent with freedom of speech. I heard a story about this naïve peasant who went to a mosque to listen to the mullah’s sermon. He cried and cried from beginning to the end. They told him you are supposed to cry only when the mullah is reciting the noha and the story of suffering of Hussein and his family in the desert of Karbala. He said well, I don’t care what the Mullah is talking about, I only care about my beloved goat which I lost a few days ago, as he talks, his beard reminds me of my “lost goat” and my own suffering and that is what I am crying for.

Now the story of Zuhaghar, actually I read what is on display at Top Kopi museum is the sword of Prophet Muhammad, Zufaghar was lost in 10th century and no one knows its whereabouts. The reason sword is so important in Islam is that it represents the courage of the Muslim warriors, in the eraly days of Islam, and the merit of killing the non-believers in Islam. However, it is used today by Extremists to legitimize the acts of violence under the under the name of Islam. The story is told that Ali beheaded some 600 nonbelievers in one day with Zulfaghar, that is like 60 to 70 killing per hour!. I don’t care whether such stories are valid or not, what I am amazed by is that Muslims around the world have been inspired by such stories generation after generation and no one has dared to question their truthfulness.

Reza Varjavand

Ari jaan

by ebi amirhosseini on Thu Jul 09, 2009 04:33 PM PDTIt's always a great pleasure reading your writings.This one somehow reminded me of "Modir e Madreseh" by Aal Ahmad.

What happened to all good old traditions,like:

"People do not lie to an honest man".

Sepaas

Ebi aka Haaji

Ali's Sword

by Nazy Kaviani on Thu Jul 09, 2009 10:40 AM PDTIt was a great deal of fun reading this story again. This time also, when I came to the second grader's rationalizin of his earlier ommission of facts, I chuckled at his attempt to trivialize the deed with the "unauthorized sugar" arguement! Wickedly clever and funny!

I had a chance to see the Zulfaghar at Istanbul's Topkapi Museum a few year's back. It is a forbidding instrument, appearing heavy and menacing. I doubt any swords were light or easy to lift and use in that period. The stories I have heard about just what was accomplished with that sword are too macaber and gruesome to believe humanly possible. The size and assumed weight of that sword further defy any realistic application remotely close to the stories we have heard. Somehow, if I am to believe all the other things I have heard about Imam Ali, it is much easier to believe that your main character's demeanor in generosity, honesty, and kindness resemble what is said about Ali. I don't know about the sword business, though. Having seen those swords, I am more inclined to think that if true, Ali achieved all his accomplishments throuh diplomacy and not with a sword.

Take a look at this image showing the four swords of the four Caliphs, from top to bottom, Abu Bakr, Umar, Uthman, and Ali (the biggest), held in Topkapi:

//img168.imageshack.us/img168/8875/resim0173wj.jpg

Also said to be his swords:

//www.sword-buyers-guide.com/images/JP-Scimitar-tiles.jpg

//www.georgehernandez.com/h/xMartialArts/Media/Swords/scimitar.jpg

The following blog disputes the reported shape of Ali's sword. It contends that as with anything else we have heard through some hadith, something was lost in communication and the "double-edged sword" has somehow been changed to a "double-tipped sword," which everyone agrees would be something really hard to use in battle: //oasis77.blogfa.com/post-96.aspx

Thank you for provoking thought, Ari.

Thanks Ari

by IRANdokht on Thu Jul 09, 2009 09:58 AM PDTI read your wonderful story just before going to bed last night. There were many great points in your story that I thought of before dozing off. The narrative was smooth as usual which along with the right amount of character development keep the reader interested (hooked more like it).

It also brought up a couple of questions like were you really that mature at 7-8? :o)

Reading these stories that are so well-written, allows me to observe life from a completely different view and it's a thought provoking and enlightening experience. For example, I was 18 before I saw the inside of a butcher shop and was so disgusted by the sight and the smell, that I didn't spend any time looking at the picture frames nor thought to analyze anyone's character. I just got queasy and ran out of there.

I am not religious at all and Ali's zolfaghar has always bothered me deeply, but your story made me think about the positive influence that the myths, the beliefs and the lessons can have on people. You spoke of their faith without any bias and so calmly and fluently inserted it in your story that I didn't feel threatened by the whole idea (a rarity)...

Reading about the butcher's integrity,the norm of the shop keepers attitude back then and your mother's wise child-rearing expertise was a great experience.

Thank you for another gem.

IRANdokht

Thanks gitdoun

by Ari Siletz on Thu Jul 09, 2009 09:32 AM PDTactually it's not a criticism of Shiitism

by terry (not verified) on Thu Jul 09, 2009 07:40 AM PDTBecause if you read Baha'i History the 2 main figures of the Baha'i Faith were strong supporters of Shiitism...The Bab decaired that he was the Promised Quim on 23rd May 1844...And if you know any thing about the Bahai Religion you'd see that truthfulness and Honesty are #1 on the list of character attributes you may want to read this book from a Bahai Scholar about Shiite Islam //books.google.com/books?id=zot5IK1csp0C&dq=M...

also you may want to visit this website too for more Info..

//reference.bahai.org/en/t/nz/DB/

Peace!!

nice narrative

by gitdoun ver.2.0 on Thu Jul 09, 2009 06:24 AM PDT"Khomeini's refusal to compromise with what he thought to be evil eliminated the riddles of our conscience."

i think that is a faulty premise in which i believe is the cornerstone of your story/arguement.

terry

by Ari Siletz on Thu Jul 09, 2009 01:48 AM PDT